House and Home

Every Home Tells a Story

Family Homes

Our houses and homes often vary massively. Some have 500 years of history and have been recognised as being of national importance with the listing system. Others have been built only recently yet speak to our modern society and what we believe to be of importance, from how many bedrooms we need, to the materials we use. Homes, whatever shape and size they come in, form a huge part of our lives and often provide us with a place of comfort and safety.

22 Britannia Road

Both the physical and online House and Home exhibitions were inspired by our archives and by '22 Britannia Road', an historical fiction book written by author and University of Suffolk lecturer Dr Amanda Hodgkinson.

It is 1946 and Silvana and eight-year-old Aurek board a ship that will take them from Poland to England. Silvana has not seen her husband Janusz in six years, but, they are assured, he has made them a home in Ipswich.

However, after living wild in the forests for years, carrying a terrible secret, all Silvana knows is that she and Aurek are survivors. Everything else is lost. Meanwhile Janusz, a Polish soldier, who has criss-crossed Europe during the war, hopes his family will help put his own dark past behind him.

But the war and the years apart will always haunt each of them unless they together confront what they were compelled to do to survive.

‘Janusz thinks the house looks lucky. He steps back to get a better look at Number 22 Britannia Road, and admires the narrow red-brick property with its three windows and blue door. The door has a pane of coloured glass set in it: a yellow sunrise sitting in a green border with a blue bird in its centre. It’s so typically English it makes him smile. It’s just what he is searching for’

The real 22 Britannia Road is a terrace house in Ipswich built in 1912.

Britannia Road is in the California district of Ipswich which was formed from the sale of the 98-acre Cauldwell Hall estate in 1849. The land between Woodbridge Road and Foxhall Road was bought by the Ipswich & Suffolk Freehold Land Society and divided into 282 building plots which were sold to society members for £23.

The Freehold Land Society was an organisation set up to promote affordable homeownership for working people which therefore gave them the vote. The society enabled workers to invest their savings to be used to acquire areas of freehold land, which would then be divided into building plots, and houses built by the owners.

Housing Estates and Prefabs

One well-known feature of the post-war period was the building of many new housing estates, often largely made up of council housing. These estates were built to combat country-wide expanding populations and post-World War Two housing shortages. There was also a growing call from some members of society for new houses that were more spacious than those built in the past, with more living space and room for increased vehicle-use.

The housing types often seen on these post-war housing estates commonly vary from detached or semi-detached properties mixed with a range of bungalows. These bungalows were another common feature of post-war housing estates with new pre-fabricated bungalows gaining popularity.

Clover Close

Clover Close is situated in the Chantry estate, close to Gippeswyk park to the south of Ipswich and comprises of some twenty detached and semi-detached houses; built during the 1950’s, to combat Ipswich’s expanding population and post war housing shortage.

Chantry estate predominantly contained council housing and was at the time of its development, one of the largest council estates in Britain. It now has a population of over 30,000.

Clover Close, akin to many other areas in the Chantry estate, was built on former farmland. However, evidence unearthed by archaeologists during the estates construction, suggests that the land was also likely the site of a Roman settlement, due to its location on high ground overlooking the River Gipping.

Although the houses within the older section of the Chantry estate are not grand houses or of architectural note, the housing estate nonetheless is an excellent example of a publicly funded estate, designed to provide aspirational modern housing with ample space provision, parkland, and adequate local transport links. The estate upheld the ideology behind pre-war ‘garden city’ designs, of the importance of communities surrounded by a ‘green belt’ of parkland and wooded areas.

Inverness Road Pre-fabricated Bungalows

Pre-fabricated houses, specifically bungalows, began to grow in popularity in the period after World War Two. Pre-fabricated houses are called this because they are constructed from premade parts which means they can be put together quickly and affordably. Most cost around £1000 to build at the time. Many of these units were made across the UK in response to the housing shortage post World War Two. They were intended to only last 10-15 years. Many were bungalows with clever use of a small floorplan, and equipped with all the mod cons of the time.

K681/1/266/23 - A prefabricated bungalow called 'Homeleigh' in Kelsale, 1935

K681/1/266/23 - A prefabricated bungalow called 'Homeleigh' in Kelsale, 1935

There are several areas of pre-fabricated bungalows around Rushmere in Ipswich. They were threatened with demolition in 2013 but local residents successfully campaigned to save them as they loved the layout of their homes and the large gardens. Ipswich Borough Council renovated the houses in 2015 including adding better insulation and double glazing. The houses are to this day popular with residents and many have been bought by the former tenants under the right-to-buy legislation.

