Departures: Part One

History students from the University of Suffolk have explored stories of emigration from Suffolk as part of their course.

Suffolk's Jamestown Brides

The story of Ellen Borne and Margaret Dauson

In late summer and early autumn of 1621, 56 women voluntarily gave up everything they knew, left their homes and loved ones, and sailed across the world to the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia.

Known collectively as The Jamestown Brides, the women made the trip as part of a scheme run by The Virginia Company, who were seeking wives for their tobacco planters working out in the colony. The women travelled in a series of ships: the Marmaduke, the Warwick (which bought over the largest group of women), the Tiger, and the Sea Flower.

The women were found through word of mouth as well as via newspaper advertisements placed by The Virginia Company. Each bride was handpicked from the respondents and vetted for suitability to travel to Jamestown. To be selected, women had to come from respectable homes, have a good reputation, and be personally vouched for by a person of standing as having good character, moral worth, and practical skills that made them suitable marriage material.

All the women who travelled to Jamestown were volunteers. In return for their sacrifice, each woman was promised a free choice of who she would marry, a dowry of personal and home goods, and plot of land on which to raise her family.

But it was not just the women who stood to (theoretically) gain from their new lives in Jamestown. The Virginia Company were looking to turn around their fortunes and raise much needed capital to ease their financial struggles. Keen to retain skilled and successful male colonists, who would often leave the colony once they had made their fortune, The Virginia Company offered the brides for 150lbs of tobacco, to be paid to the company upon marriage. However, it is unlikely that the women being sold knew anything of this financial incentive.

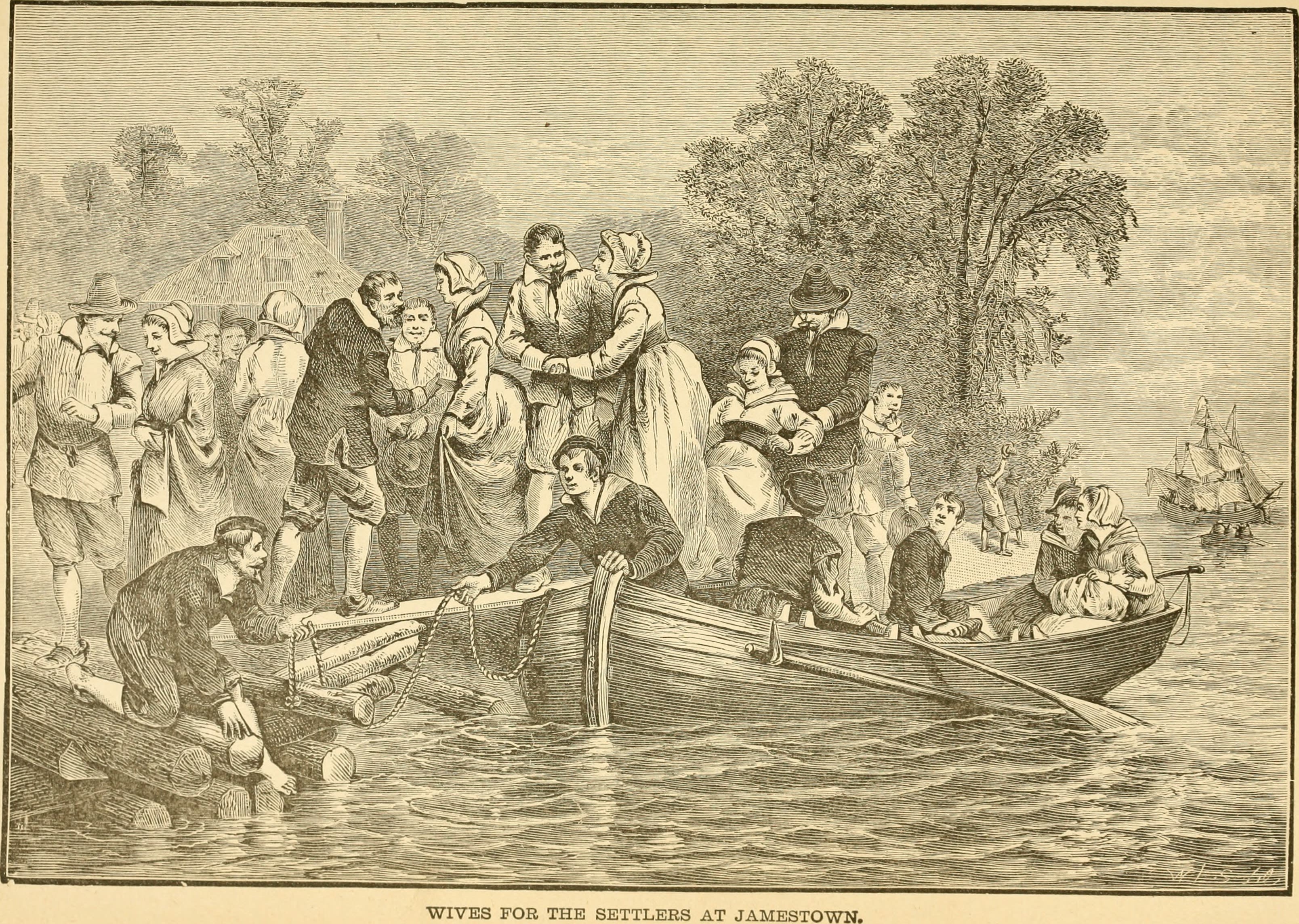

Alt: A nineteenth century illustration of the women arriving in Jamestown. There are three women in foreground, one of which looks thoroughly unimpressed, and a group of men in the background making no effort to hide the fact they are checking out the women!

Alt: A nineteenth century illustration of the women arriving in Jamestown. There are three women in foreground, one of which looks thoroughly unimpressed, and a group of men in the background making no effort to hide the fact they are checking out the women!

Ellen & Margaret - Suffolk's Jamestown Brides

Two of the women on board the Warwick were from Suffolk; Ellen Borne and Margaret Dauson. Both had been living and working in London before they left everything behind and set sail for Jamestown.

Ellen Borne

Ellen was from Eye and just 19 years old when she boarded the Warwick and left England for Jamestown. Ellen had been living in London and working for Drapers Company, a livery company of good reputation. Both her parents had died and as such it was her employer, Mr Hobson, who vouched for her, praising her work ethic and skills. Unfortunately, there is no available evidence that tells us who Ellen married or what happened to her once she reached Jamestown.

Margaret Dauson

Margaret was a little older than Ellen - 25 years old - when she joined Ellen and the other brides on the Warwick. Margaret was originally from Needham Market but had been living and working in the service of Mrs Elizabeth Stevenson, a leather seller's wife, in Southwark, London. As Mr Hobson did for Ellen, Mrs Stevenson vouched for her employee, praising her loyalty.

It is possible that once in Jamestown, Margaret married a man called Ezekiah Raughton. Records show that Ezekiah married a women called Margaret who arrived on the Warwick. However, Margaret Dauson was not the only Margaret who arrived on the Warick and as a surname isn't given, we cannot be sure which Margaret became Mrs Raughton.

"a sober and industrious maid skilful in many works"

- Mr Hobson's praise of Ellen Borne -

"a good and faithful servant"

- Mrs Elizabeth Stevenson's endorsement of Margaret Dauson -

The Journey to Jamestown

Ellen and Margaret's journey to Jamestown was long and arduous, even by the standards of the day. It took three full months to reach their destination, leaving in mid-September and arriving on 19th December 1621. They faced ferocious winds and turbulent seas that concerned even seasoned sailors experienced with making the crossing, all whilst living in cramped, unpleasant conditions on board the Warwick. Whilst all of the brides survived the crossing, it was far from the exciting, adventurous, and joyful crossing portrayed by popular culture at the time (see below, Impressions of the Jamestown Brides).

However, before leaving England, Ellen, Margaret and the other Jamestown Brides would have made a fascinating journey through London and round the South East coast of England to start their grand adventure.

In her book, The Jamestown Brides, author Jennifer Potter gives a vivid description of the sights and sounds of London as the women travelled along the Thames to Gravesend, Kent, to meet the Warwick.

Let's follow along their journey on this map from 1658. How many of these places do you know and recognise from Potter's descriptions? How much have they changed compared to today?

Ellen and Margaret's journey began at Billingsgate Quay, which is Old Billingsgate today. Potter says the gathering of the Jamestown Brides at the beginning of their journey "will have made an impressive site... amid the cacophony of ships and boats unloading passengers and goods from many parts of the world".

Next the women would go past Custom House, Wool Quay, and Galley Quay. Today, Custom House is in a completely different location, having been rebuilt in the nineteenth century. Wool and Galley Quay are now luxury apartments, but in 1621 they would have been bustling centres of international trade, lined with merchant's warehouses.

Just past Custom House was the Tower of London and Traitors gate, an imposing and dominating structure on the 1621 London landscape. Today, the Tower of London is a very popular heritage site!

Next came the areas of St Katharine's (where fellow Marmaduke Jamestown Bride, Jane Dier, came from) and Wapping. This is traditionally where pirates were hanged for their crimes. By the time of Ellen and Margaret's journey the hangings took place elsewhere, but the area was said to be unpleasant to live in, with filthy narrow alleys and small houses.

Onwards from Wapping to the areas of Ratcliff and Limehouse. Ratcliff is no longer used as a name for this area of London, but Limehouse remains, although it is now described as a former docklands area. At the time of Ellen and Margaret's journey to Jamestown, it was an area known for the production of ships and ship supplies and many residents had a connection with seafaring.

Our map ends here, where, as Potter describes, "the congested tenements give way to open country".

However, Ellen and Margaret continued on their journey, past the royal naval dockyard at Deptford, the royal palace at Greenwich, and onwards through a section of the river called Blackwall Reach (where the Blackwall Tunnel is located today); where they would have seen Bow Creek and the East Indian Company's shipyard.

These would have been small, isolated settlements surrounded by countryside, quite different from today where they are large areas of an even larger city.

