The Bury Psalter

A rare survivor from the medieval Abbey of St Edmund

This online display will take you on a journey through a beautiful, richly illuminated medieval book – the Bury Psalter. It dates from between 1399 and 1415 and was written for and used by the Abbey of St Edmund. It is one of only two books from the pre-Reformation Abbey to remain in the town of Bury St Edmunds.

It contains the Psalms of David, Litany of Saints, Prayers, songs for particular festival days, and hymns with musical notation. All of these are written in Latin. The pages are made of parchment (usually sheep, goat, or calf skin).

After the Abbey of St Edmund was dissolved in 1539 its possessions were confiscated and gifted or sold to private owners. This included its books. The Psalter ended up in the possession of James Cobbes and in 1706 his grandson, James Hervey, gave it to King Edward VI Grammar School. Today it is owned by the King Edward VI Grammar School Foundation Trust and cared for by Suffolk Archives along with other historic records from the school.

The Calendar

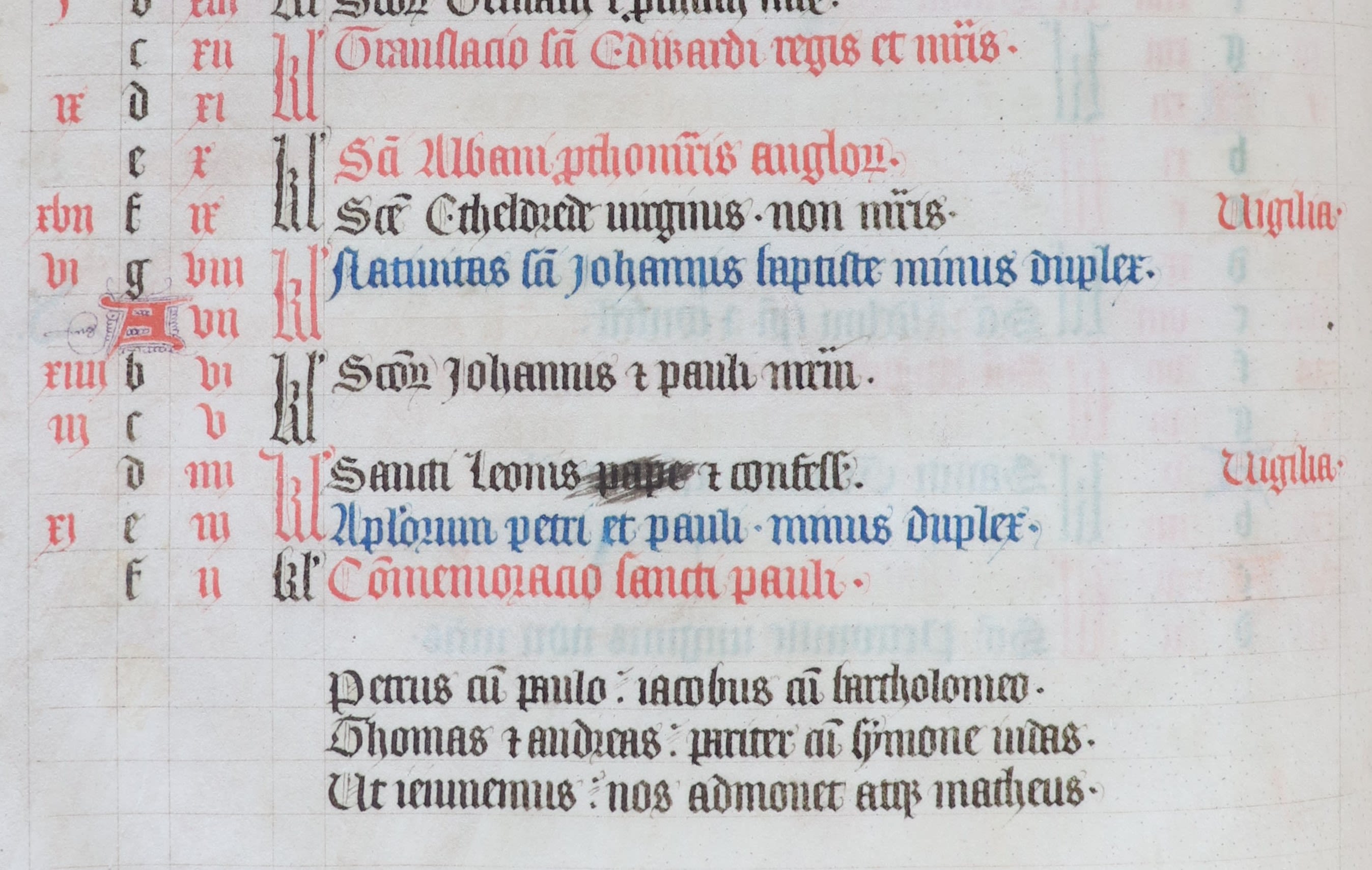

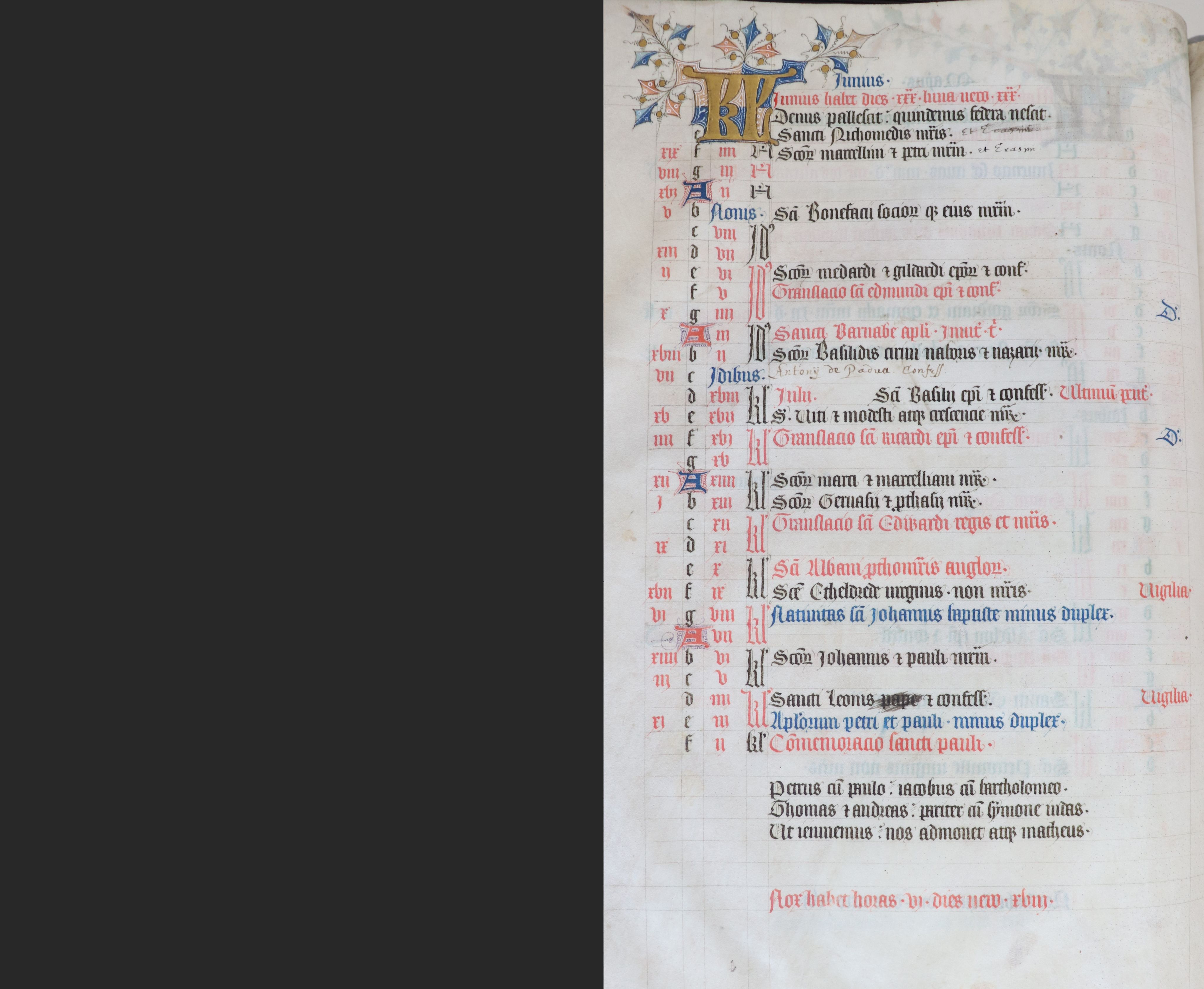

The manuscript begins with a calendar. There is a page for each month of the year, listing the religious festivals and saints’ days the monks were to observe.