K681/1/63/9 - A photograph showing a young child standing at the end of one of the New Village Xylonite streets

K681/1/63/9 - A photograph showing a young child standing at the end of one of the New Village Xylonite streets

Industry-provided Accommodation

You may have heard of such 'company villages' as Bourneville. Here, the owners of Cadbury built a village in the countryside with the intention of housing their workers away from the poor living conditions of the industrialised city centres. Bourneville included large homes complete with spacious gardens and good sanitation. The village gave workers access to sports fields, playgrounds and swimming pools, alongside daily Bible readings and prayer groups.

'Company villages' are not the only type of industry-provided accommodation, and there are a number of examples of these homes to be found across Suffolk throughout history.

Xylonite Houses - New Village, Brantham

Altitude sickness is rare in Suffolk but following the A137 from Ipswich to Manningtree you rapidly drop several hundred metres down into the basin at the estuary of the Stour and Cattawade Creek. On the way down the A137 into Manningtree you pass New Village – three streets of houses which were built in the late 1880s by the British Xylonite company for their workers.

Although Brantham was not a “company town” like Bourneville in Birmingham, the relationship between the company and its employees went beyond a simple purchase of labour. The company built the village hall and supported sporting activities. The local bowls club still features the Xylonite logo – an elephant and a tortoise. The company boasted that xylonite could replace ivory and tortoiseshell in brushes and combs, and so promoted animal welfare.

The British Xylonite company began life in east London in the latter part of the nineteenth century, making an early form of plastic known as Xylonite or celluloid. In 1877 the company established a new factory on the Essex /Suffolk border attracted by cheap land, ready access to water and a railway line. Farms were purchased to create a new industrial site.

The census entries for New Village in 1891, 1901 and 1911 indicate that, in many cases, the adult tenants were born in East London and their offspring were born in Brantham.

The streets named New Village consist of around sixty semi-detached houses in three streets. The houses are of similar design and many feature an open porch at the corner of the house with a distinctive column. The current condition of the houses varies from pristine to “investment opportunity”, and almost all appear to be occupied.