Finally, the women would have continued towards the Thames Estuary, past small settlements of Woolwich, Erith, and Greenhithe, which all still exist today. The area was described as "wooded... with pleasant hamlets and homesteads". However it was busy, with "merchant ships to and from the port of London, and the men-of-war headed for the naval yards at Deptford in what was fast becoming one of the busiest waterways in the world".

Finally the women arrived at Gravesend to meet the Warwick. The journey to Jamestown had only just begun, and yet Ellen and Margaret, perhaps unknowingly, had already seen so much of England's connections with the wider world.

Next came a far more treacherous and less enjoyable part of their journey.

Ellen, Margaret, and the rest of the brides sailing on the Warwick left Gravesend in mid-September 1621. It is difficult to fully imagine what they must have been feeling as they stepped onto the ship that would take them away from everything they knew and off to a new life in Jamestown.

There was likely a lot of apprehension. Fear of the sea was widespread thanks to popular depictions of the dangers and disasters in popular street ballads and plays. It was customary to pray before a voyage and it is likely the women would have done so in the local church at Gravesend, before stepping on board the ship they were trusting to carry them safely across the Atlantic Ocean.

Little did they know that a particularly lengthy and difficult crossing awaited them.

A ship similar to the one illustrated here on this 1630 world map would be the women’s home for the next three months. For Ellen and Margaret life on board a ship would be a completely unfamiliar and very daunting prospect. It was a very masculine environment with widespread drunkenness, violence, and harsh discipline. The women would not have been particularly welcomed by the sailors, who would consider it bad luck to be accompanied by a woman at sea.

Whilst the women would have been housed together onboard, they would not have been given any preferential treatment and conditions would not have been pleasant. Space was at a premium, with the ship stuffed full of cargo, around 100 passengers (including the women), and 22 crew members.

Passengers were boarded in an area called the ‘tween deck – named literally as it was the area between the main deck of the ship and the lower hold. This area was also home to the ship's guns, as well as any perishable cargo to be used during the journey. The women were therefore unable to bring anything more than the clothes they were wearing and perhaps a small bag of personal belongings, if they were lucky. They really did leave everything behind.

Lack of space was made worse by a lack of natural light and ventilation. Passengers would have spent almost all of their time in the ‘tween deck; typically, passengers weren’t given much time on the deck of the ship, and only when weather was calm. All the daily activities of life were carried out in this tiny, cramped space with very little light, ventilation, and privacy.

If conditions were bad at the beginning of the voyage, they only worsened as the voyage went on. There was little in the way of sanitation or personal hygiene. The women had no way to wash clothing and would have worn the outfit they left home in for the whole journey. There was no way for them to wash themselves, their clothes, or deal with menstruation in a sanitary manner. Seasickness was common, as were infestations of lice and bed bugs. To compound the misery, the diet fed to passengers was often poor, no thanks to the limited cooking facilities for the ship's cook.

The crossing itself was notorious for bad weather and difficult sailing conditions. The storms that had battered ships making earlier crossings are said to have been so noteworthy that they inspired the opening scenes of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. To make matters worse, the Warwick was sailing across the North Atlantic during storm season and would have experienced some of the worst sailing conditions.

Jennifer Potter provides a vivid and compelling description of how this experience must have felt for Ellen and Margaret:

“Huddled in the ‘tween deck as storms raged, the women will have feared for their lives, wretched with seasickness and railing at their collective fate. Storms experienced at night were the worst… as they were tossed around in total darkness… sounds would appear terrifyingly loud: barked orders, cursing, thuds, waves crashing against the wooden hull, the cabin shuddering, wind roaring in the rigging, footsteps clomping on the deck above their heads.”

After three gruelling months, during which Ellen and Margaret no doubt questioned their decision to travel to Jamestown countless times, the Warwick reached North America. Despite all they had endured, thankfully all of the women have survived the journey. The end of such a brutal and terrifying experience must have bought great relief.

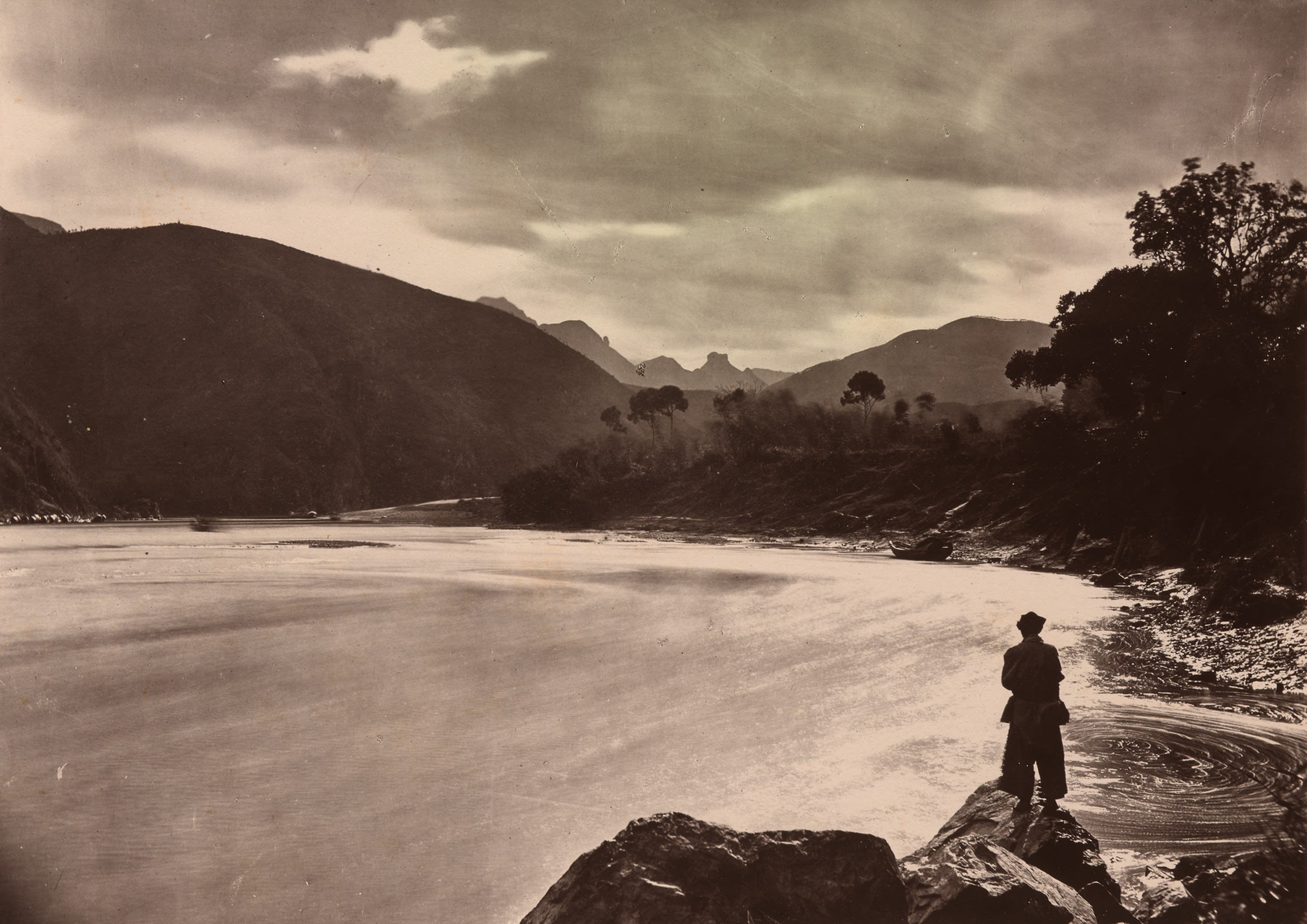

The final stage of the journey was to travel up the James River to reach Jamestown itself. Initially all they would have seen is thick vegetation on the sides of the river, with occasional signs of colonist activity. Once closer to Jamestown, more clearings in the dense forest will have become evident, and colonist activity more frequent. But still there was very little sign of this Jamestown, or James Cittie, they had been told about.

As they continued upriver, feelings of trepidation will have crept in. No doubt they will have spent many days and nights at sea wandering what their new home would be like. Will it live up to their expectations, hopes, and dreams?

Why did Ellen and Margaret go to Jamestown?

Leaving behind everything and everyone you know and making a dangerous journey across the world to a fledging colony in an unknown land is not a small undertaking, especially for a young, single woman in the seventeenth century. So why would Ellen and Margaret make such a brave decision to go on such an adventure?

It may seem obvious, given they are collectively called the Jamestown Brides, but the assurance of securing a marriage was likely a compelling factor for Ellen and Margaret. Whilst today marriage is not seen as an essential right of passage for women, in seventeenth century England marriage was essential for a woman if she was to have any social standing. Unmarried women were viewed with the utmost suspicion and could even be pursued by the authorities and detained to be "corrected" simply for being without a husband.

But why did Ellen and Margaret, who were both young, respectable girls, deem it necessary to travel across the world to find a husband, rather than seeking a match at home?

In short, it is likely that they felt their chances were better in Jamestown than in London, where they were both living. Finding a partner in early seventeenth century London was becoming increasingly difficult, due population growth, declining industries, and a squeeze on wages. Couples trying to save to marry and establish their own households took longer to gather the required funds, as did women and their families trying to collect a dowry for her marriage. Ellen and Margaret were at a particular disadvantage due to loss of one or both of their parents, which would make gathering a dowry and navigating the competitive and tricky London marriage market far more difficult without a family member to protect and guide them. They would also be competing with London-born women for the affections of London men, who usually chose their fellow natives over outsiders who had moved to the city. For some of the older Jamestown brides, such as those approaching 30 years old, they may have felt time was running out for them to secure a match at home.

