Suffolk's Weather Prophet: Orlando Whistlecraft

Meet Orlando Whistlecraft

‘On many accounts, “Old Whistlecraft” is a man of whom Suffolk will be proud in the years to come, when the history of the science in which he is interested comes to be written.’

Orlando Whistlecraft is a name that jumps out from the historical record - and it jumps even higher when it is followed by the description 'the weather prophet of Thwaite'. What exactly is a weather prophet, who was Orlando Whistlecraft, and why are the records he made useful today?

This was the starting point for the project Suffolk's Climate: Past, Present and Future. The project team has been researching Whistlecraft's life, and exploring the extensive weather records he kept over six decades to see what they can tell us about how Suffolk's climate has changed since the 19th century.

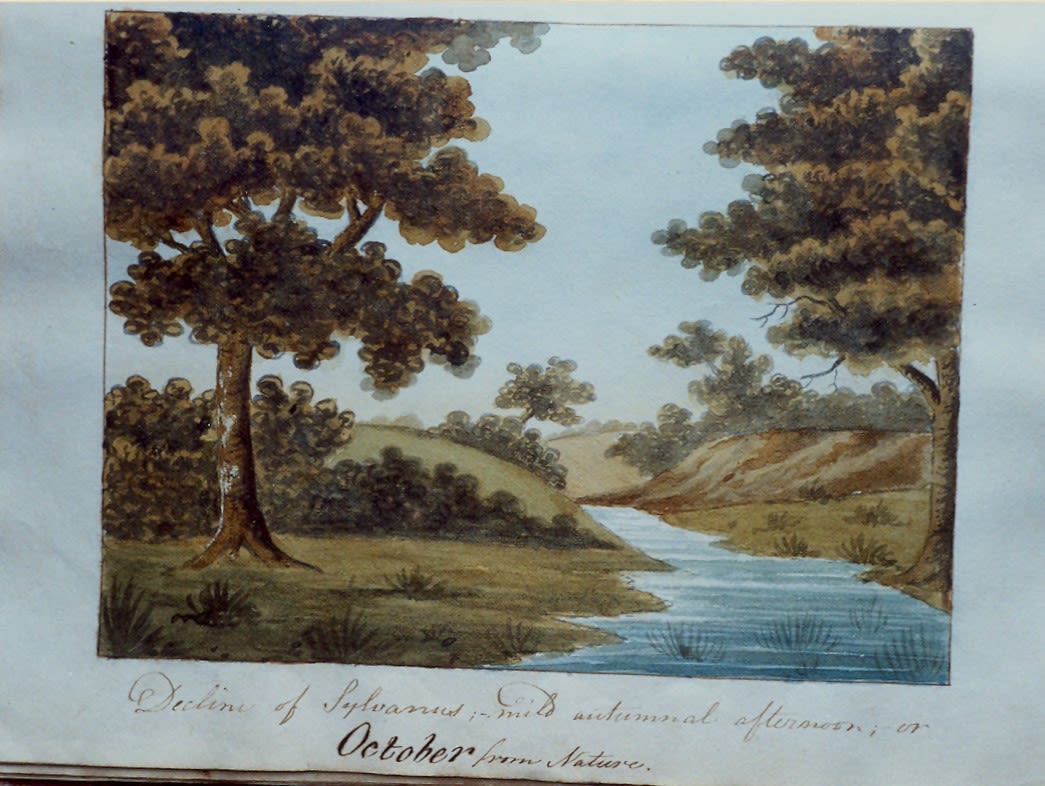

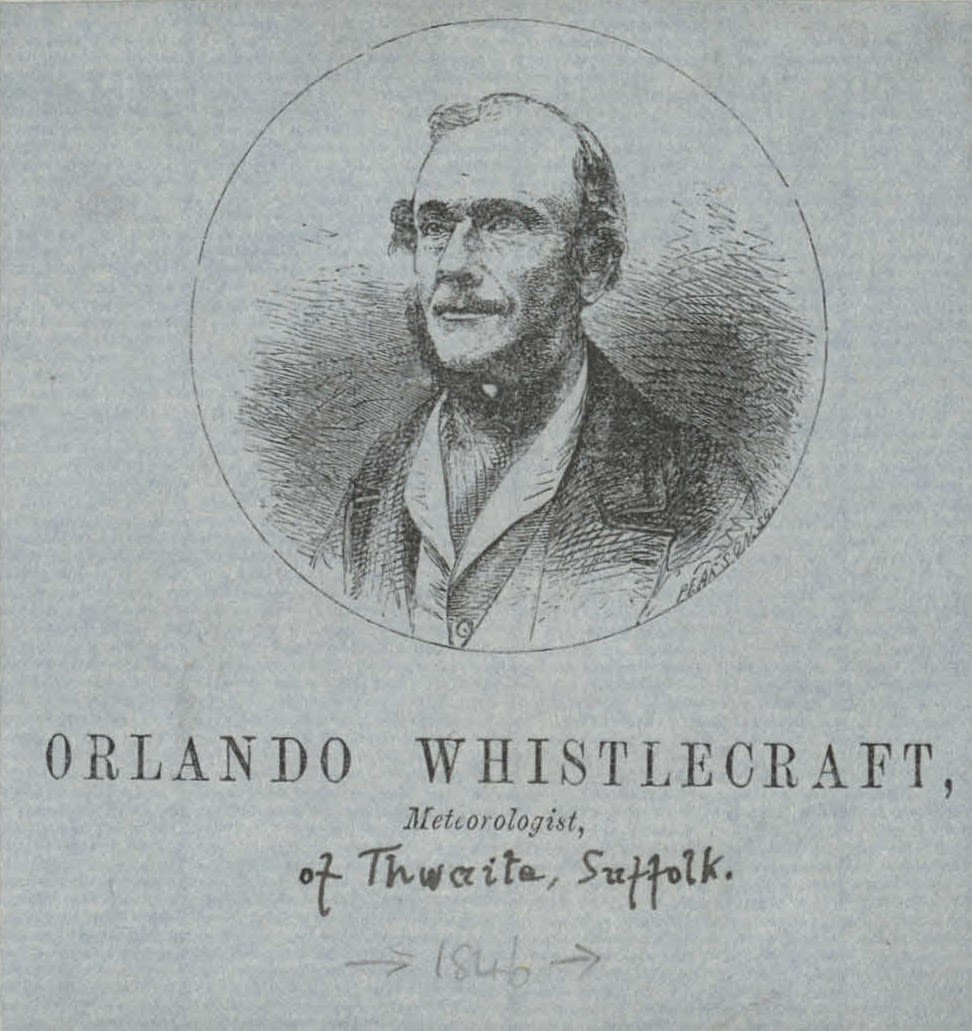

Whistlecraft was born in 1810 and lived until 1893, his life neatly spanning almost an entire century. For over 60 years he made a detailed study of the weather from his Suffolk garden, and published annual almanacs in which he attempted to predict the weather for the entire coming year. He also included notes on what different plants and animals you could expect to see as the seasons changed. Whistlecraft was also an artist, painting and drawing the natural world, weather, and the people he saw around him. You will see several of his sketches and paintings throughout this display.

He made predictions when weather forecasting was still very primitive, and published his predictions in newspapers and a yearly almanac.

According to a description of him in the Suffolk and Essex Free Press in 1859, Whistlecraft was of above average height, with dark curly hair and 'a profusion of whiskers'. He had 'earnest' grey eyes, which lit up 'a thoughtful and meditative countenance'. He had an excellent memory and a 'natural vivacity of disposition'.

Print of Orlando Whistlecraft (PR/W/10)

Print of Orlando Whistlecraft (PR/W/10)

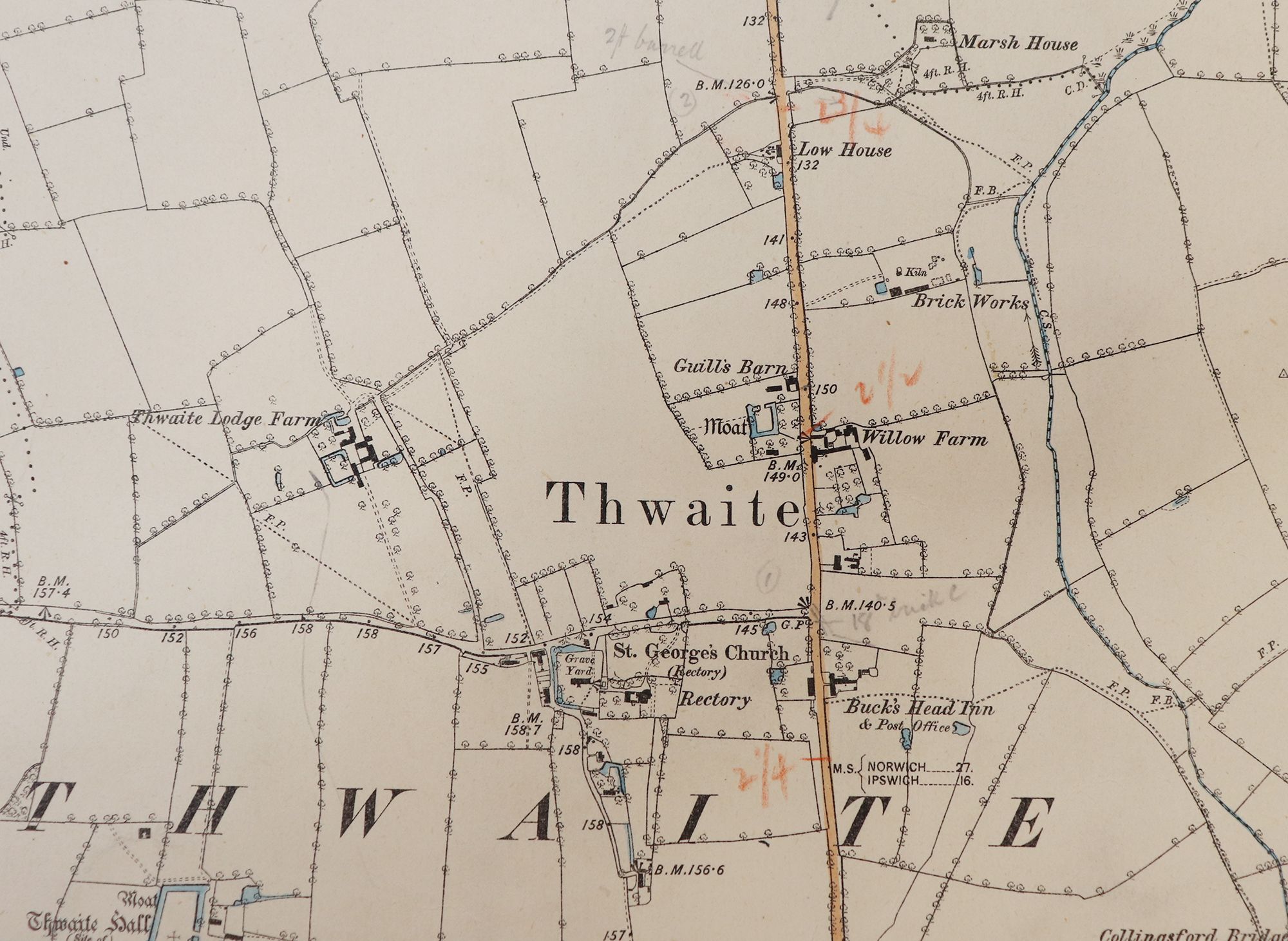

Welcome to Thwaite

Whistlecraft spent almost his whole life in the small village of Thwaite in north Suffolk. In 1841, when Whistlecraft was in his early 30s, it had a population of 176 - slightly more than it does today. It is 5 miles from the nearest town of Eye and sits astride the main road from Norwich through Ipswich to London - now the busy A140. Petty Sessions, which were the court of the local magistrate, were held at the Buck Inn (now the Walnut Tree) once a month on Mondays. They had two cattle fairs, one held on the 30th June, and the other on the 26th November. The small parish church is dedicated to St George; Whistlecraft and his children would have been baptised here. In Whistlecraft’s time, Thwaite would have been a small close-knit community.

Whistlecraft's home, Minerva Cottage, is the first building directly north of the Buck’s Head Inn. The inn would have been a busy coaching inn in Whistlecraft’s day.

Whistlecraft's home, Minerva Cottage, is the first building directly north of the Buck’s Head Inn. The inn would have been a busy coaching inn in Whistlecraft’s day.

Whistlecraft's early years

Orlando was born on 11th November 1810 in the village of Thwaite and was baptised in the small parish church. His father, James Whistlecraft, was a farmer who ran the village shop and also worked as a carpenter. This was the second marriage for his mother, Susan, who was described in an article in the Suffolk and Essex Free Press in 1859 as ‘a notable woman of good judgement and business habit, and her common sense always led her to encourage the studious tendency [in] her youngest child’.

When Orlando was still very young, he contracted rheumatic fever which led to paralysis of his right arm and leg. This meant that he could not follow a career involving manual labour which ruled out following his father into farming or carpentry. He was initially sent to a school in Stowmarket, about 10 miles away, when he was 8. Two years later he was sent to a school near his home which he could walk to. These walks not only improved his health but also inspired him to take an interest in natural phenomena.

After three years his health improved so much that, under his mother’s influence, he was sent to Mr Clamp’s St Nicholas Academy in Ipswich. He made excellent progress - so much that he eventually became an assistant master at the school. In Ipswich, he entered into the intellectual life of the town and joined the local Mechanics Institute which encouraged his interest in nature, especially Meteorology, and the scientific approach.