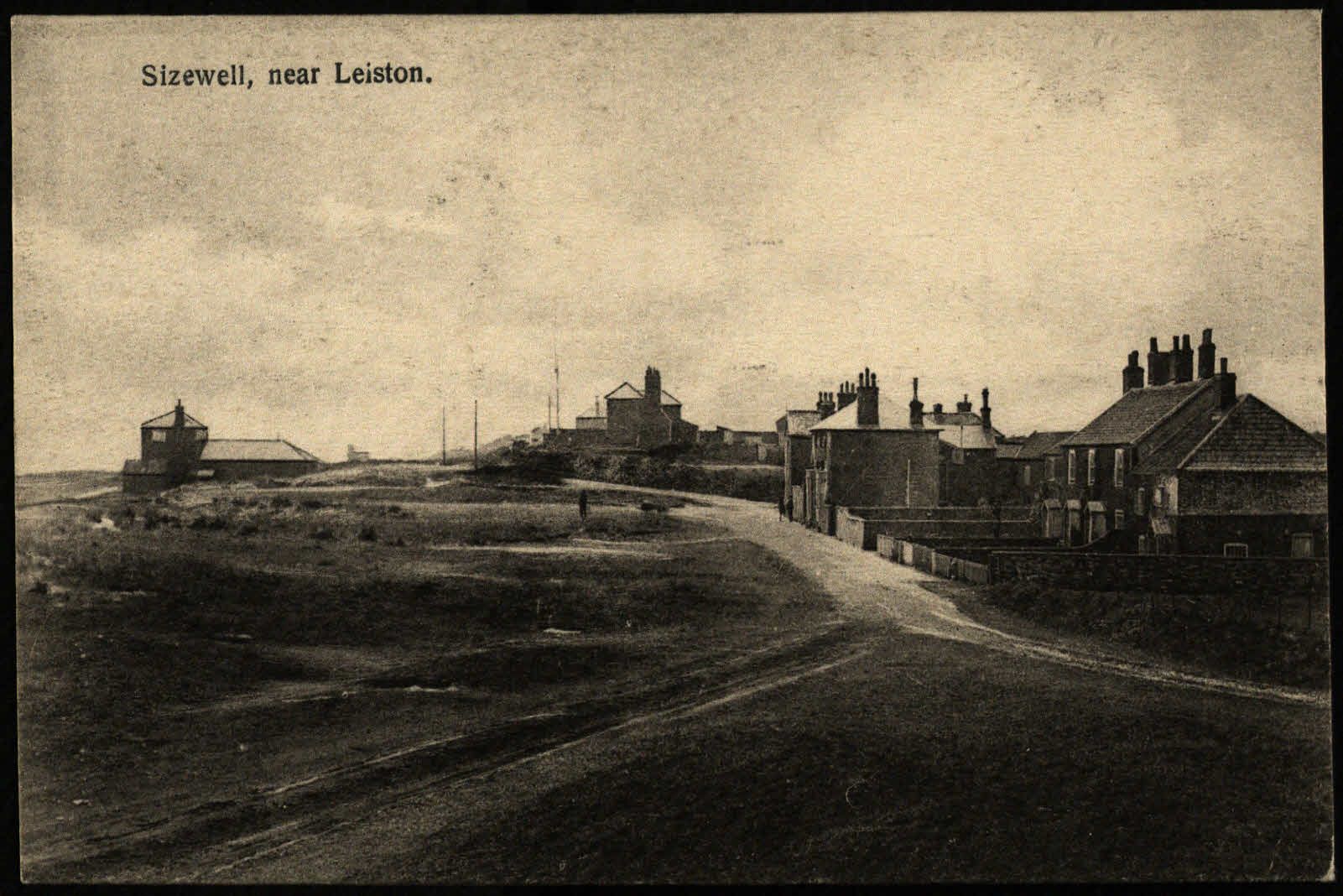

Sizewell Coastguard Cottages

The Coastguard was formed in 1822 by the amalgamation of three services set up to prevent smuggling: the Revenue Officers, the Riding Officers the Preventive Water Guard. From 1856 the duties of the Coastguard were defending the coast, providing a reserve for the Royal Navy, and preventing smuggling. The role also had some life-saving responsibilities and in the 1920s, along with coastal observation, this became its main role.

Until the late 20th century, accommodation was provided for most ranks of the Coastguard service and their families, often comprising a row of cottages. Sometimes the senior officer’s house was built separately, otherwise it might be at one end of the terrace. Sometimes the senior officer’s house contained a watch room (later known as a duty room), though this was provided with separate access and unconnected to the residence. It was sometimes provided with a canted bay window from which a watch could be maintained. In other coastguard stations the watch room was a separate structure.

At Sizewell the coastguard station appears to have been purpose built with a terrace of cottages and separate watch house. The watch house has been dated to the 1820s and if the cottages are contemporary with the watch tower, they are earlier than the coast guard cottages at nearby Dunwich.

Evidence of the Coastguard station and cottages at Sizewell can be found on OS maps dated 1884, 1904 and 1927. The map shown here shows evidence of the coast station at Sizewell and whilst not dated, is estimated to have been created earlier than 1835.

K681/1/283/47 - A photograph showing the Sizewell coastguard cottages overlooking the coast

K681/1/283/47 - A photograph showing the Sizewell coastguard cottages overlooking the coast

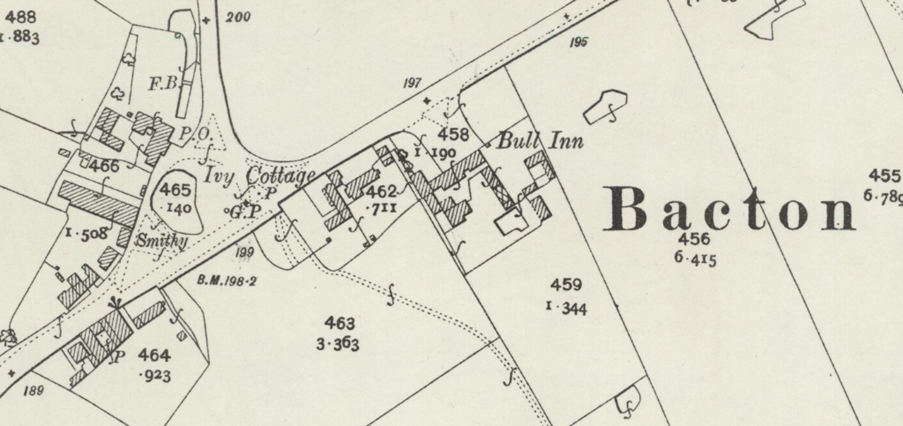

The Bull Inn, Bacton

One form of industry-provided accommodation that is less often thought of is the local pub. For centuries, landlords or ladies of pubs have lived on site, often in the residence above. This is the case with The Bull Inn, that records show has been operating since before the eighteenth century.