As well as the chance of securing a marriage being higher in Jamestown, they may also have been influenced by the better terms and opportunities a marriage in the colony could provide. At home, it would be unlikely that any of the brides would be allowed to choose their own husband, especially those that were daughters of gentry or those of higher social standing. By going to Jamestown, the women were being offered a choice of partner. Not only that, but whereas at home marriage meant a women lost all her legal status and legal rights, with everything she had and anything she gains being the property of her husband upon marriage, these laws did not apply in the colonies. This allowed women who married in Jamestown all the benefits of marriage, but without the loss of her legal status as an individual, meaning she could have her own money, own her own property, and inherit assets that she would retain in her own name if she married again.

Without accounts from the women themselves to tell us why they made such a life changing decision, we cannot know for sure why they chose to go to Jamestown. However, given the importance of marriage in seventeenth century English society, that Jamestown offered Ellen and Margaret a greater chance to secure a marriage with more freedoms and rights than at home would be very difficult to resist.

"Economic hard times, losing one or both parents, migration to London and separation from kith and kin, the near impossibility of amassing a dowry fat enough to attract a good match, and the reluctance of London's young men to marry unendowed maidens when they had the choice of richer widows or London-born girls: all these undoubtedly contributed to the decision taken by some or all of the women to gamble their future on sailing to America."

- Jennifer Potter, author of

The Jamestown Brides: The Bartered Wives of the New World -

Did Ellen and Margaret go to Jamestown voluntarily?

As well as why they went to Jamestown, an important question to ask is whether Ellen and Margaret travelled to Jamestown completely voluntarily. Historians have debated this question with no clear agreement.

What do you think? Did Ellen and Margaret go to Jamestown voluntarily? Were they fully informed about what they were consenting to?

Do you think knowing any of the things that were kept from them would have changed their decision to go to Jamestown? Would they change your mind?

Ellen, Margaret, and the other Jamestown Brides did travel to Jamestown voluntarily after going through a vetting and vouching process and giving their consent; they were not abducted, stolen, or trafficked to Jamestown against their will. All the women faced external pressures, be it from society, the church, or their families that may have influenced them, but they still had the ability to chose whether to travel to Jamestown. However, women in the seventeenth century were trained to be obedient and had few options outside of securing a marriage, so would be less able to resist these external pressures.

On top of these external pressures, information was deliberately withheld from the women that may have influenced their decision. For example, they were unaware that they were being sold for a price, which also denied them one of the attractive benefits of marriage in Jamestown - a free choice of husband. Likewise, given the Virginia Company's reputation for ignoring negative reports about the colony and instead embarking on glossy PR campaigns, the women were unlikely to be aware of the reality of life in Jamestown. The company would not have seen fit to make them aware of the harsh conditions and the hard work required by colonists, as well as the risks to their safety, their health, and their slim likelihood of survival once they arrived. Whilst they went voluntarily, their decision to leave England was not a fully informed one.

Impressions of the Jamestown Brides

The departure of so many single young women to marry in an unknown land did not go unnoticed by those they left behind in England. Their brave decision to venture across the world in search of a new life not only caught the attention of those who saw them depart but also inspired the creation of tales and stories about their adventures, such as this street ballad. Published around 20-30 years after Ellen and Margaret left for Jamestown, The Maydens of Londons brave adventures talks of the bravery of the women who sailed on the Warwick to join those who had already gone to Jamestown on the Marmaduke, and encourages more women to follow.

For a closer look at some of the verses, keep scrolling!

"Peg, Nell, and Sisse, Kate, Doll, and Besse

Sue, Rachel, and sweet Sara

one, Prudence & Grace have took their place

with Debora, Jane, and Mary,

Fair Winifright, and Bridget bright,

sweet Rose and pretty Nany,

With Ursely neat and Alice complete

that had the love of many

All these brave Girls and others more

conducted by Apollo,

Have tane their leaves and are gone before

And their Loves will after follow."

This verse names many of the women who travelled on the Marmaduke, the first ship that took women to Jamestown. The women are described with using a number of soft, feminine adjectives to highlight their desirable virtues: "fair", "bright", "sweet", and "pretty". They are also described as "brave" for leaving their lives behind and heading to the colony.

"Then why should those that are behind

slink back and dare not venture

For you shall prove the Sea-men kind,

if once the ships you enter

You shall be fed with good strong fare

according to the season

Bisket salt-Beef, and English Beer

and Pork well boyld with Peason

And since that some are gone before

the rest with Joy may follow

To bear each other company

Conducted by Apollo."

This verse discusses the journey and suggests that the women will be well fed with hearty food and looked after by the sailors. Whilst all the women made it to Jamestown in relatively good health, as we have seen the reality of a journey would be very different than the author of this ballad suggests!

|

"When you come to the appointed place |

"Thine clothing then may serve your turn |

|---|---|

This verse paints an idyllic picture of life in the colony, suggesting that the weather is beautiful, there is an abundance of resources, much treasure to be found, and nothing in the world to worry about! Although the author still refers to the "brave Lasses" who have gone already, they suggest that they have an easy, carefree life, and that anyone thinking of following them has no reason to be fearful of life in Jamestown. As we have found out, the reality was very different.

"The Reason as I understand

why you go to that Nation,

Is to inhabit that fair Land

and make a new plantation

Where you shall have good ground enough,

for Planting and for Tilling

Which never shall be taken away,

so long as you there are living;

Then come brave lasses come away,

conducted by Apollo,

Although that you do go before,

your sweet-hearts they will follow."

In this verse, the author once again highlights the bravery of the Jamestown Brides and gives an idea as to what those back home think motivated the women to travel to the colony. They suggest that the women are part of efforts to establish and maintain a prosperous and successful colony, supported by tobacco plantations. However, the fact that the women were recruited and sold to make profit for the struggling Virginia Company does not, unsurprisingly, make it into the ballad.

Whilst the ballad does contain a number of inaccuracies, such as suggesting that the women already have "sweethearts" that will follow them to the colony, it does give us some insight into how those back home perceived the Jamestown Brides. It is clear that although the ballad paints a far more romantic and thrilling picture of their experience than the reality, the bravery of the women to give up everything and travel to the colony was recognised even at the time.

Suffolk, England,

to

Fuh-kien, China

Margaret Emma Barber's Christian Mission

Margaret Emma Barber

Born in Peasenhall in 1866, Margaret Emma Barber lived 64 years until her death in Fuhkien, China. She travelled there as a 29 year old, unmarried, Victorian woman, to become a Christian missionary. The fact that she remained unmarried her entire life, and that she rarely returned to England, suggests she found herself much more comfortable in China than England, making her a particularly interesting candidate for historical study.

This article will trace Margaret's life - records permitting - with particular focus on her youth and early years in China, in order to understand what might have motivated a young Victorian woman to make such a departure from the expectations of her class and gender, choosing to depart for China, instead.

Early Life

The daughter of Louis and Martha Barber, Margaret spent the first decade of her life growing up in Peasenhall surrounded by her six siblings (two brothers, four sisters!). Her father at this time was a wheelwright, however, after the family moved to Norwich in the late 1870s, Louis established a coach building business with Margaret's brother, Harry. It is likely that the income from this business, which was employing 'one boy and three men' in the 1881 census, is what allowed Margaret to afford the training she undertook in her twenties before she became a missionary.

The Barber family's move to Norwich saw them living in St Martin Lane, which also housed the local evangelical parish church, St Martin at Oak. The family would come to attend join its congregation.

St Martin's Lane, 59, 1st November 1938.

George Plunkett's Photographs of Old Norwich

Though we do not know for certain which house Margaret lived in, a letter she wrote in 1907 has her return address as "59 Martin's, Norwich". It seems likely this was her childhood home, as the large gate door (pictured right) would be of use to her father's coach building business.

St Martin's Lane, 49 to 55, 10th April 1936.

George Plunkett's Photographs of Old Norwich

These additional pictures depict Margaret's childhood street, only 29 years after her last known visit there.

St Martin's Lane, 61 to 69, 10th April 1936.

George Plunkett's Photographs of Old Norwich

St Martin's Lane, 47 and Quakers Lane East Side, 5th October 1936.

George Plunkett's Photographs of Old Norwich

Understanding 19th Century Evangelicalism

In order to understand Margaret, and her decision to become a missionary, we must understand the world she lived in, the views and ideas that swirled around her, and how these factors came to inform her view of the world. For this, we will dip our toes into English Protestantism of the 19th century, taking a look at Evangelicalism, evangelism, and the difference between the two.

First, lets distinguish between evangelism and evangelicalism:

Evangelism is the act of sharing the Bible and the teachings of Jesus Christ with the intent of converting non-believers to Christianity. In theory, all strands of Christianity seek to evangelise, as Christianity is a 'missionary religion', a type of religion that seeks to convert others. However, in practice, different strands of Christianity place greater or lesser emphasis on this directive.

Evangelicalism is an interdenominational movement within Protestantism in which evangelization is one of the core tenets. Evangelicalism places utmost importance on the idea of missionaries - members of the Church who would travel to their 'mission field' in order to convert people and grow the Christian faith.

David Bebbington, a historian known for his study of Evangelicalism, writes of four main qualities of Evangelicalism; these have come to be known as the Bebbington quadrilateral:

"Conversionism, the belief that lives need to be changed; activism, the expression of the gospel in effort; biblicism, a particular regard for the Bible; and what may be called crucicentrism, a stress on the sacrifice of Christ on the cross. Together they form a quadrilateral of priorities that is the basis of Evangelicalism."

Interesting to note is the etymology of 'evangelicalism;, which comes from the root word 'evangel' meaning 'bringing good news' in Ancient Greek.

Colonialism and Evangelism

Margaret's life and work as a missionary must also be placed in the context of Britain's Empire and colonial projects. Missionaries and missionary societies played a complex, multi-faceted role in this regard, a fact we shall explore briefly here.

Whilst merchants were often the source of the first contacts between Europe and Asia, it was often the literary work of missionaries that formed Britain's impressions of foreign countries. Missionaries, both those 'in the field' and those who had retired home, were prolific writers; "diaries, reports, let-

ters, memoirs, histories, ethnographies, novels, children's books, translations, grammars, and many more kinds of texts spilled from their pens.", writes historian Anna Johnston.