When he was around 19, Orlando returned to Thwaite and set up a school which ran successfully until 1843. He then ran the local shop providing groceries and stationery. In 1843 he married Elizabeth Rush and set up home in Minerva Cottage next to Orlando’s parents. They had six children, two boys and four girls. Here Orlando could settle down to study meteorology and write his books and newspaper articles whilst attending to his shop.

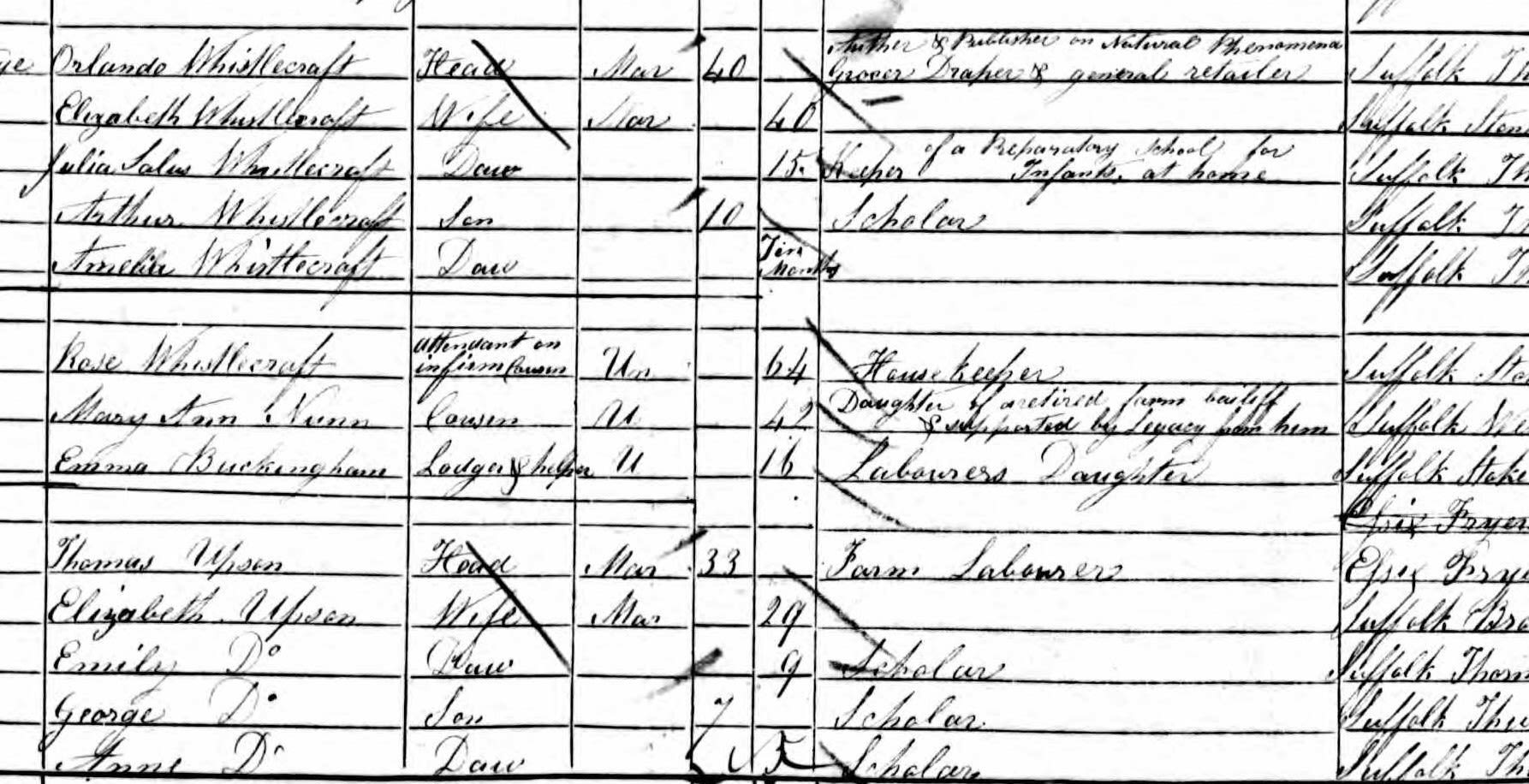

Orlando Whistlecraft and his family recorded on the 1851 census. His occupation is given as 'Author and Publisher on Natural Phenomena. Grocer draper and general retailer.'

Orlando Whistlecraft and his family recorded on the 1851 census. His occupation is given as 'Author and Publisher on Natural Phenomena. Grocer draper and general retailer.'

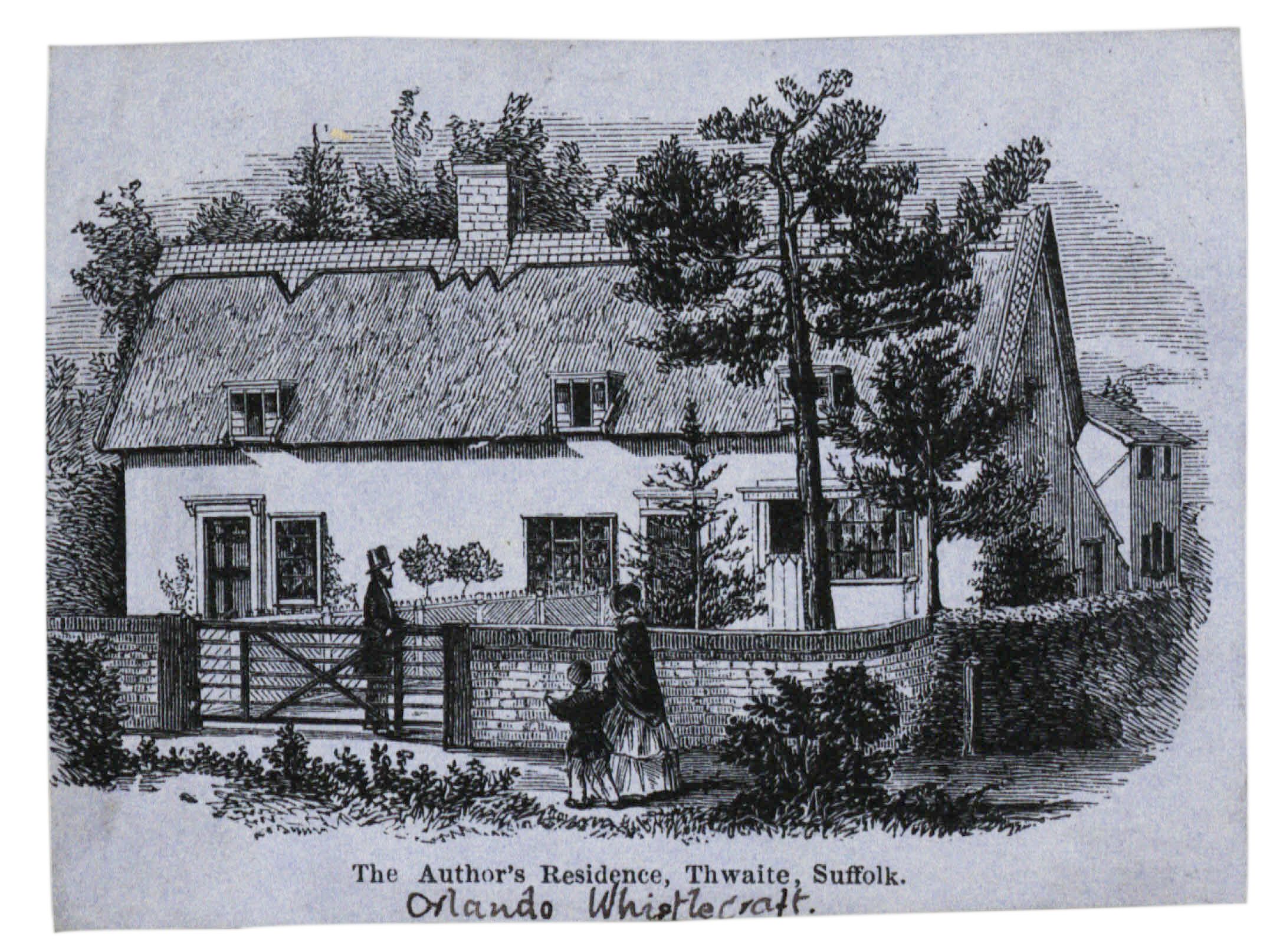

A profile of Orlando published in the Suffolk and Essex Free Press in 1859 described the family's home, Minerva Cottage:

“On the main road between Ipswich and Norwich, just beyond Thwaite Buck’s Head—a famous hostelry in the old coaching days, and still a flourishing roadside inn—there stands a roomy and somewhat rambling edifice which was evidently one time the homestead of a small farm. At one end, the window has been thrown out in the form of a shop-front; beyond the business quarter lies a commodious sitting-room; overhead, two or three dormer windows jut out from the thatched roof; and the large garden in front, laid out in beds with high borders of box, in this time of the year bright with old-fashioned flowers, conspicuous amongst them being luxuriant growth of hardy fuchsias. It is a wonderfully quiet and secluded spot, where the only event of human interest is the passing by of an occasional vehicle.”

The house still stands today, but being on the main road between Ipswich and Norwich sees rather more than an 'occasional vehicle' passing!

Whistlecraft was also a gifted artist - the watercolours below are a series he painted showing his impression of the weather in each month of the year (click to see the full image).

A harvest scene painted by Whistlecraft as a young man - something he would have been very familiar with, having grown up in a rural village

A harvest scene painted by Whistlecraft as a young man - something he would have been very familiar with, having grown up in a rural village

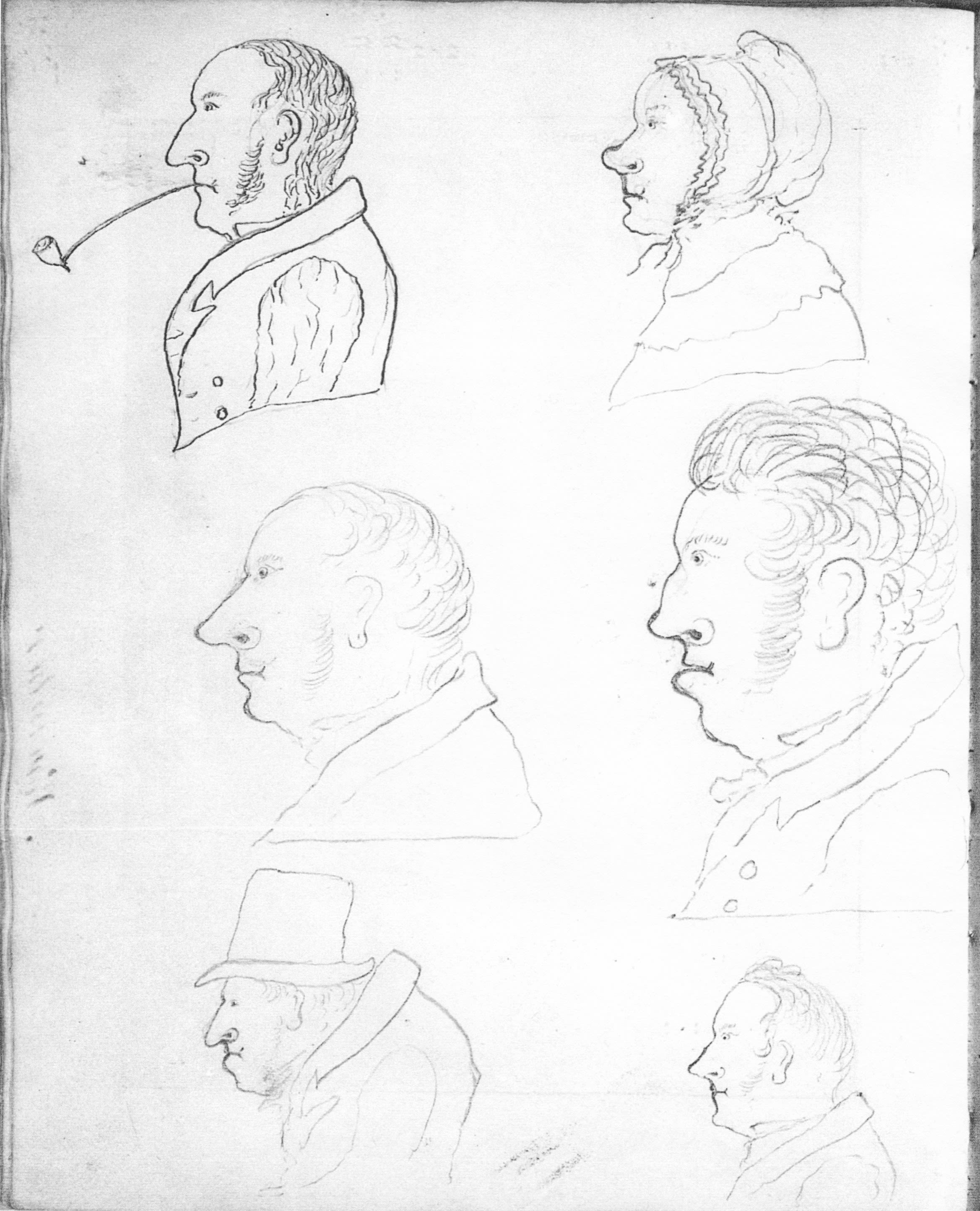

Sketches by Orlando Whistlecraft, likely observing the faces of people he knew or met.