Whilst the thatched, timber-framed and plastered building itself hails from the 17th century, the first mention of The Bull Inn comes from an article in the Ipswich Journal on 30th October 1790, where an auction was planned.

The pub then continued to be featured in local newspapers as a place where auction catalogues could be collected by interested parties. Aside from the occasional auction, the Bull also hosted the meetings of the Bacton Association for Prosecuting Felons in the 19th century. During the time of the Bacton murder of 1853, the magistrate’s court hearings were held at the Bull.

Historically pubs and beerhouses were the hub of the community, and that is certainly the case for The Bull Inn. They provided recreation for the community and often served as venues for public meetings, auctions and even court proceedings.

Aside from the business side of the establishment, the Bull Inn has also been a residence for many landlords and landladies, and their families. Various families in connection with the pub can be traced back to the year 1812, beginning with a Mr Pettit of the Bull Inn at Bacton, whose daughter Ann was married in April of that year. The Woods family had taken over by 1833 and so began The Bull's golden era. The pub remained in their ownership for over 50 years. Samuel Woods and especially his son Charles, who assumed control in the 1850s, became recognised locally for their business acumen, their hospitality and their honesty.

It can be deduced from the 1861 census that Charles Woods businesses were generating a significant income. In the farm, maltings and brewery he employed 5 men and 1 boy and in his carpentry business he employed 4 men. He also employed a house servant, barmaid and 2 horsemen. All this is evidence of a thriving pub.

The reputation wasn’t just built on beer and food. It is evident from the newspapers of the time that neither Charles Woods and his late father Samuel would tolerate drunkenness or intimidation. The Diss Express of 14th April 1876 reported that at the Hartismere Petty Sessions, John Wilding and Edward Wilding of Bacton were charged with being drunk and refusing to leave the pub when asked to do so by Charles Woods. John Wilding had apparently quit the pub a minute or so after being asked, but the magistrates took a very dim view of his companion Edward’s behaviour and fined him 12s 6d, which he paid, the alternative being 7 days imprisonment.

Records show that the pub was sold to a Mr. Bantock in 1887, however the Woods remained in their position as Innkeeper, and Charles Hector Woods took over from his father, Charles, following his death in 1889. Their time at The Bull Inn came to a close when the Whistlecraft family took over in 1901.

The Bull Inn is still in operation today, and sits in The Street between St Mary’s Church and Shop Green in Bacton, Suffolk. This pub is a prime example of how a business can simultaneously sit at the heart of community life whilst also providing a home for the families in charge over the centuries.

25” Ordnance Survey sheet, 46/3, 1904 edition showing the Bull Inn at Bacton

25” Ordnance Survey sheet, 46/3, 1904 edition showing the Bull Inn at Bacton

K681/1/16/21 - A photograph of a village procession outside The Bull Inn. The procession is thought to have taken place for Queen Victoria's 50th Birthday in 1869.

K681/1/16/21 - A photograph of a village procession outside The Bull Inn. The procession is thought to have taken place for Queen Victoria's 50th Birthday in 1869.

Care Homes

An often overlooked aspect of 'House and Home' are the various types of care home. Suffolk has a number of this type of home, including the first residential home opened by Sue Ryder, whose charity continues to operate today.

Devonshire House

Devonshire House in Cavendish was the first Sue Ryder care home opened in 1953 after the property was purchased by Sue Ryder from her mother Mabel.

In 1959, the house was extended and Sue Ryder married Leonard Cheshire who had also been actively setting up care homes for disabled people across Europe after the Second World War.

“Do what you can for the person in front of you”

Many of the residents at Devonshire House were survivors of concentration camps but later the focus of the charity broadened from to care for lives altering disability to those with terminal conditions whether physical or neurological such as Parkinson’s Disease and Huntington’s Disease. A chapel and individual rooms were built for residents and some of them lived in Devonshire House for over 20 years.