Far from being bystanders in the colonial project, missionaries were intimately involved in what is called 'the production of knowledge'. In other words, the creation of textual - and non-textual - works that developed public and elite opinion. This production was done with specific goals in mind, such as the expansion of evangelism & colonial territory, or the erasure of indigenous (and therefore heathen) practices and culture.

To illustrate this, Anna Johnston quotes Reverend Robert Burns, who spoke at the London Missionary Society in 1834:

"Long did the Christian world remain very imperfectly informed of the real nature and effects of heathenism in regard to its blinded votaries. Misled by the theories of some over-refined speculators, and relying implicitly on the statements of certain interested voyagers or historians, we dreamed of the pagan tribes as pure in their manners, and refined in their enjoyments ... It was not til the Christian world was awakened from its lethargy... that our mistakes regarding the actual state of man were rectified, and facts and illustrations, hitherto neglected, brought forward to view in all their revolting reality. A spirit of inquiry into the state of the world at large has been cherished. More accurate accounts of its real condition have been obtained."

In other words, Burns argues that the popular imperial imagination of India and China as towering civilisations of the ancient world, rich in their beauty, has been shown to be false by the writings of missionaries. Instead, the Asian and African continents are inhabited by backwards heathens living in "revolting reality".

The Significance for Margaret

St Martin at Oak was an evangelical church, and the bishop of Norwich at the time, John Pelham, was also an evangelist. For these reasons, it is likely that it was during Margaret's formative teen years that her desire to become a missionary formed, and potentially solidified, under the influence of the evangelicalism that surrounded her. That being said, it is possible that Margaret's convictions came to her much earlier; Watchman Nee, a Chinese Christian who knew Margaret intimately for many years, recalled a conversation between the two of them several years after her death:

A few months before Miss Barber died, I went to see her and spoke with her for a long time. I asked her why the Lord had been so gracious to her. She answered, "I do not know. I only know that I have always been hungry and I have always been eating. Since I was nine, I have always been hungry; I have never been content before the Lord for these many years. I might have received grace and revelation yesterday, but today I say to God, `You have more, and I want more. I want more all the time.' I am forever hungry and yet at the same time forever satisfied."

Worship and services at St Martin would have naturally focused on Bebbington's quadrilateral, however it is the aspects of conversionism, activism, and biblicism, that seem to have affected Margaret the most. Her missionary work in China combined her beliefs in conversionism and activism, and her writings, as well as second-hand accounts of her character, show an exceptionally detailed knowledge of scripture.

For permission for Images from the George Plunkett site see here

The Church Missionary Society

'Mission', the act of sending missionaries abroad, was not an individual task in the 19th century. Instead, missionaries were almost always part of an institution that organised and corresponded with missionaries in many different places. The Church Missionary Society (CMS) was the organisation that Margaret joined, probably in the mid-1890s, by which point, from its founding in 1799, the CMS had grown into one of the largest missionary organisations in the world.

Andrew Atherstone records that:

In 1906 the society had an annual income of about £300,000 (equivalent to about £30 million today). It employed 975 missionaries, 8,850 native agents, and operated 37 theological and training colleges, 92 boarding schools, 12 industrial institutions, 2,400 elementary schools, 40 hospitals, 73 dispensaries, 21 leprosaria, 6 homes for the blind, 18 orphanages, 6 other homes and refuges, and 17 presses and publishing offices. At the high-point of the British Empire, the CMS was, as Peter Williams... observes, itself ‘a mini-empire’.

Training in Stoke Newington, London

In the years before her mission to China, Margaret trained at 'The Willows', an estate in Stoke Newington that trained women missionaries. It was one of three women's training schools run by the Church Missionary Society during this period, the other two being The Highbury and The Olives in South Hampstead. The training was extensive, and the expense costly. For £55 per year of study, 'probationers' - missionaries in training - were taught a range of subjects:

Ian Welch, Women’s Work for Women: Women Missionaries in 19th Century China, Eighth Women in Asia Conference, (Sydney: University of Technology, 2005).

Ian Welch, Women’s Work for Women: Women Missionaries in 19th Century China, Eighth Women in Asia Conference, (Sydney: University of Technology, 2005).

Fuzhou, China

A map of Fuh-Kien (now Fujian) from the Church Missionary Society.

(T. McClelland, For Christ in Fuh-Kien, (London: Church Missionary Society, 1904).

When Margaret arrived in Fuh-Chow on the 6th of March 1896, she had spent the last five days travelling 680 miles by steamboat from Hong Kong. 'Lovingly welcomed' by a number of women missionaries, Margaret found herself amongst her peers from the CMS, but also a number of women working for the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society, who placed particular focus on converting women.

Highlighted in red is the River Min, which gave missionaries the opportunity to establish footholds much further into the Fuh-Kien. Travel through a region lacking paved roads and railways might have initially appeared difficult, however Fuh-Kien has a long history of maritime transport, which missionaries (and photographers, as you shall see) took advantage of this to navigate the region.

Observe the circles with crucifixes attached; these denote CMS stations.

Finally in China

Three days after her arrival in Fuhchow, on the 6th of March 1896, Margaret wrote back to London, confirming and detailing her safe arrival. In her letter, Margaret expresses her excitement at beginning her study of Chinese, as well as her joy at having finally reached Fuhchow. On the 21st November she reiterated this feeling, writing,

"Blessed with good health, and allowed to live in this land, a joy to which I looked forward for ten years, enjoying the language and loving the people, I can only say, “My cup runnerth over.” Hallelujah!"

Pictured below is Margaret along with the growing number of women missionaries in Fuhkien. The caption and image are both taken from the Church Missionary Gleaner, a journal published by the CMS.

'Women Workers in Fuh-Kien', The Church Missionary Gleaner, Volume 24, Issue 279, 1897. In the back row, fifth from our left is Margaret Emma Barber.

'Women Workers in Fuh-Kien', The Church Missionary Gleaner, Volume 24, Issue 279, 1897. In the back row, fifth from our left is Margaret Emma Barber.

“Starting from our left the women standing at the back of the group are Miss Garnett (a Canadian worker), Miss J. E. Clark, Miss Goldie, Miss Little, Miss Barber, Miss Bushell (F. E. S.), and Miss Oatway. Those sitting in the middle are Miss J. C. Clark, Miss Boileau, Miss Harrison, Miss Wolfe, Miss Annie Wolfe, and Miss Leybourn. Miss Clemson, Miss Brooks, Miss Andrews, and Miss Oxley sit upon the ground in front.”

Margaret Emma Barber, between 1896 and 1897.

Margaret Emma Barber, between 1896 and 1897.

The Work in China

Whilst it is very difficult to ascertain exactly what work Margaret did in Fuhchow, contemporaneous internal histories of the CMS, as well as further accounts from Watchman Nee, give us an idea.

Reverend T. McClelland's For Christ in Fuh-Kien describes three categories of women's work: (1) Training of Bible-women; (2) station classes; (3) girls' boarding schools.

(1) The training of bible-women involved educating the wives of converted Chinese men in basic scripture, with the hope that they would then be able to evangelise to others. This process also gave missionaries the ability to sharpen their own language skills, as well as have women who could act as translators for them.

(2) Station classes were stations opened for the purposes of educating Chinese women on the gospel. Chinese women would stay at these stations with the women missionary for three months, their room and board paid for by the Society.

(3) McClelland writes of the girls' boarding schools "In the boarding-school for the children of Native Christians, the teaching is carried on in the native language. The girls are instructed in the Bible... They are taught a little geography, arithmetic, history, and singing; they learn to read and write in the Chinese character, and in the Romanized colloquial, and also how to make their own clothes and shoes, and to do all kinds of household work. But the chief aim is that they may become true believers in and followers of the Lord Jesus, and, in time, missionaries to their own people."

It is likely that Margaret engaged in all of these activities, and certainly more; of particular note is Watchman Nee's account travelling "every Saturday... to listen to Miss Margaret Barber's preaching." This suggests that women missionaries often took on work that would be reserved for men back in England, a possible reason for her remaining in China.

A Day in Fuh-Chow, by Margaret Emma Barber

The following text reproduces a letter written by Margaret to the Church Missionary Society in London. They subsequently published the letter in the journal CMS Awake!. This was a common feature of many missionary societies, whereby donations were sought and maintained from wealthy benefactors by providing them with attractive 'knowledge' about the mission-fields. Given this, as well as the style of Margaret's writing, it is likely she knew this may be published at home, so we must treat this source cautiously when trying to ascertain Margaret's experience of China. For instance, one can see Margaret's pandering to 'English sensibilities' throughout this text, and we should be mindful also that this, too, is a contribution to missionaries' production of knowledge.

Additionally, I have included photographs of the period from Burton Beers' China in Old Photographs. Due to the limitations of photography in China in this period, these should not be seen as completely representative of Margaret's world, particularly as not all of them are from Fuhchow.

This is as far as my investigation has taken me into Margaret's unique and fascinating travels and life. The research process has meant I have become quite attached to her, particularly her vivid and evocative prose. With that said, I shall let her finally speak for herself.

Would you care to imagine yourselves living here, and about to visit a poor heathen woman in her little cottage? If so, let us start! It is very hot, so we must put on sun-hats and take our white umbrellas! As we cannot speak Chinese, we will wait for Mrs. Sieh, the English-speaking wife of our Native catechist. Here she comes with her clean dress and her flower-decked hair—no hat and no umbrella, for she does not mind the sun. How bright she seems and how sweet she looks! We must take this turning to the right, and go down this narrow lane. How dirty it is! How bad are the smells, and how black the pigs which we see in all directions (all the Chinese pigs I have ever seen are black). Also don’t you feel that you will never get accustomed to being stared at by every passer-by?