Sketches by Orlando Whistlecraft, likely observing the faces of people he knew or met.

Print of Minerva Cottage, Orlando Whistlecraft's home for many years. It still stands today (PT/419/1)

Print of Minerva Cottage, Orlando Whistlecraft's home for many years. It still stands today (PT/419/1)

'Rejoice, ye farmers!'

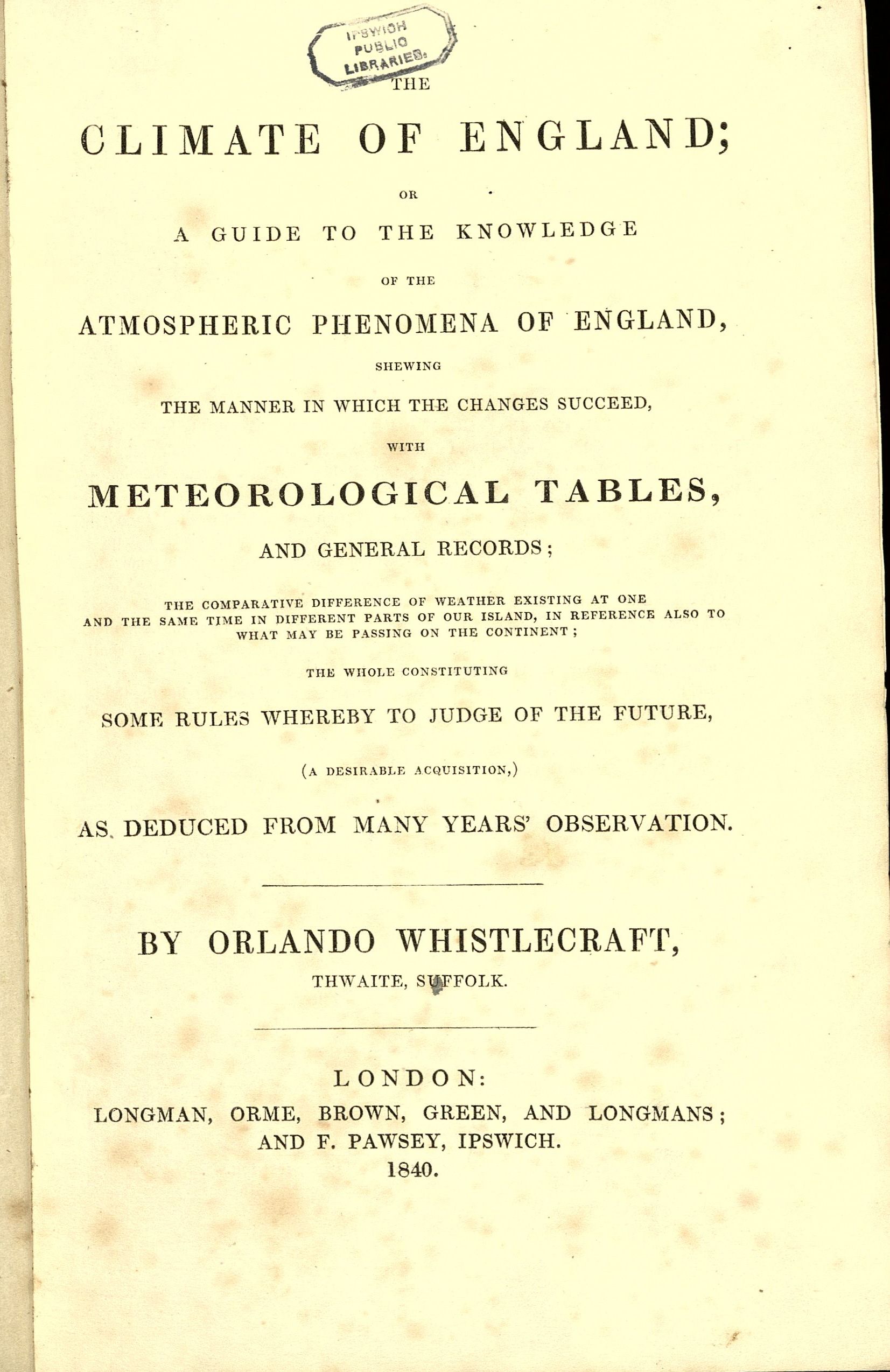

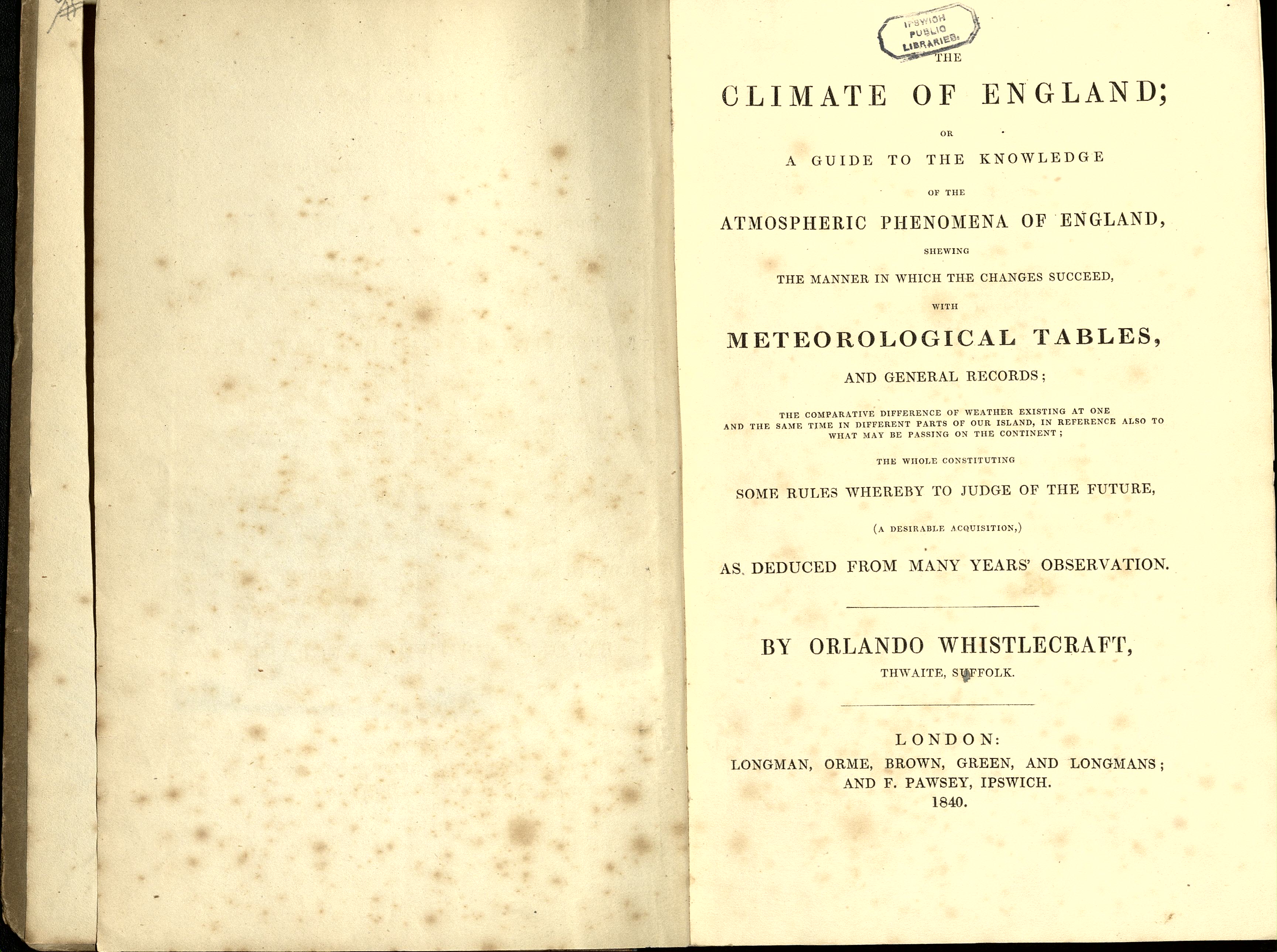

Throughout history, the success of human activities has been closely tied to the weather. In his 1840 book The Climate of England, Whistlecraft described meteorology as ‘the only study which concerns all mankind alike'.

Farming was a particular area of concern for Whistlecraft, with many people's livelihoods in Victorian Suffolk depending on successful harvests. In 1861 he published Meteorology: Its Importance to All Men, Especially Farmers Containing Certain Signs of Coming Weather for The Quarter, Week, Or Day. The title page tells us that it was read to a meeting of the Ipswich Farmers’ Club.

For farmers to decide when best to sow or harvest their crops they need to have a good idea of what the weather is going to be. At the time of sowing crops the soil needs to be warm enough and damp enough to trigger germination. Whilst crops are growing they must have sufficient moisture - but not too much or it will succumb to disease - and sufficient sun to ripen. When crops are harvested it must be dry or there is a danger of the harvest rotting.

Storms can flatten wheat, making it difficult to harvest. This is especially the case when using mechanical harvesters, which were beginning to be used by the end of the nineteenth century. Victorian wheat had much longer stalks than the varieties used today, meaning they were much more susceptible to wind damage. Hay, once cut, had to be left to dry out before being collected into storage.

During Victorian times it was important for farmers to get an idea of what weather to expect so they could plan their activities. If they were about to harvest and a storm had just been predicted, could they complete the harvest before the storm struck or was it better to wait until the storm had cleared and conditions became drier? So, farmers had to become adept at identifying the signs of impending storms.

Farming was a main focus of Whistlecraft's Almanacs and newspaper articles, and he would frequently comment on things like when would be a good time to cut hay or plant seeds.

Mr Constable harvesting in Drinkstone with a horse-drawn cutting machine (K505/2465, courtesy of Bury Past and Present)

Mr Constable harvesting in Drinkstone with a horse-drawn cutting machine (K505/2465, courtesy of Bury Past and Present)

A harvested cornfield (K997/56/16)

A harvested cornfield (K997/56/16)

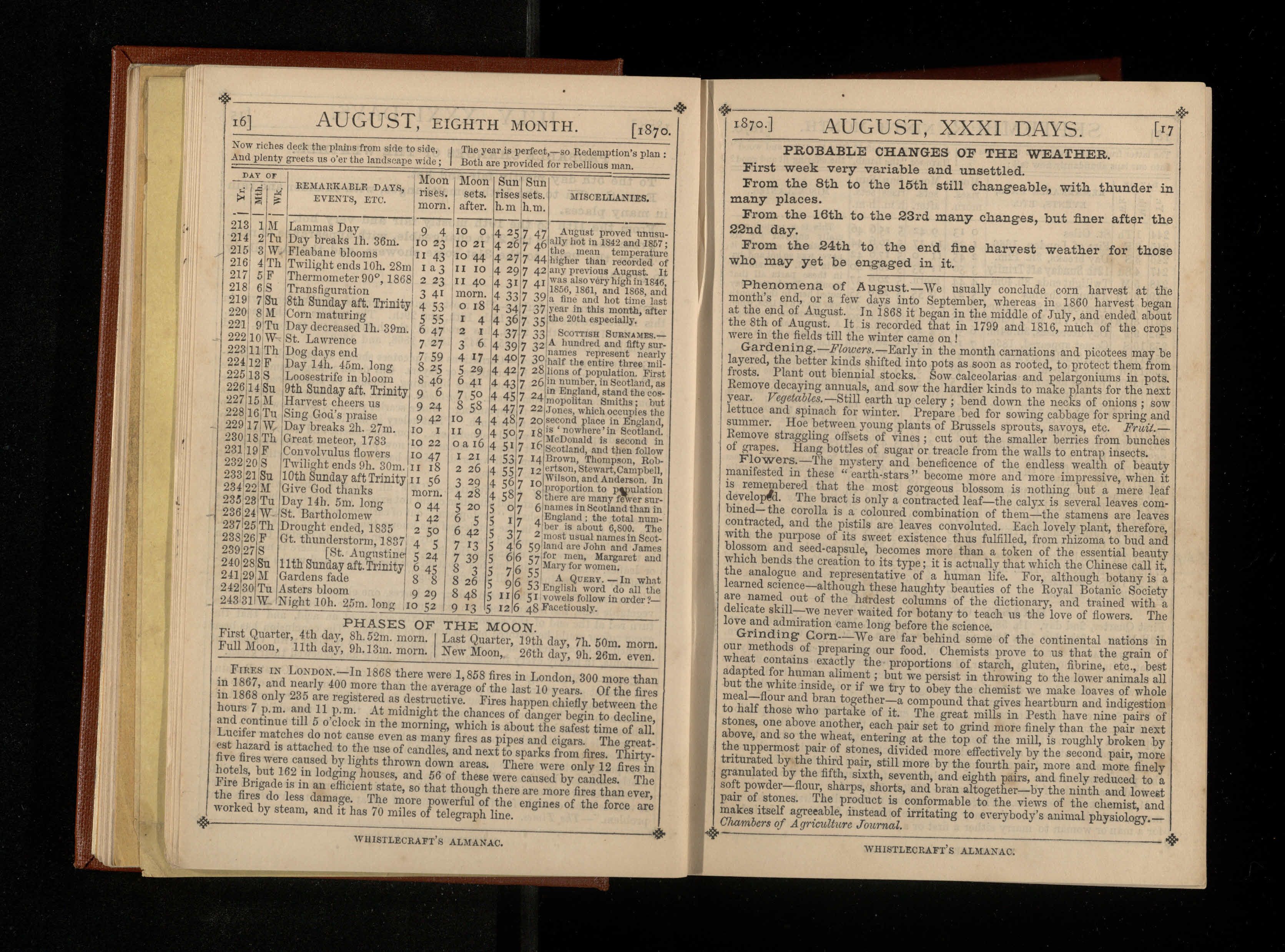

The entry for August in Whistlecraft's Almanac for 1857, with a forecast for overall good weather for harvest, but with some storms

The entry for August in Whistlecraft's Almanac for 1857, with a forecast for overall good weather for harvest, but with some storms

Recording and predicting the Weather

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were a time of great scientific progress. There was great public interest in and discussion of the latest scientific findings. Orlando Whistlecraft, in his time in Ipswich, was caught up in this interest and participated in the wider intellectual discussion. His interest in meteorology and natural phenomena caused him to set up his own programme to record the daily weather and share his results.