The calendar was originally separate from the rest of the Psalter. There are two main clues that tell us this. Firstly, the calendar was originally bound onto seven bands, and the rest of the Psalter onto six. Secondly, the first page of the Psalms is damaged, suggesting that it was originally the first page of the whole book.

The narrower columns on the left of the calendar pages contain information that was used to calculate days which changed each year. The first column contains Roman numerals which were used to calculate when Easter would fall each year.

The second column contains a repeating pattern of the letters A-G; this was used to determine when Sundays would fall. Each year one of the letters would indicate a Sunday – so throughout an ‘A’ year, an ‘A’ day would always be a Sunday.

The third column relates to the Roman calendar, which was based on cycles of the moon. The first day of the Roman month was called ‘Kalendis’, which is where we get the word calendar. This is indicated by the large gold ‘KL’ at the beginning of the month. The fifth or seventh day of the month was ‘Nonis’, and ‘Idibus’ or ‘the Ides’ came eight days after ‘Nonis’. Both 'Nonis' and 'Idibus' can be seen in blue in the third column.

The days of the month were not numbered sequentially from 1 to 30 or 31. Instead, the days counted down to the next Kalendis, Nonis, or Idibus.

At the top of each calendar page you might find warnings about days which were considered to be bad luck, with advice against doing certain activities. These were known as ‘Egyptian days’, and there were 24 of them throughout the year. In June they were on the 10th and 16th – marked on this page by a blue ‘D’ on the right side of the page for those days. Another Latin term for these unlucky days was ‘dies mali’, which eventually became the word ‘dismal’.

The calendar was in use until at least the 1530s. Additions and changes were made to it as ideas changed. On this page the word ‘pape’, Latin for Pope, has been covered up, probably after the English church broke away from the Roman Catholic church under Henry VIII.

The Psalms

The most substantial part of the book is taken up with the Book of Psalms. This is a book of the Old Testament containing 150 religious songs. The Medieval belief was that they were composed by King David.

In the Bury Psalter nine of the Psalms begin with exquisitely decorated illuminated letters. Seven of these illuminations show King David, either depicting scenes from his life or showing him in scenes relating to the text.

Historians agree that King David probably lived around 1000 BCE. In the Biblical narrative he was a shepherd who gained fame by killing the giant Goliath and went on to become King of Israel.

The first illuminated initial is found in Psalm 1. King David is shown playing a harp inside a letter B which begins the word ‘Beatus’, meaning ‘blessed’. The Virgin Mary and baby Jesus look on from the margin.