Former staff recall memories of Sue Ryder emphasising that Devonshire House should operate as a home and never become institutional. Residents were asked to live together as a family and could do as they pleased.

“There were up to 70 people living with us… It was a very happy home and I felt enriched by the experience of living with so many different people”

“Wonderful evenings of music in the drawing room – especially at Christmas. “Slaves” made music – and the Hungarian gentleman joined in on the trombone. There was a brilliant pianist too, arthritic hands but still able to play beautifully”

The house suffered a flood from the river Stour in 1968. In 1972 there were calls from the government for improvements to staffing following a nurse drowning in the lake, a resident killing themselves, and another running away to London.

The last residents left in 2001 but Devonshire House continues to be operated as a care home today under different ownership.

Hope House Orphanage

Hope House Orphanage, also known as 'East Suffolk Girls Home' and 'House of Hope' Orphanage, was founded on 1st January 1875 by a local businessman and philanthropist called Edward Grimwade and Harriet Isham Grimwade. Harriet Grimwade was also a member of the Ipswich Women’s Suffrage Society and active in local charitable issues. The orphanage was originally situated at 14 Church Street, in the parish of St Clement, Ipswich.

In the 1881 census, there were 20 girls between the ages of 6 and 13 recorded to be living at the orphanage. The matron of House of Hope was a woman named Sarah Leathers and Elizabeth Heyward was the schoolmistress.

In January 1883, the orphanage moved into new buildings, situated at 158 Foxhall Road on the corner of Alan Road, and was established under a Deed of Trust. The new orphanage could accommodate up to 40 girls between the ages of 3 and 10 years old at their date of admission.

Whilst living at Hope House, Girls were trained for domestic service and had to complete household task around the orphanage itself. They received an elementary education, learned to make and to mend their own clothing and were also taught to knit.

K681/1/262/715 - Postcard sent in 1913 featuring Hope House Orphanage

K681/1/262/715 - Postcard sent in 1913 featuring Hope House Orphanage

The orphanage was closed in 1940, and the building was then sold on in 1942. During the war, the premises were used to house Land Army girls and often called ‘The Hostel’.

Seckford Almshouses

Seckford Almshouses was founded in 1587 by Thomas Seckford, a wealthy lawyer and landowner who was granted permission by letters patent from Elizabeth I, to build seven almshouses within his hometown of Woodbridge.

The almshouses were to provide relief for 13 poor men of the parish and to be generously endowed with the revenue from Seckford’s properties in Clerkenwell, London, which at the time gave the almshouses an income of over £112 a year. Although Thomas Seckford died in the same year that his almshouses were founded, his will decreed that the almsmen were to have use of the gardens and lands nearby, be supplied with fuels and gowns and to also receive a pension of £5 a year.

The almshouses were erected on the site of what is now Seckford Street, situated opposite Fen Meadow and was formed by seven residences comprising of a ground floor and an attic storey. Six of the dwellings housed two men each, whilst the seventh ‘principal’ dwelling, housed the almshouse warden. By 1748, accommodation for the nurses serving the almshouse had been built in a new building alongside.

An increase in revenue with the expansion of London meant that Seckford Hospital was built between 1834-1842 on the same site as the almshouses. Though called 'Hospital', this new building was only used as another almshouse, increasing the total number of residents by 27 and creating space for 6 more nurses. The renovations added a chapel to the site, as well as partly demolishing and improving the original 16th century almshouses.

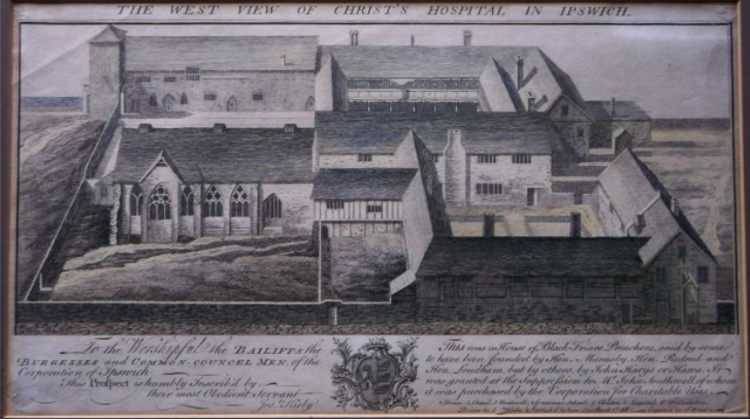

Tooley and Smart Alms-house

Henry Tooley was the richest merchant of Tudor Ipswich and left the bulk of his estate to the poor of the town. On his death in 1551 his will states it was for the building of almshouses for 10 townsmen injured in action.