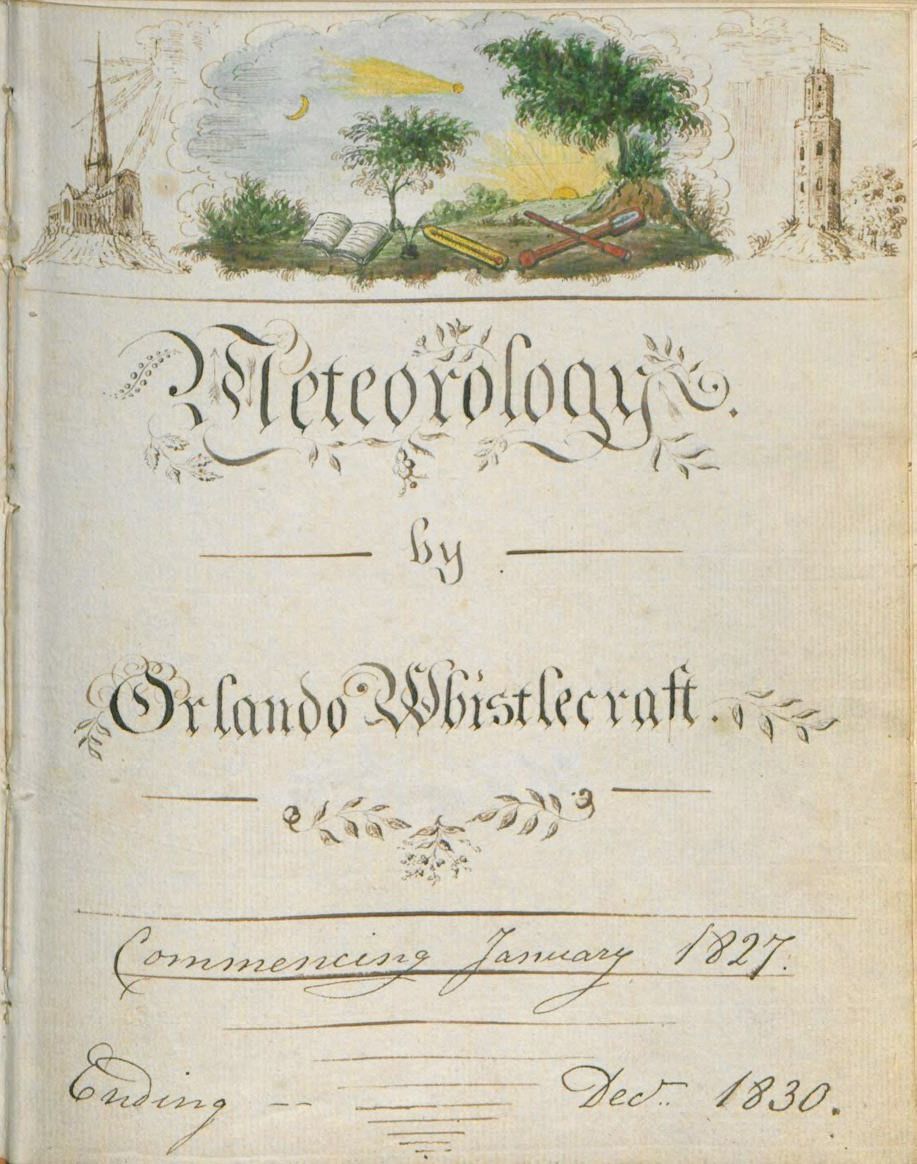

The title page of Orlando Whistlecraft's first weather diary, begun in January 1827, when he would have been about 17 years old. (Courtesy of the National Meteorological Office Library and Archive)

The title page of Orlando Whistlecraft's first weather diary, begun in January 1827, when he would have been about 17 years old. (Courtesy of the National Meteorological Office Library and Archive)

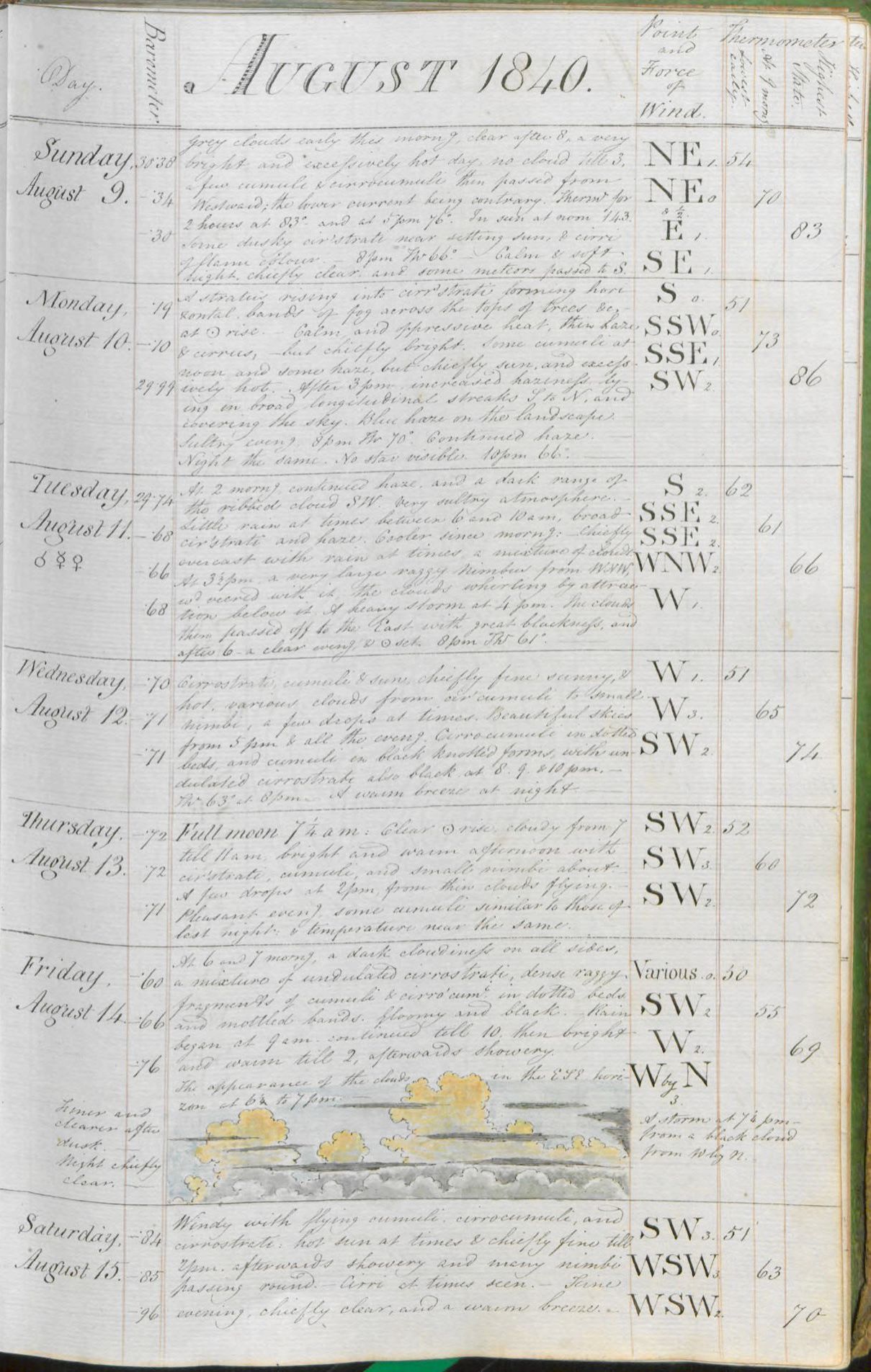

Every day Whistlecraft would go out into his garden at Minerva Cottage and note in a journal what that day’s weather was like. He began this in 1827 at the age of 17, and continued until 1892, shortly before his death at age 82. He would record the maximum and minimum temperatures of the day, rainfall, atmospheric pressure, and the direction and force of the wind. He also wrote little descriptions of the day’s weather, such as:

‘Severe frost and fog all day; wind N. calm. The trees beset with ice. The frosty figures on the inside of the windows continued perfect all day, where a fire was not made.' (Thursday 25th January 1827)

‘Severe lightning and thunder in the west till 9 this morning; having continued 9 hours, the black rocky clouds emitting their fiery darts afforded a grand scene.’ (Monday 20th July 1827)

‘Flying clouds with sun, and boisterous wind in the morning.’ (Monday 31st March 1845)

Over the decades he filled several journals with his observations, which are today looked after by the National Meteorological Office Library and Archive and can be viewed online.

Whistlecraft was not alone in his careful record keeping. The keeping of a weather journal was a popular pastime for the Victorians and some time before that. There is evidence in his journal that he corresponded with other like-minded people across the country. In the flyleaf of his journal covering 1838 to 1844, he has a list of people with whom he corresponds. In particular, he notes in his journal that he first corresponded with Thomas Pallant of Redgrave in 1837 when Whistlecraft would have been 27 and living back at Thwaite, and Pallant would have been 64. Whistlecraft visited Pallant several times a year from 1838 until Pallant died in 1842. He says that Pallant’s Meteorological Journals for 1786 to 1842 were presented to him in 1843. So, there is a sort of network of weather correspondents of which Whistlecraft was a member.

The observations Whistlecraft made in his garden, along with information he gathered from historical sources about weather going back over the previous 200 years, were the basis for his forecasts. He was attempting to identify patterns to predict what was likely to happen in the future.

Whistlecraft's weather records for August 1840. Occasionally he would draw a representation of the weather he had observed, such as the cloudscape on this page (Courtesy of the National Meteorological Office Library and Archive)

Whistlecraft's weather records for August 1840. Occasionally he would draw a representation of the weather he had observed, such as the cloudscape on this page (Courtesy of the National Meteorological Office Library and Archive)

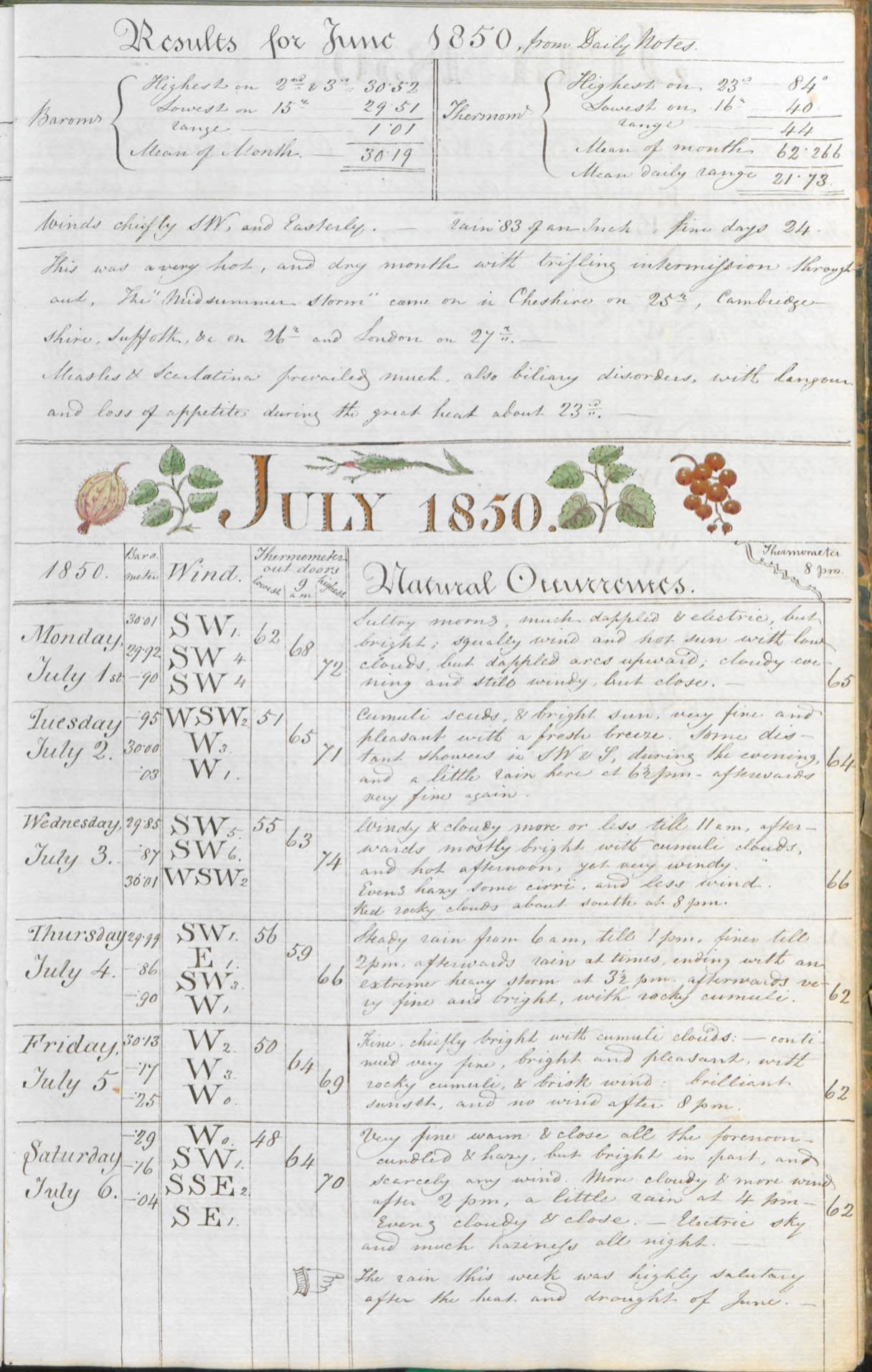

Sometimes Whistlecraft used his artistic skills to decorate the pages of his weather diary with seasonal illustrations such as these summer leaves and berries in July 1850 (Courtesy of the National Meteorological Office Library and Archive)