Presently we arrive at our destination, and knock at what looks like a wooden fence. A woman comes, very poorly dressed, with a baby in her arms, and we step inside. The door is locked after us, so we shall be quiet. That is unusual and very nice. We cross the little yard and seat ourselves on one of the benches in the little room. The floor is of earth, and the furniture consists of two benches, one old table, and incense sticks in jars for burning before gods, of which there are plenty on the wall. How nice it is to be able to pray and listen as Mrs. Sieh tells I Sung the story of a Saviour’s love. How one longs for God Himself to open the hearts of these poor ignorant women! Before we leave we have prayer together—prayer in a heathen home, with signs of idolatry on every side. How grand to know we plead the All-Prevailing Name!

Before leaving I discover that I Sung has three children, but she has only two in the house with her. “Where is the other one?” I ask. “Oh!” says the mother, “she is a girl, so I gave her away.” Not only that, but she seemed so unconcerned about it that I felt a new meaning was lighting up those words of Him Who loves us so tenderly: “Can a woman forget her child…yet will not I forget thee.” Poor, ignorant mother, do pray for her and her children. There is a nice little incident about this woman which I must tell you. She wanted to come to service in the little chapel attached to the school, but she had no clothes, only rags, and no earrings. What was to be done? The dear girls in this school heard of it, and subscribed, some one cash, and some more, and bought I Sung an jacket and trousers, and gave her the surplus money to get her earrings out of pawn. What a nice example for us! Of course there was great excitement when I Sung appeared in her new suit the following Sunday, but only one girl was unable to suppress her pleasure and curiosity. They had all been warned not to stare at their friend and make her uncomfortable.

It is so lovely for these girls to be here. They get such splendid teaching, and are surrounded with such holy influences. Most of them, when they leave this school, are married to Native catechists or pastors, and thus a life of usefulness is before them. Miss Bushell, the Principal of the school, is dearly loved by all her girls. Her sweet, holy influence must tell upon all with whom she comes in contact. One day I heard one of the older girls talking so earnestly to an old woman, and found she was explaining John iii. 16. The woman was a Heathen, who had come in from curiosity. One just longed for her to understand that it was for her that God gave His Son.

I must tell you of another visit I paid; this time to a heathen day-school. It is too far to walk, and there are no conveyances except these funny little houses swung between two bamboo poles. It really is very cosy inside the chair. My chair is painted green—vivid green—because the Chinese like bright colours, and I have windows in it, so that I do not feel as prisoner! Presently we start. The coolies want to go their way, avoiding the hilly places, but taking us by paddy-fields. They have to give in, however, and go the right way, avoiding thus the unpleasant odours of paddy. How lovely the country is, and how nice the fields look, clothed in their bright green! Our coolies are so glad when we get out and walk. After about an hour’s journey, perhaps hardly so long, we reach the village. Perhaps you may picture (as I used to do) a sweet little English-looking village, with its greensward and pretty gardens, and merry children; but Chinese villages are not like that. This one is a typical one. How shall I describe it? Generally there is one narrow, dirty street full of children, almost without any dress, barking dogs, staring men and women, and the usual number of grunting black pigs. We do not go through the street this time, however, but up a narrow passage, and a turn to the right leads us into a courtyard full of puddles and naked children, and after finding a fairly clean place for our chairs we reach the school. Here it is a very dirty iangdong (or room almost open to the sky); in it a table, four forms, six children, the teacher, and the usual number of hens, together with a friendly visitor, who now and then picks up a morsel, viz. the indispensable black pig. No sooner are we seated than the neighbours flock in and dozens of children. All want to see the foreigner.

I do with I could paint the scene. Do you see that man walking round in search of something? He is one of the coolies. In his search he discovers the teapot, and takes a good drink. Presently, failing to find what he wants he asks for it, and is presented with a pipe. How does he light it? He has no matches, no fire, and no other light to light it by, and if you watch you see him using flint and tinder, such as our forefathers used in this country years ago. It does seem such a funny way to get a light. The coolie is very liberal with his pipe, for I see him handing it to all the other coolies in turn. This woman sitting by me is a decided trial to the examiner, Miss Bushell, for she yells at the top of her voice when any newcomer appears, but as she is deaf and dumb, we must not mind the curious sounds she is making. I see and feel, too, that the children are touching my hair and dress, and sitting as close to me as they can, making room for each other in a most ingenious way. It is quite funny to be on view in this fashion. Here is a sweet little girl about ten years old. Let us hear her repeat, “Jesus loves me, this I know”; she says it so nicely, but when I question her I find she knows very little about the precious Saviour “Who died, Heaven’s gate to open wide.” The Chinese children can get things off by heart in a most surprising way, but it never dawns on them to think about what they learn. Miss Bushell says Chinese children can never be taught to love knowledge for its own sake—they always want to be paid to come to school. This is why only six are here to-day. That little girl on our right looks so ashamed and is listening so quietly to what Miss Bushell is saying. What is it all about? She does not know her lessons well, and Miss Bushell has asked the reason, and has been told that her little pupil makes idol-paper all day long, and has no time for school. Poor little girl! She does not want to make the idol-paper, but she has to work—her parents make her do it. Will you pray for her, dear friends? She has promised to ask God to make a way for her to earn some money apart from idol-paper making.

As we make our way home in the cool evening, we notice several very curious things—curious to my eyes at least. Here is a buffalo with only his head out of the water, evidently enjoying the coolness of a slimy pond. Then we meet a gaily-dressed Chinaman, in blue and scarlet, with a servant behind him, and a chair in attendance. He looks very lordly, but he is only a poor teacher, earning six dollars a month, who has lately got a degree and is visiting his friends, having hired the servant and the chair to impress them with a sense of his greatness. There are some men watering their little plots. What curious watering-pots they have!—all of wood, with a spout like a flute, out of which the water comes in fountain-like sprays. Quite as effectual, this little flute-like arrangement is, as our more elaborate way of doing things in England. What a number of people we see carrying their suppers home on a string. It has one advantage—one can see what they are going to eat. We see black, crab-like creatures, goats’ flesh, dried vegetables, green-looking cakes, fish like young codfish, and a great many very unwholesome-looking dainties, whose names I am quite ignorant of. I hope I shall remain quite as ignorant of the taste of them. It is getting dark, so we get into our chairs. There is a Christian Endeavour meeting at seven. An English-speaking Chinaman will give the address. Afterwards he stays to supper with us, and tells us about great blessing in a district in which he has lately been. He also tells us that, rather than work on Sundays, he goes to his office at 6 a.m. and stays there till nine o’clock, and then enjoys what he calls his Sunday rest. He does not realize that we know he preaches twice every Sunday, and visits besides. Oh, that God would raise up many such men to testify for Him in this dark land! Pray for this, dear friends, and for all who are here.

With loving Christian greetings,

I am yours in Christ’s glad service,

Margaret Barber.

Burton F. Beers, China in Old Photographs 1860-1910, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1978).

Burton F. Beers, China in Old Photographs 1860-1910, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1978).

Burton F. Beers, China in Old Photographs 1860-1910, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1978).

Burton F. Beers, China in Old Photographs 1860-1910, (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1978).

John Winthrop - A Puritan Founder of New England from Old Suffolk

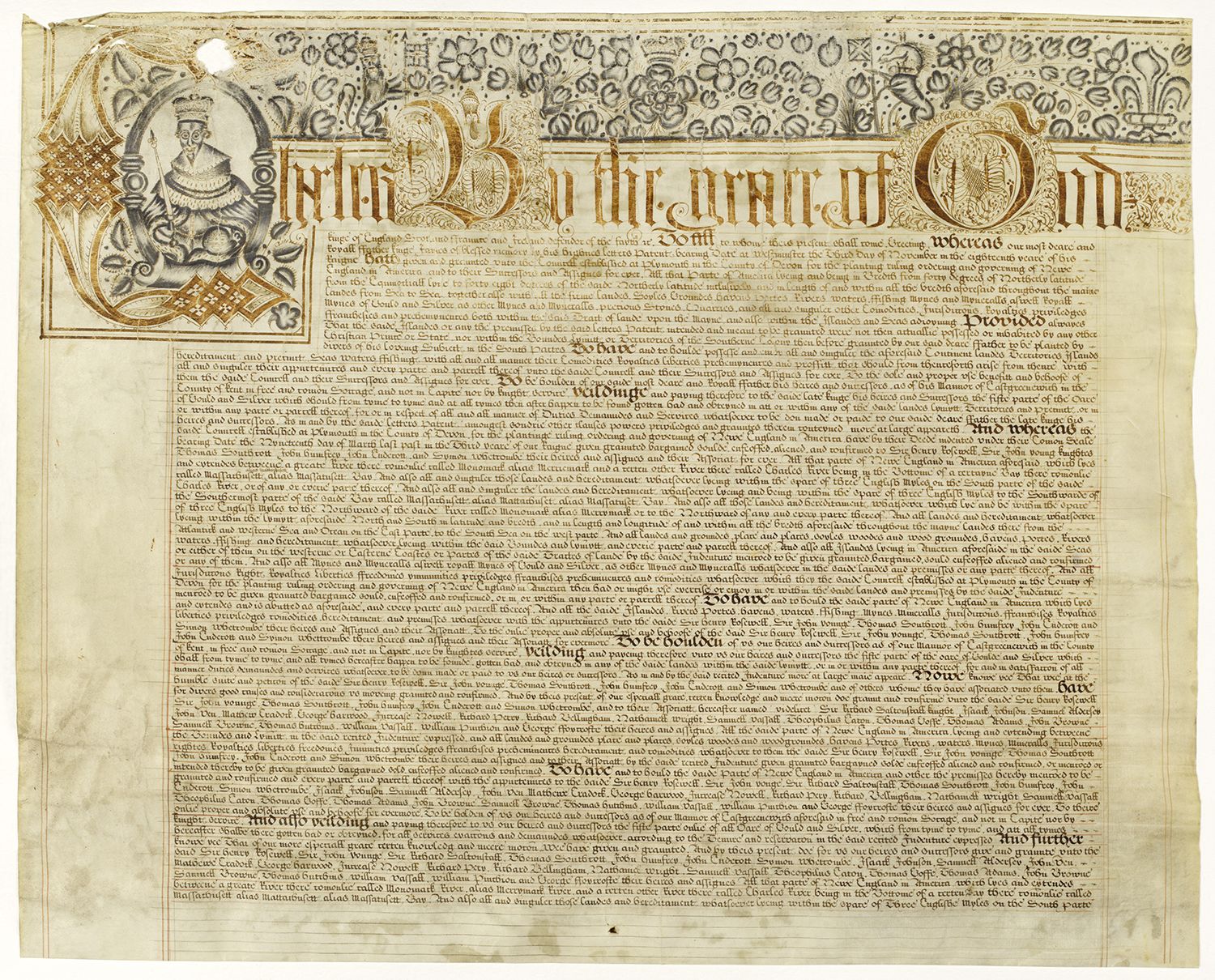

Left: The 1629 Charter of Massachusetts Bay. John Winthrop brought this manuscript from Old England to the New World on the Arbella in 1630 and the Puritans founded the city of Boston under this charter. (This charter is displayed in the Treasure Gallery of the Commonwealth Museum in Boston, Massachusetts.)