The Tooley and Smart almshouse was built in the 1550s on a site in what is now Foundation Street. It originally consisted of five separate lodgings, each to accommodate two people.

Tooley's Foundation was established in 1562 as an institution for the welfare of Ipswich's poor.

In 1569 Christ's Hospital was established on a nearby site by Ipswich Co-operation. There was close co-operation between the two institutions. The numbers of Tooley's almspeople were increased alongside. By the mid 1580s the Tooley Foundation consisted of two lodgings housing over forty people.

Christ's Hospital, Ipswich. October 1930. Engraving: drawn by Joshua Kirby and published by him 25th March 1748. HD4052/85/22

Christ's Hospital, Ipswich. October 1930. Engraving: drawn by Joshua Kirby and published by him 25th March 1748. HD4052/85/22

Money was raised for the foundation from Tooley's manors and land across the country, and through donations from other local people. In 1599 a man called William Smart bequeathed a farm and lands in Kirton and Falkenham to Ipswich Corporation for charitable purposes.

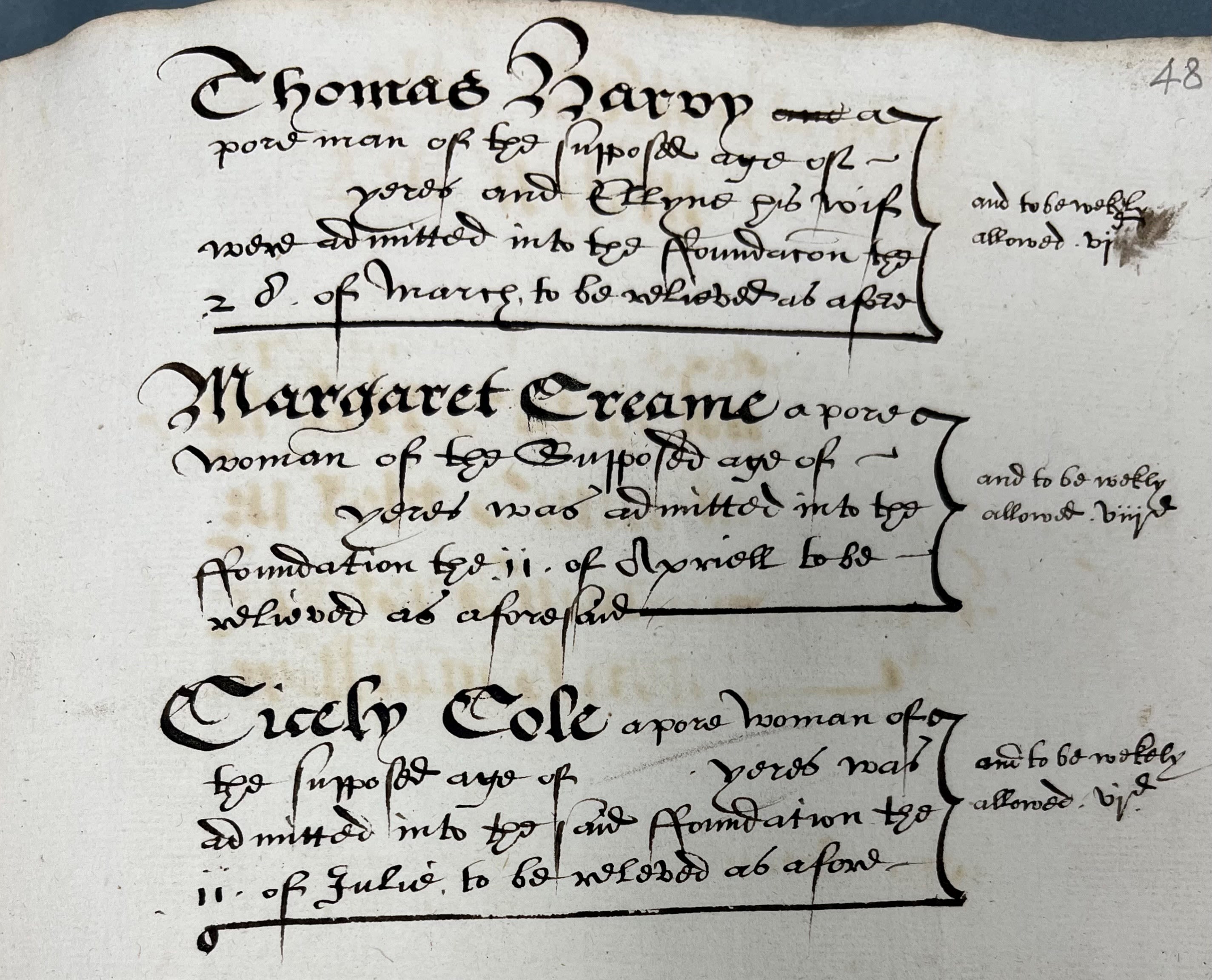

C/5/1/1/3 - Extract from the register of admissions to the Tooley and Smart Almshouse

C/5/1/1/3 - Extract from the register of admissions to the Tooley and Smart Almshouse

The almshouse was rebuilt in 1846 by an architect named John Medland Clark, who also designed the Customs House located on the Waterfront.

K484/28/1/1 - Tooley Almshouses

K484/28/1/1 - Tooley Almshouses

K474/364 - The House in the Clouds

K474/364 - The House in the Clouds

Grand Designs

House in the Clouds

The House in the Clouds was originally built in 1923 to provide a water tank for Thorpeness, a new development with the aim of creating the ideal holiday village.