Sometimes Whistlecraft used his artistic skills to decorate the pages of his weather diary with seasonal illustrations such as these summer leaves and berries in July 1850 (Courtesy of the National Meteorological Office Library and Archive)

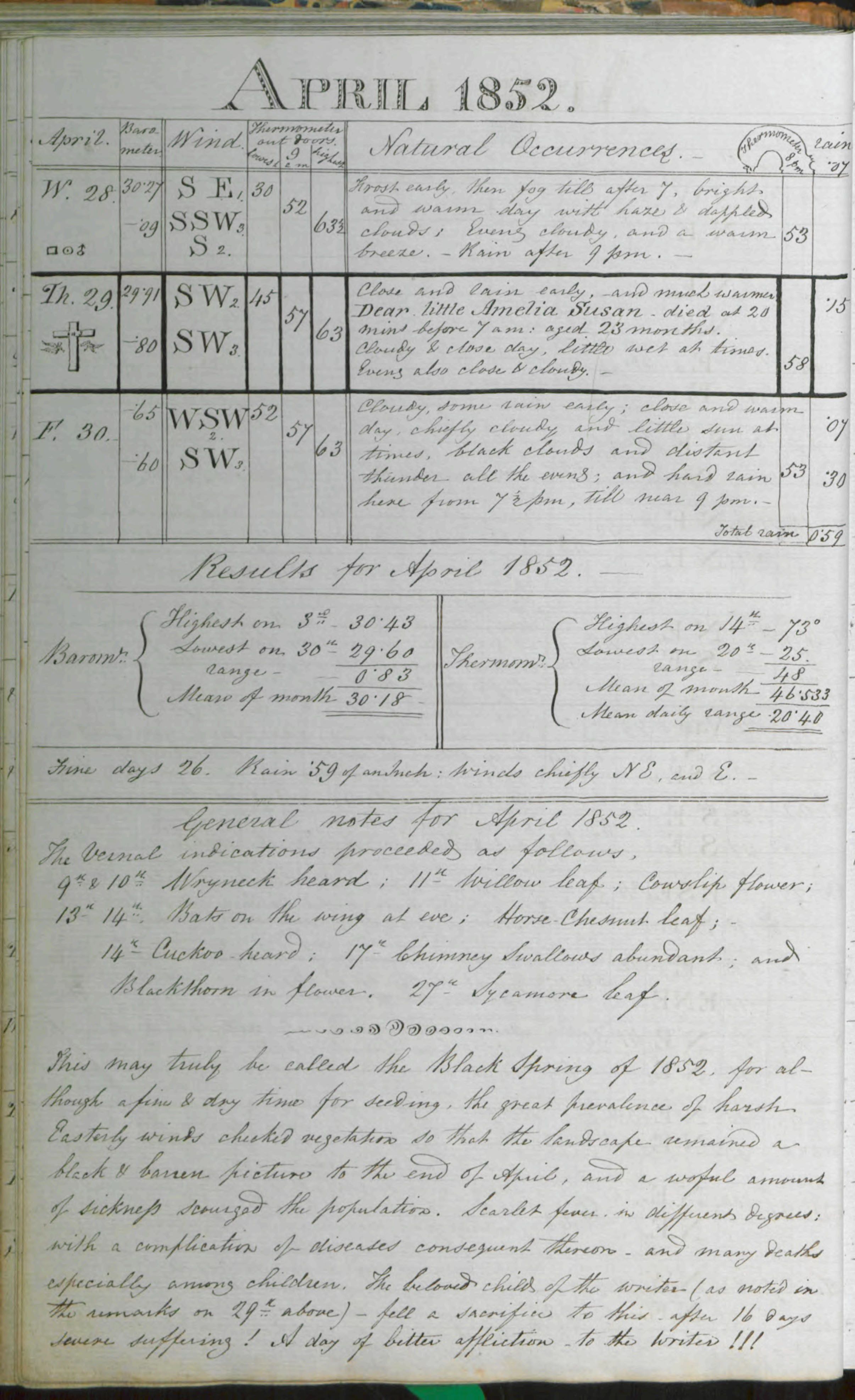

Whistlecraft also noted significant personal events, such as the death of his daughter Amelia Susan in April 1852 (Courtesy of the National Meteorological Office Library and Archive)

Whistlecraft also noted significant personal events, such as the death of his daughter Amelia Susan in April 1852 (Courtesy of the National Meteorological Office Library and Archive)