Puritan Emigration from Suffolk

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Puritan movement gained rapid support in Suffolk and East Anglia. This made Suffolk a Puritan stronghold during the seventeenth century, reinforced by East Anglia's "deeply ingrained" hostility for the Church of England.

However, the Puritans had always been an "embattled minority" in England, and during the seventeenth century, their influence began to wane in the regions where they had succeeded in shaping the religious culture. They even became vulnerable to "royal and ecclesiastical encroachment" on their religious liberties and beliefs.

The Puritans had hoped to use Parliament to protest against royal policies and redress these grievances. However, King Charles I's decision to dissolve Parliament on 10 March 1629 not only destroyed those hopes but also convinced the Puritans that England was no longer safe for them to live, let alone freely practice their religious beliefs.

Therefore, to escape from religious persecution, approximately 20-21,000 English Puritans emigrated to New England in America from 1629 to 1642, during the peak of the Great Puritan Migration, which began with the Pilgrims' establishment of Plymouth Colony in 1620.

A notable Puritan emigrant from Old Suffolk who was increasingly frustrated by the Church of England and Charles I's anti-Puritan policies was John Winthrop, who had a crucial role in leading the first large wave of Puritan emigrants to New England in 1630 and influencing other Puritans to emigrate from Old Suffolk during the 1630s and 1640s.

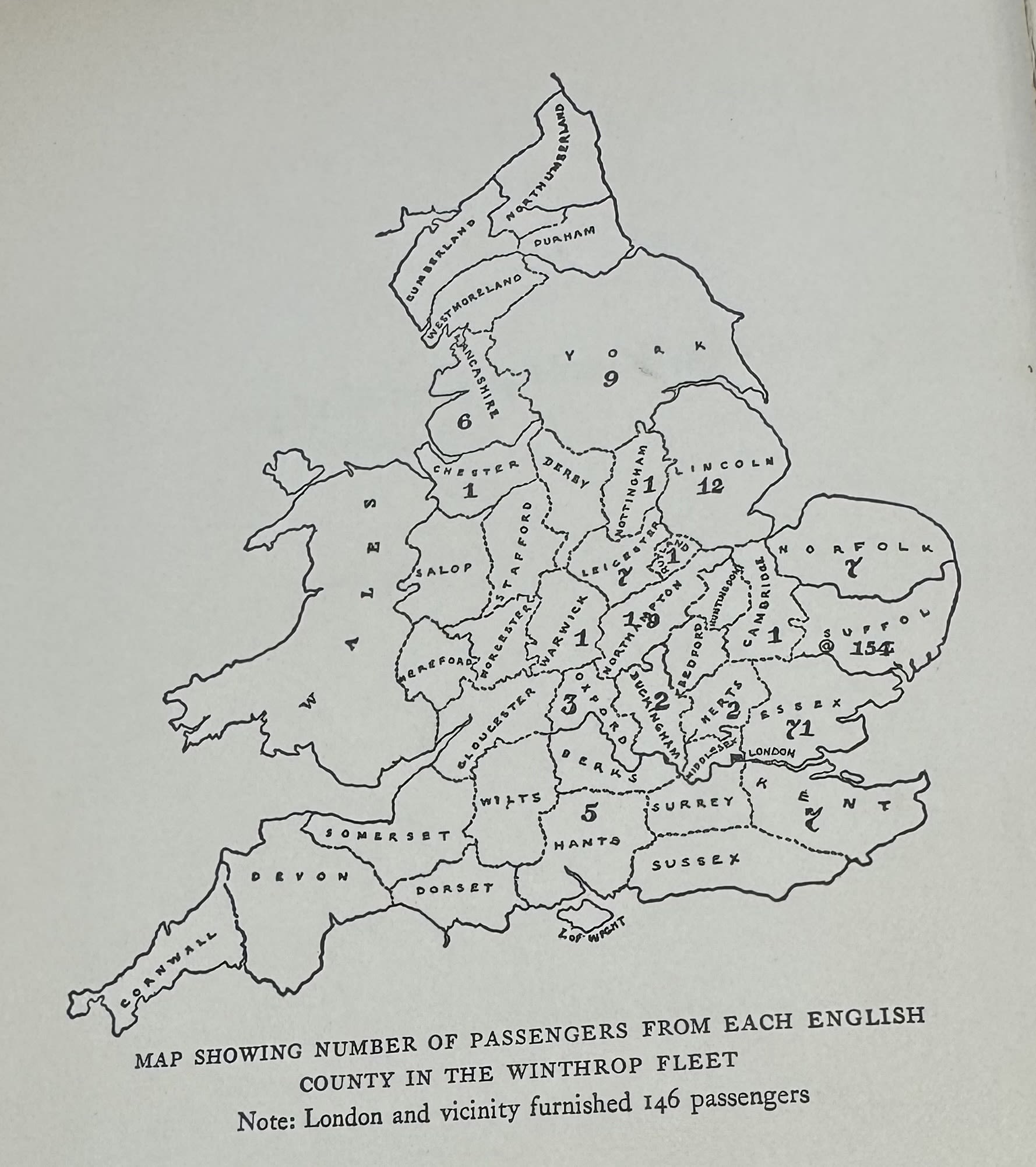

These two sources give an insight into the emigration of Puritans to New England during the Great Puritan Migration of the seventeenth century, with the greatest number of passengers aboard the Winthrop Fleet in 1630 emigrating from Old Suffolk.

Left and Below: Suffolk Archives, Ipswich, 974.02, The Winthrop Fleet of 1630, An Account of the Vessels, the Voyage, the Passengers and their English Homes from Original Authorities

Left: A map showing the number of passengers from each English county aboard the Winthrop Fleet during the voyage of 1630.

Below: A list of the number of English people from London and thirteen English counties who emigrated to New England aboard the Winthrop Fleet during the voyage of 1630.

Who is John Winthrop?

John Winthrop (22 January 1588 [Old Style: 12 January 1587] to 26 March 1649) was a Cambridge-educated English Puritan lawyer, the lord of Groton Manor in Suffolk, and most importantly, the first Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Company and Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Rejecting Old England as a "sinful nation", John Winthrop led a fleet of eleven ships carrying around 700 to more than 1000 Puritan colonists (which included passengers from Suffolk) to New England to establish the Massachusetts Bay Colony (which became the second major settlement in New England after Plymouth) in 1630.

As the colony's first governor, Winthrop had an exalted vision for Massachusetts as a colony where Puritans, as a community, "would worship as the Bible intended them to".

However, why did John Winthrop choose to emigrate from Old Suffolk to New England in 1630? How did he go from a manor lord to the first governor of what would become one of England's most significant colonies? And how did he influence the emigration of other Puritans from Suffolk to America during the mid-seventeenth century?

To answer these questions, this display will make use of several documents that record Winthrop's reasons for emigrating from Old Suffolk to New England and his role in founding the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

Most of these documents will come from the Winthrop Papers, which record the early history of the Massachusetts Bay Colony through the governor's personal writings, letters and journals.

Winthrop's papers also contain the sermons in which he set forth the ideals of a Puritan community in the New World, including his most well-known sermon, "A Model for Christian Charity," or "City Upon a Hill".

This sermon would significantly influence Suffolk Puritans to emigrate to America by providing a powerful vision of the new Puritan community in Massachusetts Bay Colony.

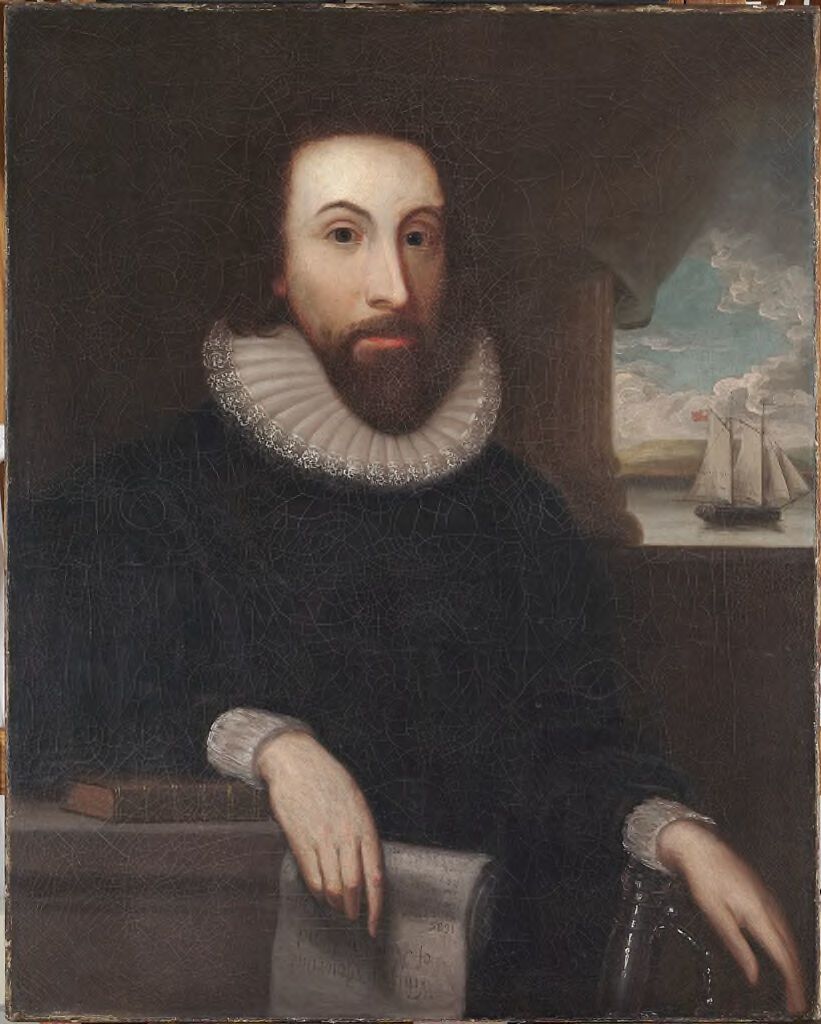

Right: An oil on canvas painting of John Winthrop (1588-1649) at New England on 16 February 1635, c.1750-1775. (Painting provided by the Harvard Art Museums).