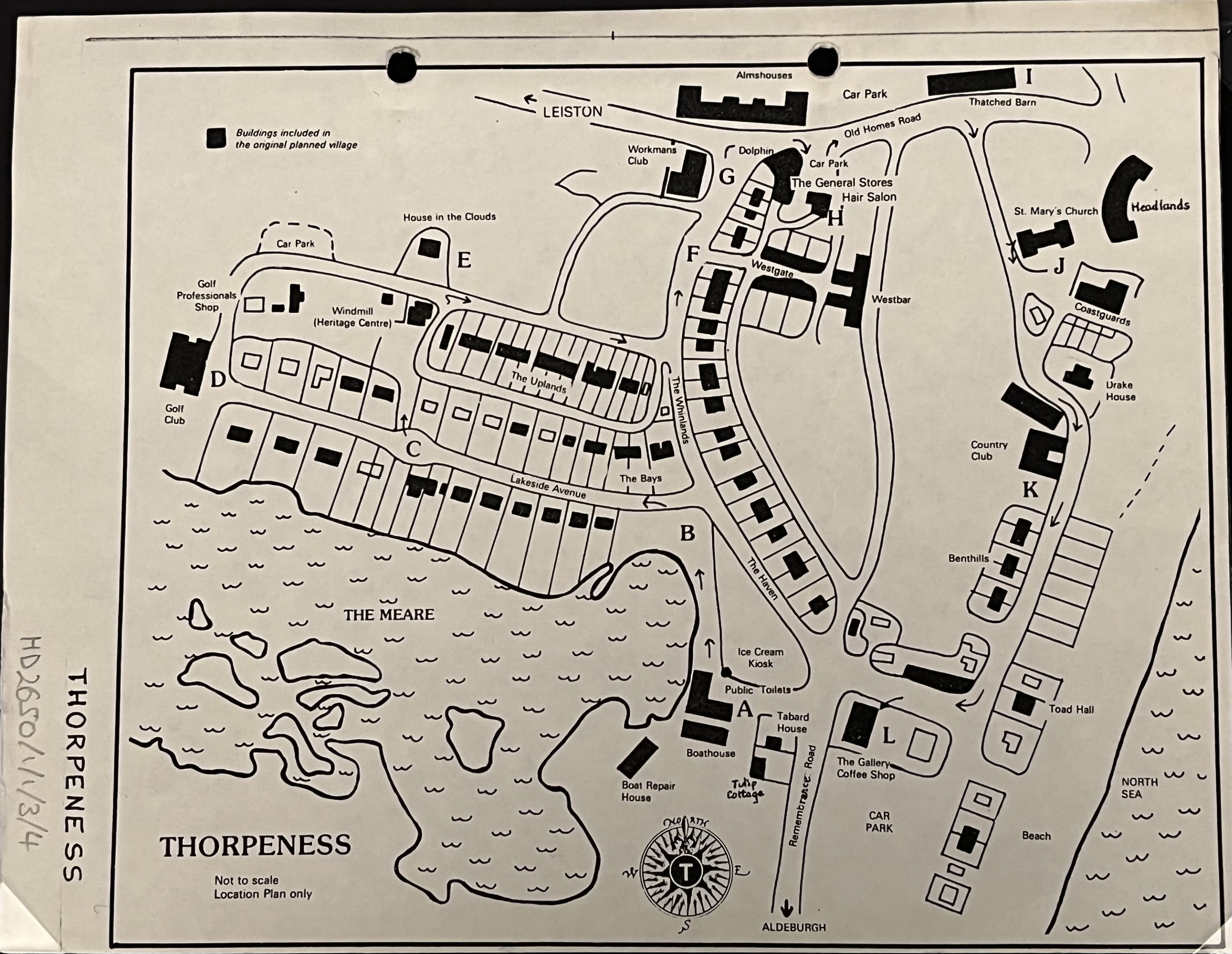

HD2650/1/1/3/4 - Plan of buildings in the centre of Thorpeness

HD2650/1/1/3/4 - Plan of buildings in the centre of Thorpeness

Glencairne Stuart Ogilvie's vision for Thorpeness was to create a type of fantasy village, complete with a Peter Pan-themed lake, so an industrial feature would have looked out of place. Ogilvie, along with F Forbes Glennie, the architect for the village and H G Keep, the works manager, decided to disguise the water tank as a house.

Housing a capacity of 50,000 gallons of water, providing sufficient water for the whole village, the House in the Clouds is visible from miles around as what looks like a 70ft high cottage perched amongst the tree tops.

Originally called 'The Gazebo', Mrs Malcolm Mason, a writer of children’s books and a friend of Ogilivies, was the first person who lived in the house under the tank and renamed the building the House in the Clouds to keep with the fantasy fairy-tale feel of the village.

During WWII, the south-east corner of the tank suffered extensive damage from an English Bofors shell in 1943, which reduced the capacity of the tank to 30,000 gallons. The Misses Humphreys were living in the tower at the time but amazingly slept through the ordeal.

The tank ceased to be used for water storage in 1963 and the property was bought from the Ogilvie family in 1977. Two years later, the tank was removed and converted into a large two-storey games room. A refurbishment of the property and restoration of the garden was carried out in 1987.

House in the Clouds was given a Grade II listing by Historic England in 1995. The property now has 5 bedrooms and 3 bathrooms, 68 stair and large 'room at the top'. Nowadays it is available to rent as holiday accommodation.

Ballingdon Hall