'What does Whistlecraft say?' Enquire within

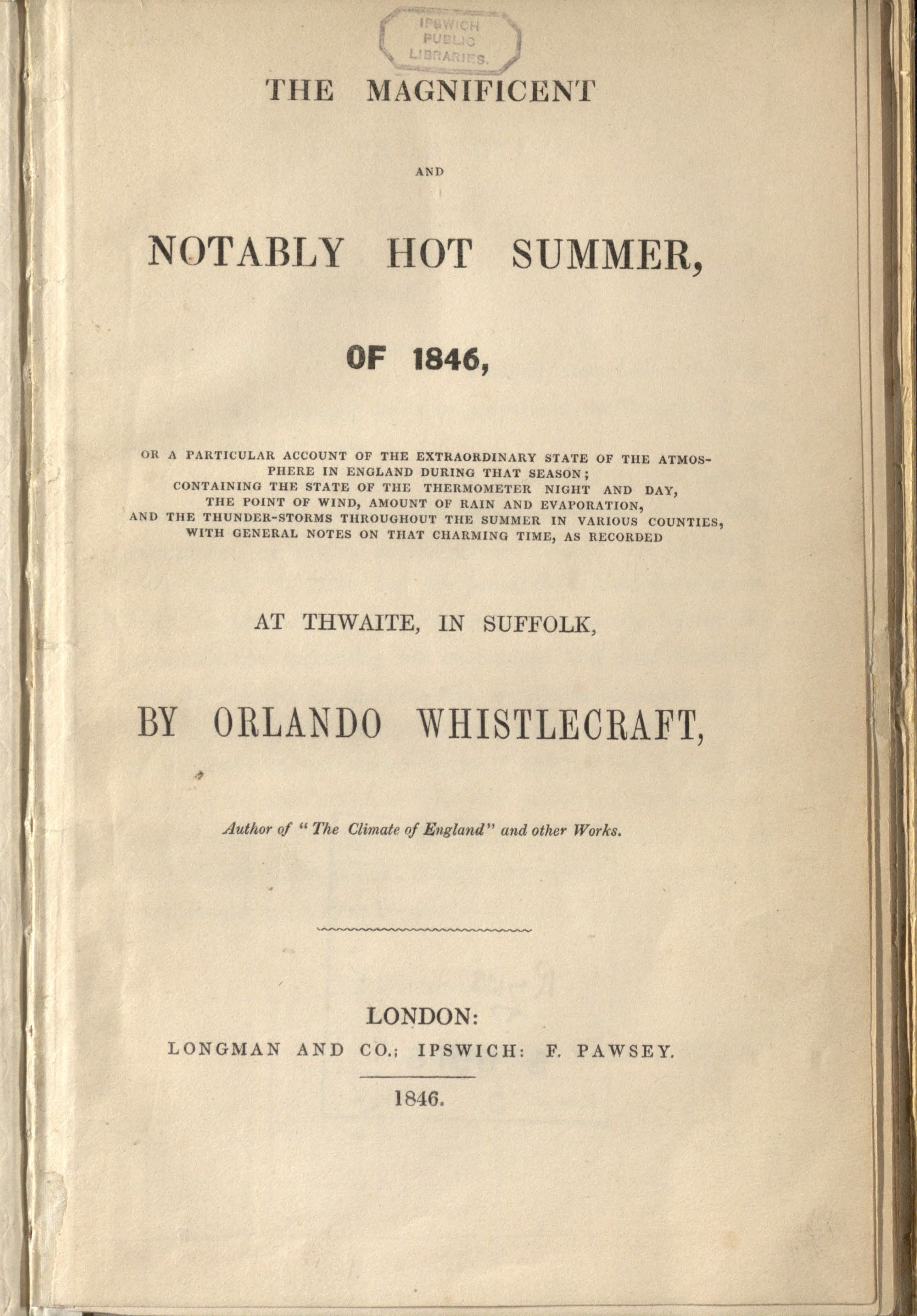

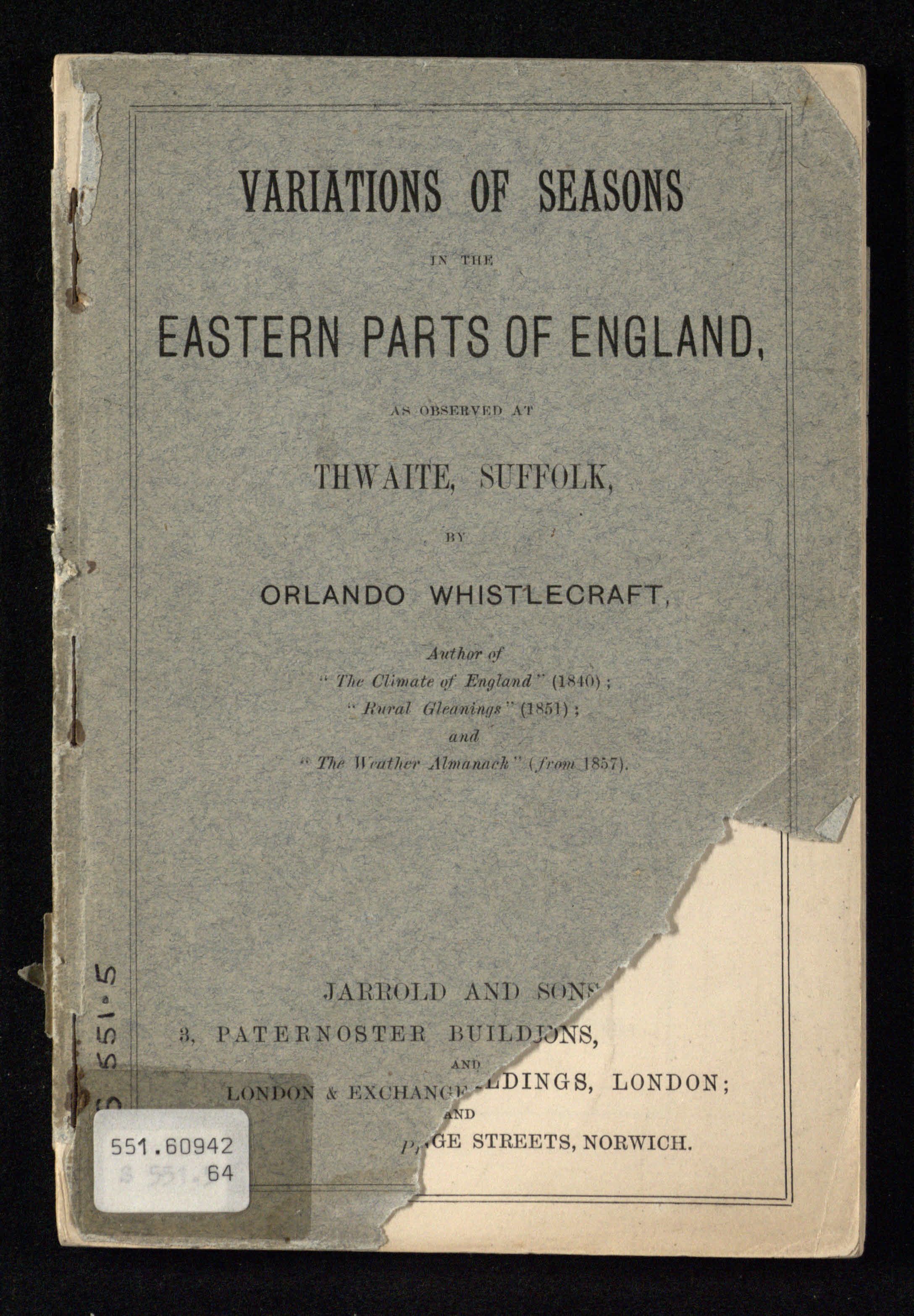

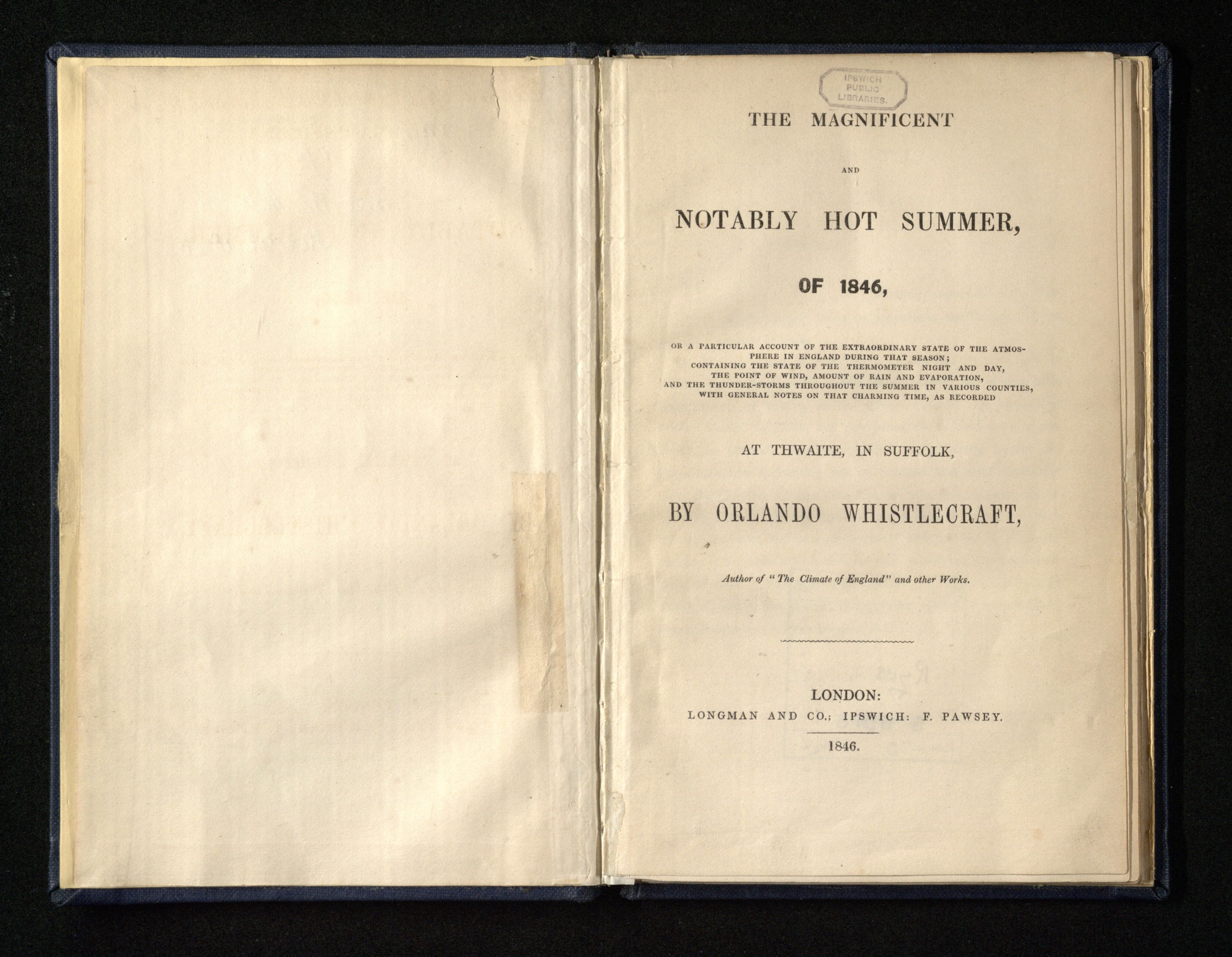

Whistlecraft wanted to share the results of his studies with as many people as possible, in a way that could be widely understood, and he wrote several books explaining his ideas. In his book Rural Gleanings he wrote that his aim in his publications was that ‘our records of daily things should be such as to be read by all, and clearly understood by all, kept in a plain manner, without technical terms, and not as we see them stuck in the periodicals, so as to interest only those who sent them. No, we want regular reports… being put out in a clear and generally interesting form.’

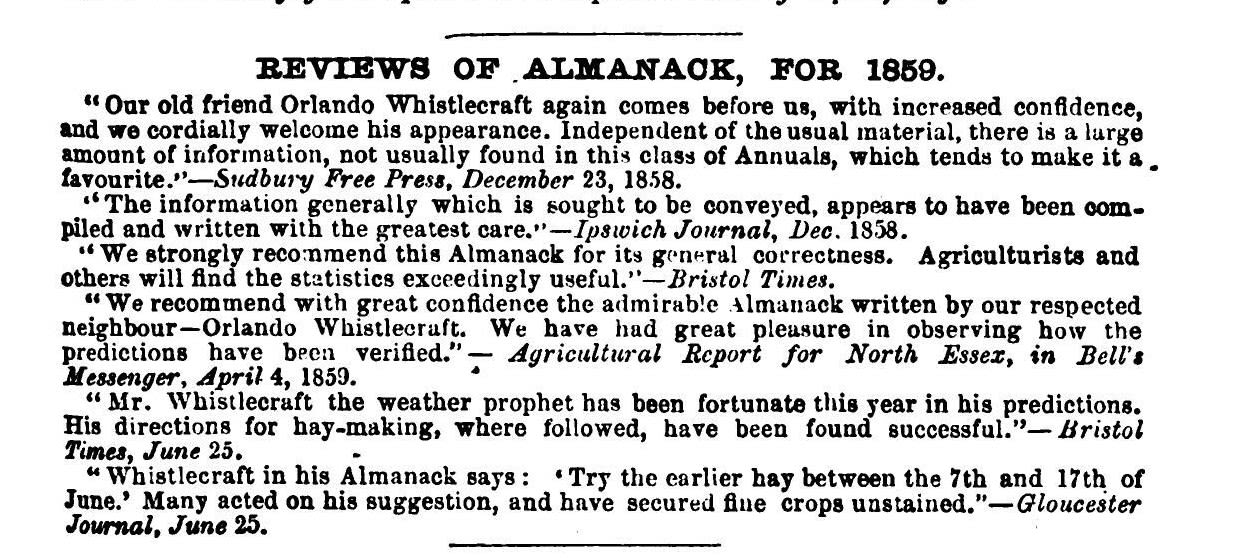

After many years of publishing fortnightly weather forecasts in local newspapers, it was suggested to Whistlecraft that he should write an almanac – a book published every year with useful information about that year, in this case with a focus on forecasting the weather.

His first almanac of 1857, titled simply ‘The Weather Almanac’, was mainly a month-by-month prediction of weather and church festivals, with related topics and came to about 40 pages. The length of Whistlecraft’s almanacs grew steadily over the next 10 years, as he added more information to them, perhaps to increase its general appeal. By 1871 it had grown to over 100 pages, and was titled ‘Whistlecraft’s Almanac Register & Advertiser’.

In the first year the almanac sold between 4,000 and 5,000 copies and the next year 8,000; circulation peaked in 1862 at 10,000.

The main focus of each almanac was the summary of the monthly weather and events for each month of the year. Each month had two pages with the first giving events associated with each day of the month and the rising and setting times of the sun and moon. It also included the phases of the moon. The next page gives the weather predictions for the month and a comparison with the same month in previous years. The almanacs also contain articles and observations on natural history and farming and local information.

With his 12-month forecasts, however, Whistlecraft was attempting to do something extremely difficult, if not impossible, and he had mixed success with the accuracy of his predictions.

Whistlecraft's Almanac of 1860 included praise for previous editions

Whistlecraft's Almanac of 1860 included praise for previous editions

Whistlecraft’s almanacs seem to have been generally well-received, especially amongst the farming community. He continued to publish them every year for 30 years right up to 1886, only five years before his death.

'What does Whistlecraft say?' Enquire within

Whistlecraft wanted to share the results of his studies with as many people as possible, in a way that could be widely understood, and he wrote several books explaining his ideas. In his book Rural Gleanings he wrote that his aim in his publications was that ‘our records of daily things should be such as to be read by all, and clearly understood by all, kept in a plain manner, without technical terms, and not as we see them stuck in the periodicals, so as to interest only those who sent them. No, we want regular reports… being put out in a clear and generally interesting form.’

After many years of publishing fortnightly weather forecasts in local newspapers, it was suggested to Whistlecraft that he should write an almanac – a book published every year with useful information about that year, in this case with a focus on forecasting the weather.

His first almanac of 1857, titled simply ‘The Weather Almanac’, was mainly a month-by-month prediction of weather and church festivals, with related topics and came to about 40 pages. The length of Whistlecraft’s almanacs grew steadily over the next 10 years, as he added more information to them, perhaps to increase its general appeal. By 1871 it had grown to over 100 pages, and was titled ‘Whistlecraft’s Almanac Register & Advertiser’.

In the first year the almanac sold between 4,000 and 5,000 copies and the next year 8,000; circulation peaked in 1862 at 10,000.

The main focus of each almanac was the summary of the monthly weather and events for each month of the year. Each month had two pages with the first giving events associated with each day of the month and the rising and setting times of the sun and moon. It also included the phases of the moon. The next page gives the weather predictions for the month and a comparison with the same month in previous years. The almanacs also contain articles and observations on natural history and farming and local information.

With his 12-month forecasts, however, Whistlecraft was attempting to do something extremely difficult, if not impossible, and he had mixed success with the accuracy of his predictions.

Whistlecraft's Almanac of 1860 included praise for previous editions

Whistlecraft's Almanac of 1860 included praise for previous editions

Whistlecraft’s almanacs seem to have been generally well-received, especially amongst the farming community. He continued to publish them every year for 30 years right up to 1886, only five years before his death.Writing is a medium of communication that represents language through the inscription of signs and symbols.

In most languages, writing is a complement to speech or spoken language. Writing is not a language but a form of technology. Within a language system, writing relies on many of the same structures as speech, such as vocabulary, grammar and semantics, with the added dependency of a system of signs or symbols, usually in the form of a formal alphabet. The result of writing is generally called text, and the recipient of text is called a reader. Motivations for writing include publication, storytelling, correspondence and diary. Writing has been instrumental in keeping history, dissemination of knowledge through the media and the formation of legal systems.