Winthrop's Puritan Roots in Old Suffolk

Like most Englishmen, Winthrop's family (which had a record of commitment to the further reform of the Church of England) became involved in the religious struggles between Catholics and Protestants from the sixteenth century, and had been devotedly Protestant since King Henry VIII's reign.

Edwardstone, along with Groton and Boxford, was part of the Stour Valley region in the East of England, a stronghold for Puritan culture and reform during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. John spent most of his life in this region before he emigrated to America, shaping his strong Puritan beliefs.

John enrolled at Trinity College to become a minister, as he was devoted to the Puritan faith. However, his marriage to Mary Fourth ended any chances he had of entering the ministry. Yet, despite abandoning his plans for a ministerial career, he still drew on his faith as a Puritan and placed his trust in God.

In 1613, John returned from southeast Essex to the Stour Valley region, where he reconnected with the clergy and laymen who had helped shape his Puritan faith.

When he became a Justice of the Peace at eighteen years old, he aspired to apply Puritan moral concerns to the task of government, inspired by the godly Puritan magistrates that he had known as a youth. This experience would eventually allow him to shape the structure of Massachusetts Bay Colony's legal system based on Puritan values.

Furthermore, the manor lord actively encouraged his family to follow Puritanism during the early sixteenth century. A key document that represents this behaviour is the letter that he wrote to his oldest son, John Winthrop Junior, on 6 August 1622.

In this letter, the elder John Winthrop urges his son, who is studying in Dublin at the time, to avoid temptations from "ungodly men" and remain devoted to his worship of God.

However, while the Suffolk Commission of the Peace was praised by Puritans as a "stronghold of godly magistrates", this began to change when John joined the Commission.

The rise of conservative forces in the Church of England during the early sixteenth century led to a crackdown on Puritans everywhere in England, including the Stour Valley region. During the 1620s and 1630s, many Puritan clergy were even removed from their jobs by the bishops.

The persecution of Puritans meant that Winthrop could not carry out his civil duties without abandoning his religious faith. This convinced the Suffolk manor lord to begin thinking about creating a new spiritual community for Puritans in America during the late 1620s.

Suffolk Archives, Ipswich: 920 WIN, Winthrop Papers and Letters, Volume 1, 1498-1628.

Suffolk Archives, Ipswich: 920 WIN, Winthrop Papers and Letters, Volume 1, 1498-1628.

Emigration to Massachusetts in 1630

In August 1629, after deciding to emigrate from Old Suffolk, John Winthrop joined with like-minded Puritans in the Massachusetts Bay Company. On 26 August 1629, he and the company's investors wrote up the Cambridge Agreement on 26 August 1629. Winthrop and the investors agreed to embark for New England in the spring of 1630 under one condition: that they would take the royal charter (which the Massachusetts Bay Company received from Charles I on 4 March 1629) and the government with them to the New World.

This plan provided a legal basis for authority in Massachusetts, and reflected Winthrop's intention to bring the colonists the type of government that they had been familiar with in the Old World.

The company's stockholders approved of this plan and on 20 October 1629, they elected Winthrop as the first governor of the Massachusetts Bay Company and the Massachusetts Bay Colony (when he would arrive in America in 1630).

During the winter of 1629-1630, Winthrop laboriously endeavoured to organise a large migration to Massachusetts and by late March 1630, a fleet of eleven ships had been assembled at the port of Southampton (the same port the Pilgrims had sailed from on the Mayflower ten years earlier). This fleet, led by the Arbella, (Winthrop's 350-ton flagship), set sail in early April 1630 with over 700 passengers.

Over seventy men, women and children from Groton and the closely neighbouring villages would migrate with Winthrop in 1630, with the Governor boarding the Arbella with two of Margaret's sons, Stephen and Adam, and being accompanied by his friend John Wilson (ca. 1591-1667), a prominent Puritan clergyman in the Stour Valley region.

This is highlighted by the list of the Winthrop Fleet's passengers in 1630. (Please see the second and third images for this information)

More of Winthrop's family (including his wife Margaret) and neighbours would also emigrate to America over the next five years. Almost 200 of the initial emigrants in 1630 came from Essex and Suffolk. (The counties that bordered the Stour River).

Winthrop boarded his flagship at Southampton with some of his sons. The Arbella was the first of the fleet's ships to arrive in New England, landing at Salem on 12 June 1630. (Please view the first image for further information about the arrival of each of the Winthrop Fleet's ships in America).

Suffolk Archives, Ipswich: 974.02, The Winthrop Fleet of 1630, An Account of the Vessels, the Voyage, the Passengers and their English Homes from Original Authorities. [A record of the Winthrop Fleet's eleven ships arriving in New England in the summer of 1630].

Suffolk Archives, Ipswich: 974.02, The Winthrop Fleet of 1630, An Account of the Vessels, the Voyage, the Passengers and their English Homes from Original Authorities. [A record of the Winthrop Fleet's eleven ships arriving in New England in the summer of 1630].

Suffolk Archives, Ipswich: 974.02, The Winthrop Fleet of 1630, An Account of the Vessels, the Voyage, the Passengers and their English Homes from Original Authorities. [An appendix of the list of passengers on the Winthrop Fleet, with this page including Reverend John Wilson].

Suffolk Archives, Ipswich: 974.02, The Winthrop Fleet of 1630, An Account of the Vessels, the Voyage, the Passengers and their English Homes from Original Authorities. [An appendix of the list of passengers on the Winthrop Fleet, with this page including Reverend John Wilson].

Suffolk Archives, Ipswich: 974.02, The Winthrop Fleet of 1630, An Account of the Vessels, the Voyage, the Passengers and their English Homes from Original Authorities. [An appendix of the list of passengers on the Winthrop Fleet, with this page including Governor John Winthrop and three of his sons].

Suffolk Archives, Ipswich: 974.02, The Winthrop Fleet of 1630, An Account of the Vessels, the Voyage, the Passengers and their English Homes from Original Authorities. [An appendix of the list of passengers on the Winthrop Fleet, with this page including Governor John Winthrop and three of his sons].

Inspiring Other Puritans from Suffolk

In 1630, Winthrop was also accompanied by two prominent Puritan clergymen: Reverend John Wilson (ca. 1591-1667), who had been preaching in Sudbury at the time and Reverend George Phillips (1592/1593-1644), who had been employed in Boxford.

Charles Edward Banks argues that the clergymen's inclusion on Winthrop's voyage may be credited to the Governor's personal influence, confirming that Winthrop was successful in influencing Puritan clergymen preaching in Suffolk to emigrate, even if these clergymen were the only two that joined the Governor in 1630.

Moreover, Governor Winthrop's personal journal reveals that his wife Margaret and their children, (including their eldest son, John Winthrop Junior), also emigrated to New England, and arrived in November 1631. This successfully demonstrates the influence that Winthrop's decision to emigrate had on his closest family.

However, the emigration of Puritans to Massachusetts heavily varied during Winthrop's life, influenced by the challenges posed by the English authorities during the 1630s. In 1634, the English authorities, prompted by Archbishop William Laud of Canterbury, required anyone planning to emigrate to Massachusetts to get licensed. Fortunately, this attempt to prevent further Puritan migration was impossible to fully enforce. Yet only a thousand more emigrants had arrived in Massachusetts by 1634.

Even so, Winthrop was firmly confident that more emigrants would come and 1634, despite the small number of emigrants that year, saw a sudden revival of emigration to New England. (Please scroll down and see the fourth document for an example of this renewed Puritan emigration from Suffolk).

The emigrants from Old England included great landowners and nobles and men of blood and fortune, as well as scholars, merchants and farmers.

In fact, there was a husbandman, from Brampton, Suffolk, named Benjamin Cooper. However, he died whilst sailing on the Mary Anne to New England in 1637.

Moreover, emigrants in Old Suffolk were also compelled to leave in the 1630s by economic adversity, just like Winthrop. (While religion was Winthrop's main reason for emigrating, his financial crisis in the 1620s was still an important contribution for his decision to depart from Suffolk). An example of these emigrants was Thomas Payne, a weaver from the village of Wrentham in Suffolk, who had funds to invest in the New England weaving enterprise and emigrated to Salem in 1637 on the Mary Anne.

Sadly, like Cooper, Payne also died before reaching New England.

By 1639, 20,000 Puritans had emigrated to New England, with three quarters of this number arriving in Massachusetts, much to Winthrop's satisfaction.

This successfully demonstrates the Governor's success at inspiring other Puritans from Old Suffolk, both directly and indirectly.

The outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642 did put an end to the Great Puritan Migration and forced many East Anglians (who were anxious to join their kin overseas) to remain at home and support this war's prosecution. However, by this time, Winthrop had already inspired enough Puritans to emigrate from Suffolk and East Anglia and shape New England based on East Anglian culture.