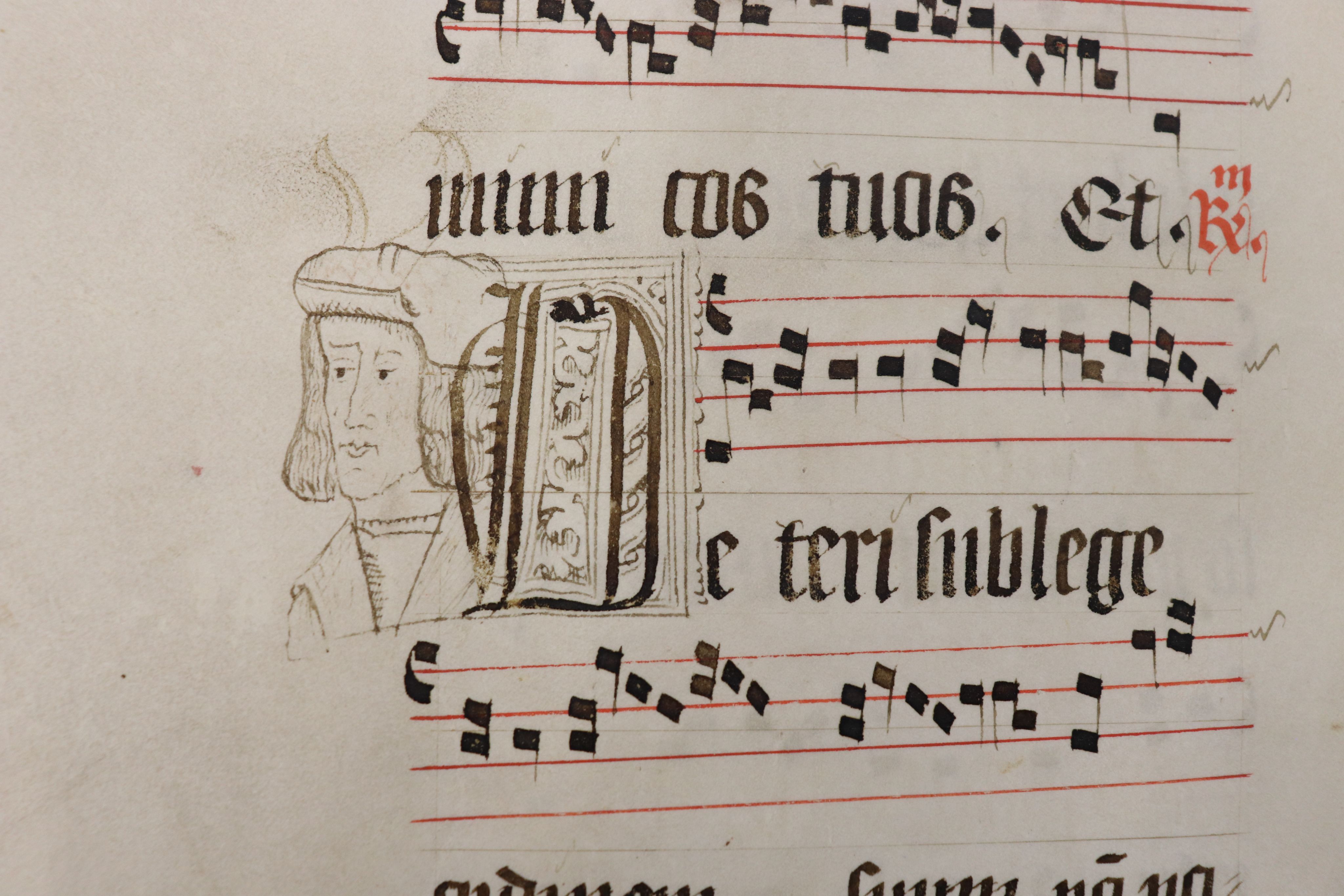

In Psalm 27 we see King David kneeling before an altar with green hangings, pointing to his eye. Above him we can just see the hand of God blessing him. He is inside the letter D, beginning the word ‘Dominus’, meaning ‘master’ or 'lord'. The opening words of this Psalm in English are ‘The Lord is the source of my light’. This may be why David is shown pointing to his eye and in communication with God.