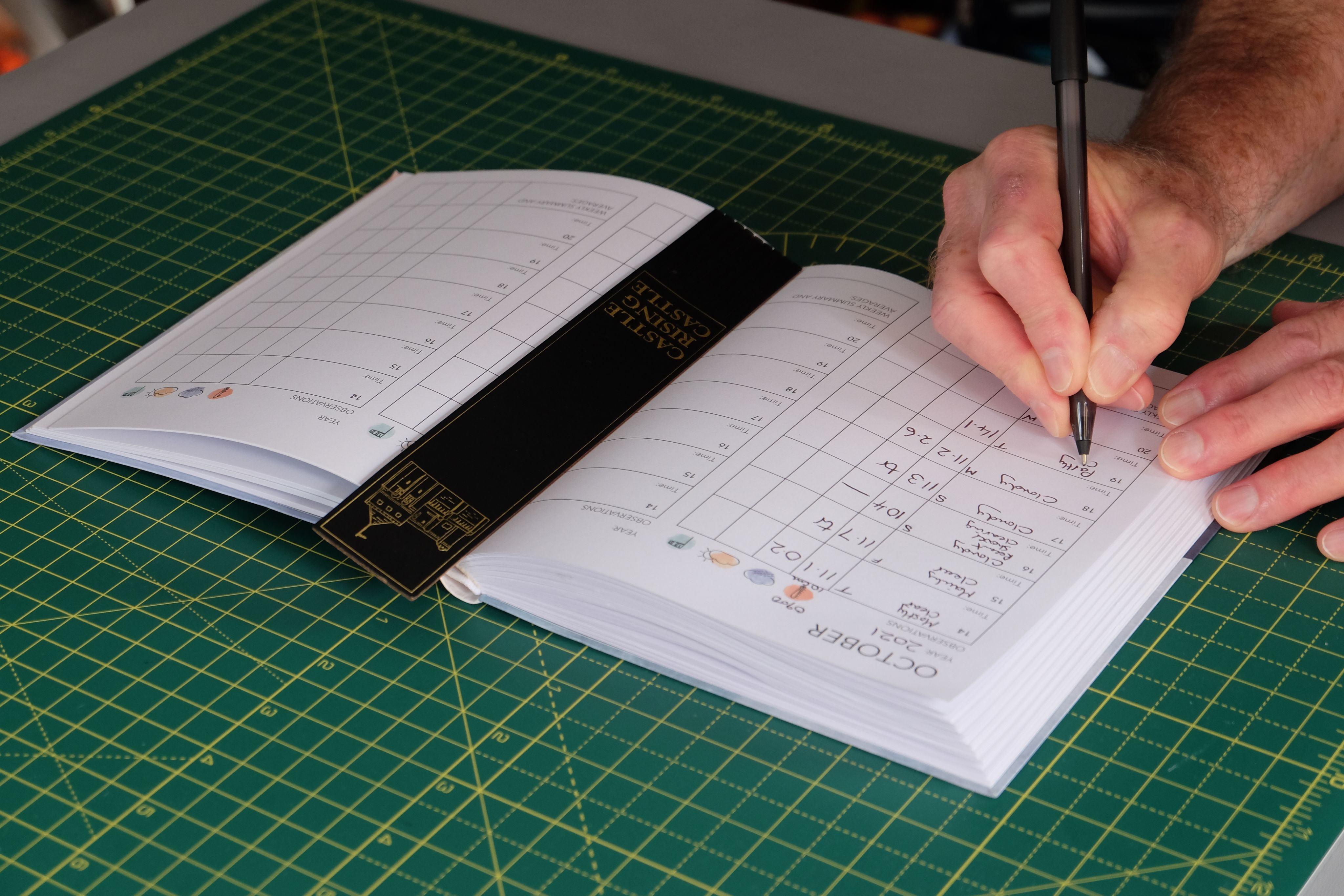

Today's Whistlecrafts

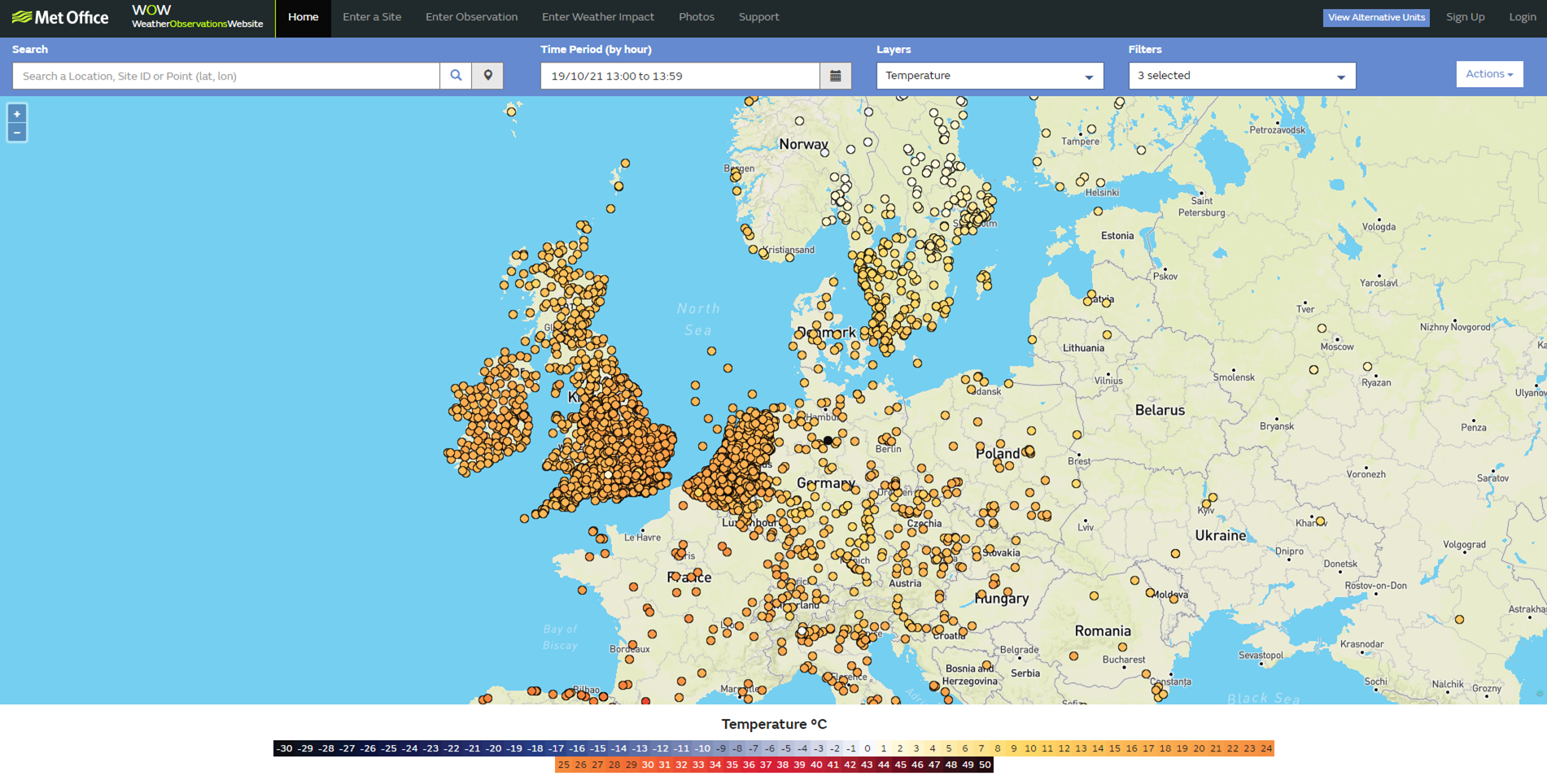

Today, weather enthusiasts across the country - and around the world - play a hugely important role in recording weather data which are used to compile forecasts.

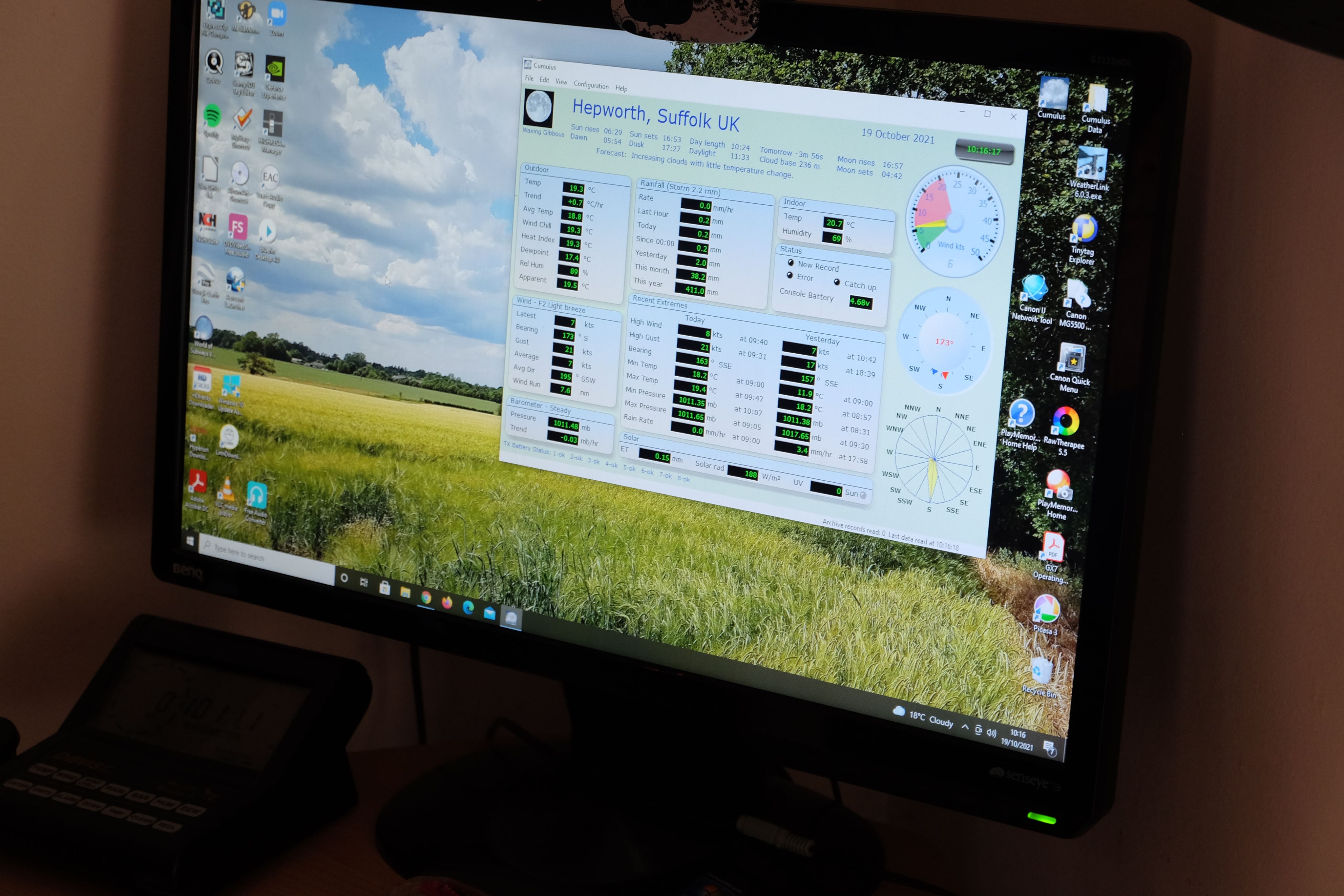

Just like Whistlecraft, these citizen scientists keep daily records of their local weather. Unlike Whistlecraft, their data can be automatically fed into online databases, and used by the Met Office to help monitor, record, and predict the weather.

One modern Whistlecraft is Richard Hinton, who has been recording weather data in his garden in Hepworth, a few miles west of Whistlecraft's home in Thwaite, since 2007.

“I became interested in recording the weather at the age of 10, during the hot, sunny summer of 1959. My Dad gave me an old greenhouse max/min thermometer which I hung under a tree in the garden, in the shade. I was fascinated to see how high it would go during the day. A few years later in the winter of 1962/3, I was doing the same thing, this time seeing how low it had been during the night, under deep snow cover. Since then, I have always taken an interest in recording the weather, wherever I have lived.”

Richard Hinton in his garden with his weather station. This measures temperature, humidity, and more.

Richard Hinton in his garden with his weather station. This measures temperature, humidity, and more.

An anemometer measures windspeed and direction (powered by a solar panel). The strongest gusts Richard has ever recorded were 80mph.

Sometimes the old tools are still the best – Richard takes a daily rainfall reading. Rain is collected in a glass container which is inside a copper sleeve and set into the ground.

A measuring container shows how much rain has fallen in the last 24 hours – in this case 2.6 millimetres.

This thermometer is set into the earth to record the ground temperature, providing very useful information for gardeners.

While most measurements are taken by automated instruments and the data are fed straight into a computer, for rainfall, ground temperature and cloud cover Richard records the data manually.

Readings from the weather station in Richard’s garden feed directly into online databases.

These data being collected everyday at weather stations across the world feed into online networks such as the Met Office's Weather Observation Site. Visit the site to find your nearest weather station.

Then and now

As part of this project we have compared Orlando Whistlecraft's weather data from the 1870s with data recorded in the 2010s by Richard, a few miles away from Thwaite in Hepworth.

This comparison has shown us that in the last 10 years we have experienced far more days with temperatures of 30 degrees centigrade or above than Whistlecraft did in the 1870s. Days where temperatures were recorded of 0 degrees centigrade or below, meanwhile, have drastically dropped.

Comparing the average maximum temperatures from the 1870s to the 2010s we can see that average temperatures have increased by around 1.5 degrees C.