Suffolk Archives: Ipswich, 974.02, The Winthrop Fleet of 1630, An Account of the Vessels, the Voyage, the Passengers and their English Homes from Original Authorities. [This page is part of the appendix that lists the passengers of the Winthrop Fleet in 1630, and includes Reverend John Wilson's name.]

Suffolk Archives: Ipswich, 974.02, The Winthrop Fleet of 1630, An Account of the Vessels, the Voyage, the Passengers and their English Homes from Original Authorities. [This page is part of the appendix that lists the passengers of the Winthrop Fleet in 1630, and includes Reverend John Wilson's name.]

Suffolk Archives: Ipswich, 974.02, The Winthrop Fleet of 1630, An Account of the Vessels, the Voyage, the Passengers and their English Homes from Original Authorities. [This page is part of the appendix that lists the passengers of the Winthrop Fleet in 1630, and includes the names of Governor John Winthrop and three of his sons.]

Suffolk Archives: Ipswich, 974.02, The Winthrop Fleet of 1630, An Account of the Vessels, the Voyage, the Passengers and their English Homes from Original Authorities. [This page is part of the appendix that lists the passengers of the Winthrop Fleet in 1630, and includes the names of Governor John Winthrop and three of his sons.]

J. Winthrop, A Journal of the Transactions and Occurrences in the Settlement of Massachusetts and the Other New England Colonies from the Year 1630 to 1644; Written by John Winthrop, Esq. First Governor of Massachusetts, (Hartford: Elisha Babcock, 1790). [This page contains the diary entry concerning the arrival of Margaret Winthrop and her children in Massachusetts on 2 November 1631.]

J. Winthrop, A Journal of the Transactions and Occurrences in the Settlement of Massachusetts and the Other New England Colonies from the Year 1630 to 1644; Written by John Winthrop, Esq. First Governor of Massachusetts, (Hartford: Elisha Babcock, 1790). [This page contains the diary entry concerning the arrival of Margaret Winthrop and her children in Massachusetts on 2 November 1631.]

A map detailing the English Origins of Passengers on Seven Ships to Massachusetts between 1635 and 1638, including the number of passengers from each county. (Used with permission and taken from V.D. Anderson, ‘Migrants and Motives: Religion and the Settlement of New England, 1630-1640’, p.357)

A map detailing the English Origins of Passengers on Seven Ships to Massachusetts between 1635 and 1638, including the number of passengers from each county. (Used with permission and taken from V.D. Anderson, ‘Migrants and Motives: Religion and the Settlement of New England, 1630-1640’, p.357)

Above and Below: Robert Ryece's letter to John Winthrop, 12 August 1629, in R.C. Winthrop, Life and Letters of John Winthrop: Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Company At Their Emigration to New England.

[While Robert Ryece's letter to John Winthrop on 12 August is originally part of the Winthrop Papers' second volume, the source from which I have taken the letter comes from Robert C. Winthrop's Life and Letters.]

Opposition to Winthrop's Emigration

While Winthrop was considering whether or not he should emigrate to New England, many of the manor lord's friends tried to dissuade him from doing so by pointing out the dangers that were involved, including the fact that ships were sunk in Atlantic storms before they even reached the New World.

The source that gives us the most insight into the opposition that Winthrop faced when he was considering his emigration is the letter he received on 12 August 1629 from his friend Robert Ryece of Preston, a Suffolk antiquarian. In this letter, Ryece attempts to discourage Ryece from joining the Massachusetts Bay Company and emigrating to the Massachusetts plantation in New England by arguing that he is needed by his friends, family and the Established Church in Old England more than the new plantation in America.

Robert Charles Winthrop, a direct descendant of John Winthrop, also argues that Ryece's letter is the most important source for understanding John Winthrop's character during the events that led up to his departure from Old Suffolk:

"Indeed, we should hardly know where to look for a more striking tribute to Winthrop's character and consequence at the period of his leaving Old England, or to the estimation in which he was held by his neighbours of Suffolk County, than is furnished by this letter of Robert Ryece."

[Quoted in R.C. Winthrop, Life and Letters of John Winthrop: Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Company At Their Emigration to New England, p.329].

This successfully conveys the message that the early chapters of John Winthrop's story of departure also included challenges from friends and acquaintances in Old Suffolk who were against emigrating to America.

Even so, Ryece's letter was also produced on the same day John Winthrop summoned a gathering at Bury St. Edmunds for those who were interested in the emigration.

Although R.C. Winthrop states that Ryece "stands fully acquitted" of not giving John Winthrop enough warning, the time of this letter is crucial because it was only written two weeks before the Puritan manor lord wrote up the Cambridge Agreement on 26 August 1629 and agreed to embark for New England in the spring of 1630.

Therefore, this letter successfully demonstrates that despite the frequent protests of his friends and acquaintances, Winthrop had firmly decided to emigrate from Old Suffolk by the summer of 1629.

Moreover, Andrew Delbanco and Alan Herbert argue that Winthrop drew up a systematic response to all the objections raised against the Massachusetts Bay Company by his Puritan brethren who were opposed to emigration. This was the pamphlet known as "General Considerations for the Plantation of New England, with an Answer to Several Objections", which provided nine reasons for emigrating and colonising the Massachusetts plantation. These reasons included the increasing corruption in England.

Disillusionment with Old England and Seeking a New Life in Massachusetts

Winthrop's disdain for Old England was the result of various problems that he suffered from during the 1620s as a victim of the religious persecution of Puritans under Charles I. The Puritan manor lord even realised that he would never be able to achieve fame and fortune without sacrificing his religious values.

The first two pages on the right-hand side come from the preface of the second volume of the Winthrop Papers (1623-1630), and they provide important details about the events that encouraged the Puritan manor lord to emigrate from Old Suffolk. In particular, the first of these pages is important because it demonstrates that Winthrop chose to emigrate from Suffolk because he was a victim of religious persecution during the early years of Charles I's reign.

This also reflects how the Puritan colonists, when they emigrated to New England from 1630 to 1642, were united in their belief that they were "victims of religious persecution in England", and that the New World "provided them with a canvas on which they could paint their own church in accord with their own beliefs."

Moreover, although the second page on the right-hand side confirms that Winthrop was already thinking about emigration to New England by July 1629, the earliest hint of his plans for departure is conveyed in his letter to Margaret on 15 May 1629, as previously mentioned in this display's fifth slide.

This is supported by the third and fourth pages on the right-hand side, which come from Alice Morse Earle's records of Margaret Winthrop's life and indicate that John Winthrop believed that England had become increasingly corrupt and unsuitable for religious practices, having witnessed several important events that concerned religion during the early seventeenth century.

Another key factor that convinced Winthrop to emigrate was the financial crisis that he suffered from during the 1620s, which included a national economic decline that affected many landholders during the seventeenth century. The Puritan manor lord struggled to provide for his growing family and maintain a way of life appropriate for his social standing.

He believed that these problems "were God's way of weaning him from his life in England so that he might be more inclined to go through the new door to service God in America".

This is supported by Virginia DeJohn Anderson, an American historian who has written about seventeenth-century America, including the migration to New England. Anderson argues that historians disagree on the precise causes of the emigration to New England, with some believing religious motives were the main reason, while others insisted that "a desire for economic improvement lay at the heart of the migration".

Finally, Winthrop believed that the foundations for learning and religion in England were corrupted, with Charles I attempting to suppress the spirit of Puritanism in educational institutions such as the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge.

Above: Suffolk Archives, Ipswich, 920 WIN, Winthrop Papers and Letters, Volume 2, 1623-1630.

Below: Suffolk Archives, Ipswich, 920 WIN, Margaret Winthrop.

John Winthrop's Legacy in America and England

Although the Massachusetts Bay Company's charter was revoked by the English courts in 1684 (subjecting New England to rule by an English Governor-General), by then, the values that John Winthrop had helped to build in the region (these included a moral approach to politics and participatory government) were too well-established to be uprooted.

The leaders of Revolutionary Massachusetts in the eighteenth century would draw upon their Puritan heritage and fondly remember Winthrop, with New Englanders remembering him as the founder of Massachusetts.

Moreover, Winthrop's "A Model of Christian Charity" has become one of the most renowned sermons in American history, with this model still mattering as part of the American identity today. The United States of America has also achieved a near-monopoly control over the phrase "city on a hill".

Twentieth-century American presidents John Fitzgerald Kennedy and Ronald Reagan have also famously used this phrase. JFK used "city on a hill" in his speech to the General Court of Massachusetts on 9 January 1961, launching the phrase into contemporary American politics and culture. Reagan used the phrase in his farewell address to the nation on 11 January 1989.

Furthermore, while the Winthrops' manor house no longer stands in England today, the Church of St. Bartholomew's in Groton has become something of a shrine to John Winthrop's memory.

Since the mid-nineteenth century, Winthrop's descendants have helped to maintain the old parish church and memorialised their distinguished ancestor in stained glass windows and bronze plaques.

Ultimately, John Winthrop's fateful decision to depart from Old Suffolk, influenced by his disillusionment of a religiously corrupt England that persecuted Puritans like him, would cause many people in England and America to remember the upper-class manor lord as one of the most important founding fathers in seventeenth-century America.

Winthrop's desire to establish a refuge for free Puritan worship in the New World would not only lead to him establishing one of New England's most important colonies, but also the foundations of New England's religious and political systems from the mid-seventeenth century.

Finally, Winthrop's efforts to preach his ambitious vision for Massachusetts would also convince multiple Puritans from Suffolk and East Anglia to join him in the New World, shaping New England's religious culture during the seventeenth century.

Stained glass windows depicting Governor John Winthrop in St. Bartholomew's Church at Groton, Suffolk. (The picture of this memorial window collection can be found on the Britain Express website, and has been made available for licensing by the Britain Express image library).

Stained glass windows depicting Governor John Winthrop in St. Bartholomew's Church at Groton, Suffolk. (The picture of this memorial window collection can be found on the Britain Express website, and has been made available for licensing by the Britain Express image library).