If you look closely at the ‘U’ at in the bottom right corner of the illumination it is just possible to make out a royal coat of arms. Why the artist decided to put this here is a mystery – was it just for fun, or a subtle way of linking the king with this Psalm?

You can also see that the letter ‘s’ was missed out and has had to be squeezed in.

We next see David in royal robes, kneeling and pointing to his mouth. Above him is a figure representing God against a heavenly blue background. The first words of this Psalm in Latin are ‘Dixi custodiam’. The first line is translated as ‘I said, I will take heed to my ways, that I sin not with my tongue’.

The timeline of David’s life jumps back in the next image. Here we see him as a young man, before he was king, when he was a shepherd. In this image he is shown slaying the giant Goliath with his slingshot. The text of the Psalm contrasts a wicked man with a good one. The wicked man is struck down by God, while the good man prospers.

David is back to being a king again, this time shown with a medieval court jester or fool. The fool in the image has a dragon or wyvern wound around his head. They are inside a letter ‘D’ which begins the words ‘Dixit insipiens’ – ‘said the fool’. The text of the Psalm begins with a fool who believes there is no God.

In this image David is shown without his royal robes and crown, struggling in blue water. Above him is God, holding an orb representing earth in his left hand. They are inside a letter ‘S’, partly made up by a sea monster or dragon. The letter begins the words ‘Salvum me fac’ – ‘make me safe’. The Psalm is a prayer to God to save the speaker’s soul. Nude figures were often used to represent the soul, which is perhaps why David is shown here without his clothes.

The seventh illumination is the last time we see King David. Here he is singing and playing bells with a hammer, his harp beside him. He is inside a letter ‘E’ which begins the word ‘Exultate’. The Psalm is about singing merrily to God and making a cheerful noise with instruments.

We now move away from the figure of David, and glimpse how the Psalter would have been used. In this illumination a group of monks gather around a lectern to sing from a large book of music. The letter ‘C’ they are in begins the word ‘Cantate’ – ‘sing’.

In the final illumination from the Psalms we see a representation of the Holy Trinity – God the Father, God the Son, and above them a dove representing the Holy Spirit. A representation of the earth is held between the two figures. They are in a letter ‘D’ which begins the words ‘Dixit Dominus’ – ‘The Lord said’. The Psalm includes the words ‘Sit at my right hand, until I make your enemies your footstall', which explains the two devils chained beneath the feet of Jesus. If you look closely at the deep blue slices of colour around the inside edge of the D, the faint faces of cherubs can be made out.