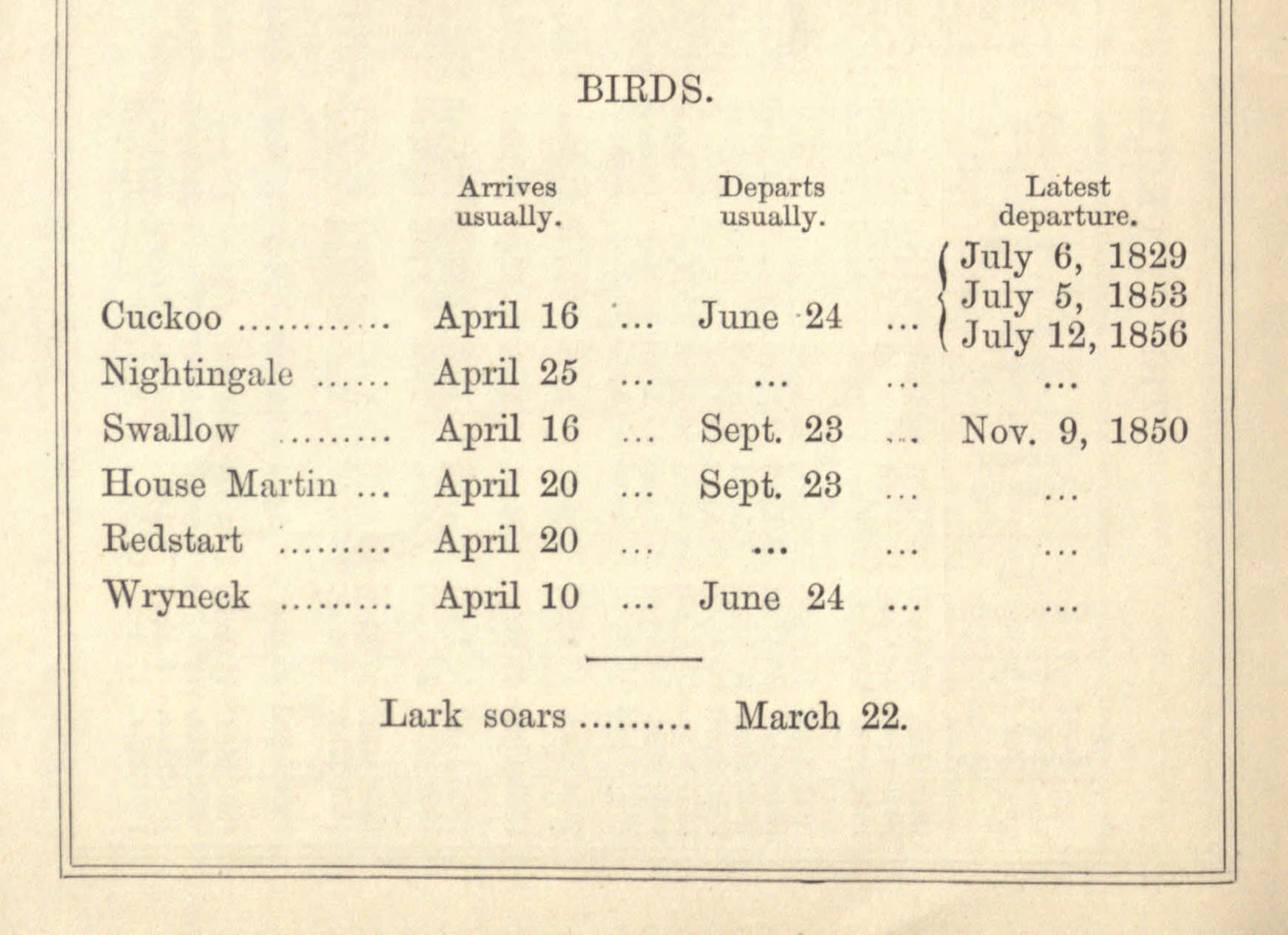

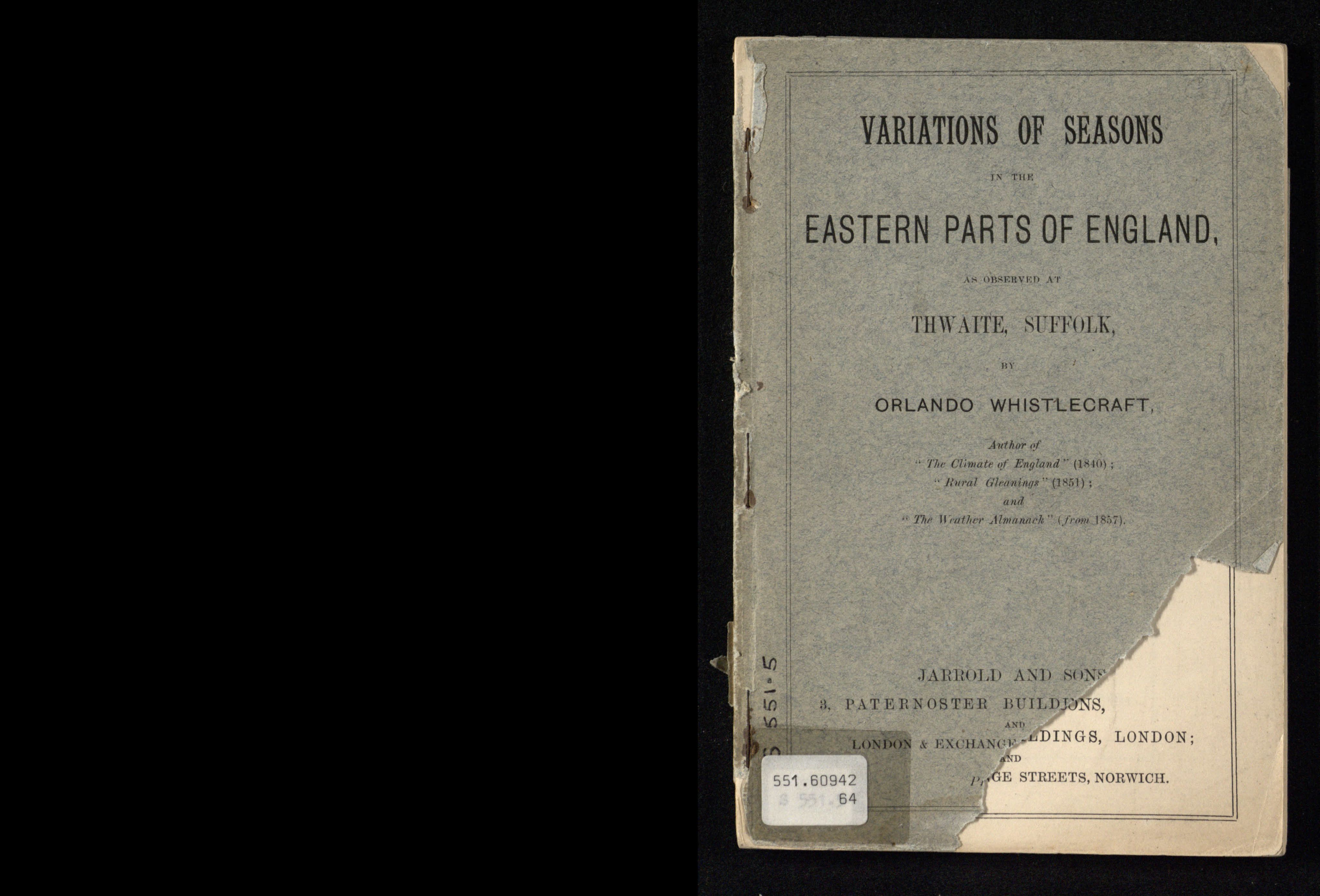

Whistlecraft also kept records of events in the natural world, which help us today to see how seasonal events are changing. In his book Variation of Seasons (1883), he included a table showing the usual arrival dates for various migratory birds.

Comparing Whistlecraft's data to recent records indicates that birds usually arrive rather earlier than they used to when Whistlecraft was observing*:

- Cuckoos: Whistlecraft noticed Cuckoos arriving around April 16th, they now appear on average a week or so earlier – average 9th April

- Nightingales: have shifted their average arrival time from 25th April to 12th April

- Swallows: in Whistlecraft’s time Swallows arrived around 16th April and now appear a month or so earlier – average 17th March

The Redstart is now very rare as a breeding bird in Suffolk and the Wryneck has not bred here since 1972.

*The dates and changes noted cannot be more than indications as it is not clear precisely what Whistlecraft means by 'first arrival date'. It could be the average date in a year when the first of a bird species was seen, or it could be when bigger groups arrived. It is also not clear as to exactly what period is being considered. The modern figures are specifically the average date of the first sighting of a species in Suffolk from 2011 to 2020 inclusive with dates as published in the Suffolk Bird Report for each year.

Whistlecraft's observations of when migratory birds would usually arrive, from Variations of Seasons, 1883

Whistlecraft's observations of when migratory birds would usually arrive, from Variations of Seasons, 1883

From the past to the future

It is thanks to the work of Orlando Whistlecraft and others like him that scientists today are able to make comparisons between the weather of the past and present, and track how our climate is changing.

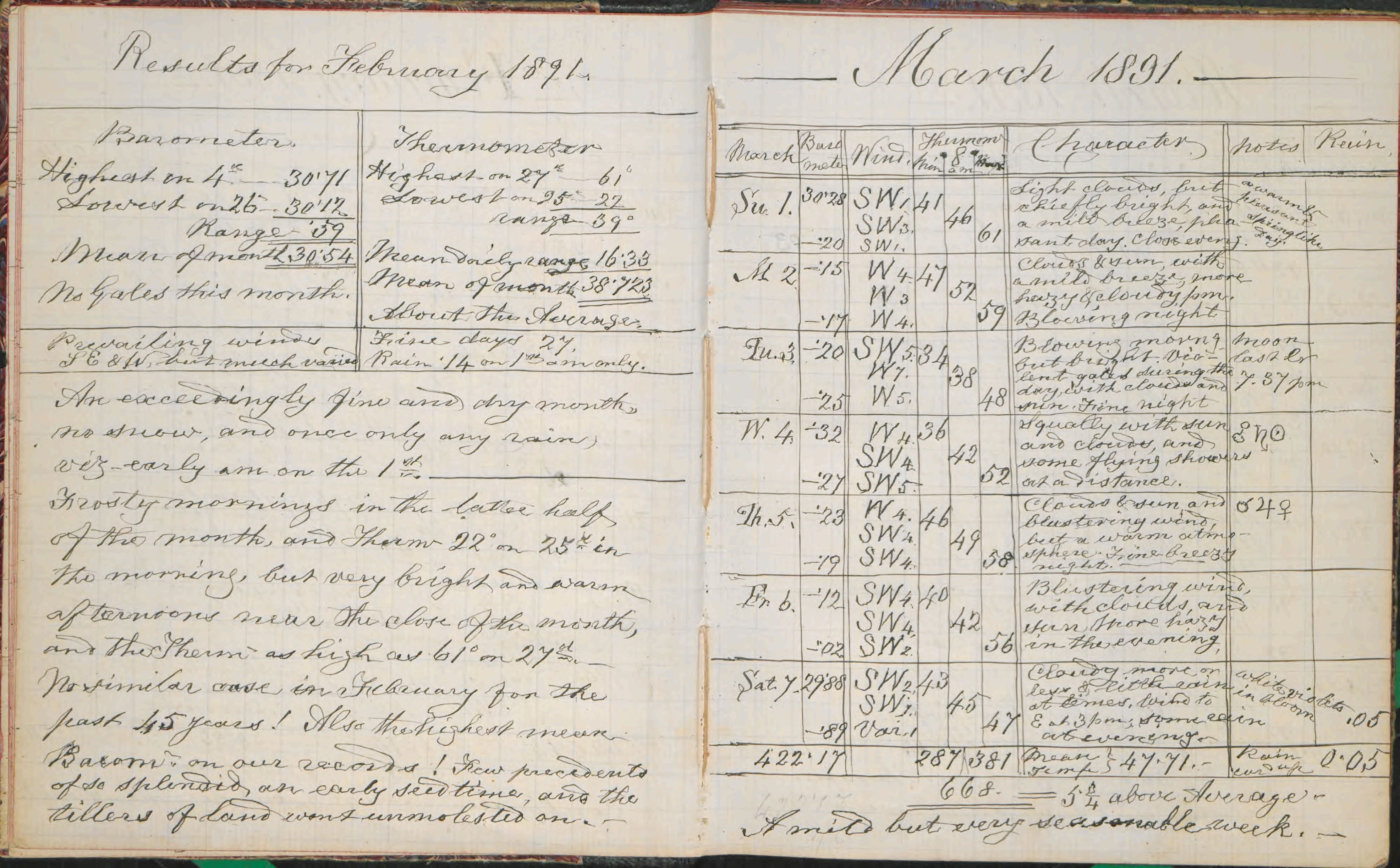

Whistlecraft continued his work almost to his dying day. He lived to the grand age of 83, and continued to live at Minerva Cottage and record the weather. These entries in his weather diary, painstakingly made by a weakening hand, were made when he was 81 years old.

Orlando Whistlecraft's weather journal for March 1891 (Information provided by the National Meteorological Library and Archive – Met Office, UK.)

Orlando Whistlecraft's weather journal for March 1891 (Information provided by the National Meteorological Library and Archive – Met Office, UK.)

Despite having enjoyed some degree of local fame in his life, Whistlecraft fell onto harder times in old age. Appeals were published in the East Anglian Daily Times for people to donate money to enable him to live a little more comfortably.

Just four months before he died, Whistlecraft was interviewed by a journalist from the East Anglian Daily Times. He had broken a leg a few months earlier and was confined to his bed when he was interviewed:

‘Sitting upright under the canopy of a four-poster bedstead, warmly and comfortably clad, was the venerable man, who had on his knees before him a large manuscript book in which he was writing… all round and about the age-stricken occupant there was evidence of complete absorption in work well-loved’.

The journalist obviously looked on Whistlecraft with some reverence and affection, and describes him as a pioneering scientist:

‘His forecasts were based upon patient and persevering observations natural phenomena; he made no pretension to occult knowledge; he was, in fact, one of the pioneers of the modem science or system of meteorology’

Whistlecraft attempted to predict the weather for each coming year at a time, but scientists today make much longer-range predictions. To find out what the weather might look like in the future in your local area, try out the BBC’s climate visualisation tool.

Learning about how our climate is changing can be alarming; Imperial College London has some suggestions for actions which can help to combat climate change in their resource ‘9 things you can do about climate change’.

Minerva Cottage - Orlando Whistlecraft's home for many years - as it looks today

Minerva Cottage - Orlando Whistlecraft's home for many years - as it looks today

![Watercolour drawing of a hay wain going out through a gate to a barn to collect the harvest. A man stands on the road with a pitchfork over his shoulder and two other men in the Haywain also with pitchforks. In the distance is a field containing heaps of corn sheaves [stooks]. Handwritten caption “Maturity of Corn – off for another load; all hands ahoy or August from nature”](./assets/h0nEI8c9qb/8-august-1047x781.jpeg)

![Watercolour scene of a hay wain going out through a gate to a barn to collect the harvest. A man stands on the road with a pitchfork over his shoulder and two other men in the Haywain also with pitchforks. In the distance is a field containing heaps of corn sheaves [stooks]. Handwritten caption “Maturity of Corn – off for another load; all hands ahoy or August from nature”](./assets/UXEF4BH5qM/8-august-1047x781.jpeg)