Ballingdon Hall can be dated back to the 1590s when this fine Tudor building was built by Sir Thomas Eden.

Throughout its long history Ballingdon has undergone many changes, with research suggesting that the Hall was originally built in the shape of a capital H. The Hall lost its wings after being converted into a farmhouse in around 1741, leaving just the central crossing.

Despite this long history, Ballingdon is most famous for a plan to put the entire house on wheels and move it up the hill at Easter 1972. The Hodges, the owners at the time, decided to move Ballingdon Hall further up the hill to obtain better views over Stour Valley and escape from the coming development of a new residential estate, Lime Grove.

The move was reportedly inspired by a 1960s project in Egypt to move the temples of Abu Simbel to escape potential damage by nearby development. Over 10,000 people came to see the move and 10p admission was charged for each person. There were traffic jams all through the town.

The moving of Ballingdon Hall, Sudbury Suffolk, 1972. Filmed on Super 8mm cinefilm. Reproduced by kind permission of Tim Leggert.

When it comes to the move itself, the 170-ton house was raised onto 26 wheels and wooden slats, before being dragged half a mile up a steep hill and placed back down at the top.

Whilst the move was only supposed to take 1 week, in the end the move took one whole year. It took another 5 years to put five chimneys, bay windows and fireplaces back in their place which they were removed to lighten the weight of the building during the move. Other than these extra features being removed, it was a condition of the planning permission that the house be moved in one piece.

The house remained with the Hodges family until it was sold in 2020. It is now home to luxury retreats and events.