The Litany

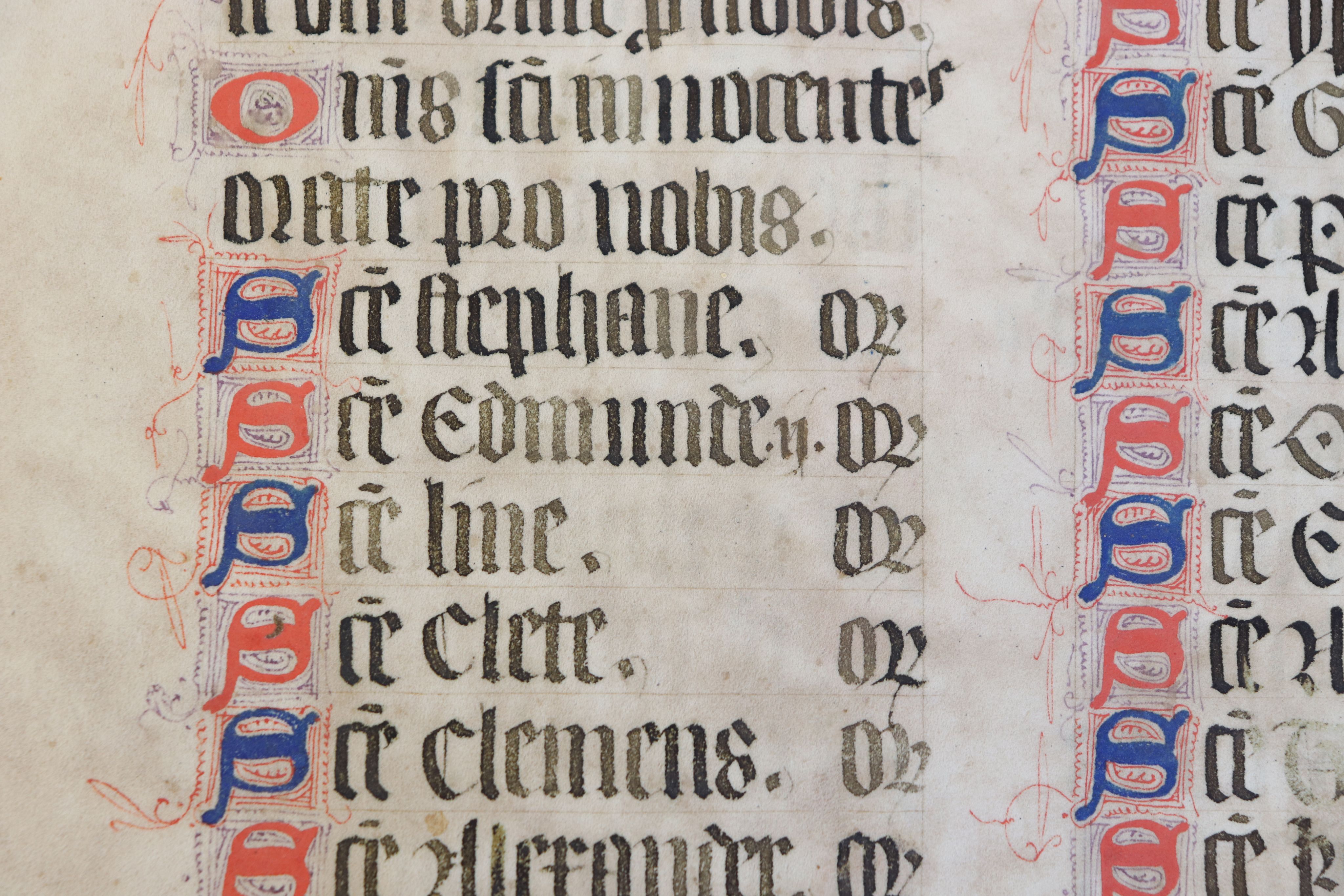

Like many other medieval Psalters, the Bury Psalter contains a Litany of Saints. This is a long prayer which calls on God, the Virgin Mary, angels, martyrs and saints. The list of names takes up several pages.

It is this litany which gives us some of the strongest evidence that the psalter was made for the Abbey of St Edmund.

The most important local saint, Saint Edmund, is listed as the most important martyr after Saint Stephen. Also listed are St Jurmin and St Botulph who are closely connected with the Abbey. Their bodies were moved there and their shrines richly decorated with silver in the time of Abbott Baldwin (1065-1097).

Hymns

In addition to the Psalms the Bury Psalter contains hymns. Hymns are also songs of praise to God but they do not appear in the text of the Bible as the Psalms do. Also unlike the Psalms in this volume, the hymns are shown with musical notation, indicating the melody to be sung.

The arrangement of hymns in the Bury Psalter is not found anywhere else. One short hymn about St Edmund may be unique to this book.

A legacy of the Abbey of St Edmund

The Bury Psalter would once have been part of a library of thousands of books at the medieval Abbey of St Edmund. This would have included other books for use in church services, religious books to be read to the monks while they ate their meals, and practical books such as medical volumes.

Today the surviving books are dispersed in libraries around the country and overseas. The Bury Psalter is an important reminder in our town of the lives of the monks who once lived here, the power and wealth of the Abbey, and the creativity that flourished within it.

Acknowledgements

This display has been produced by kind permission of the King Edward VI Grammar School Foundation Trust, and with assistance from Stephen Dart and Matthew Cooper.