Soil Sisters: Putting the Women's Land Army on the Map in Suffolk

Soil Sisters is a Sharing Suffolk Stories project - part of a family of projects accompanying the creation of The Hold, a brand new archive centre for Suffolk.

This display has been created by Suffolk Archives volunteers, with support from staff, and brings together some of the things they have found most interesting during their research.

The display is accompanied by an interactive map which you can also visit to explore local Land Army stories. If you have a story you would like to submit to the project, please contact us on sharing.suffolk.stories@suffolk.gov.uk

Where the project began...

Nicky Reynolds has been an avid collector of Women’s Land Army ephemera and uniforms for over twenty-five years. Several years ago, she met Vicky Abbott, who has been collecting for over ten years, and the two combined their collections to put on a display at a show in Norfolk. They stood back and looked at their display and realised that, between them, they had quite an impressive amount of Women’s Land Army history. They spoke about how it would be gratifying to do something worthwhile with it, and to perhaps even look into their own home county of Suffolk to further discover the role the women played locally.

Nicky took an interest in the Land Army at a very young age and can even remember dressing as a Land Girl in a carnival. She met her husband, Nick, who was interested in military history and keen to support Nicky’s interest in the Land Army. Similarly, Vicky’s former partner was an avid military collector who encouraged her interest in women’s roles during the war. She also grew up on a farm and so felt a certain affiliation with the Land Girls. Nicky and Vicky both have family members who served, which has further encouraged their interest.

Soon after their conversation, by chance Nicky saw an advert for The Hold, the new Suffolk Archives building in Ipswich. She learnt that, thanks to the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Suffolk Archives was supporting a variety of local projects whose aim was to encourage people to learn about Suffolk’s heritage in new and exciting ways. She and Vicky jumped on this idea and submitted a proposal which would include interviewing women in Suffolk who had served in the Land Army – now in their 90s – and also researching those who were, sadly, no longer with us. It would also look at the infrastructure behind the organisation and discover how Suffolk helped to contribute at a national level. The idea was to ultimately create a virtual map of the county, accessible to all, containing details of Land Army anecdotes and facts in the form of photographs, videos and audio recordings.

Since having their proposal accepted, Nicky and Vicky, along with a team of dedicated volunteers, have thrown themselves into gathering information from all corners of the county – attending historical events, launching appeals on the radio and via newspapers, travelling to visit former training camps and hostels, visiting museums and archives round the country, and chatting to anybody who would care to listen about the project! It has been a journey of discovery and one that will continue to develop as more information is uncovered about Suffolk’s Land Girls.

Nicky Reynolds, left and Vicky Abbot, right, who proposed the Soil Sisters Sharing Suffolk Stories project

Nicky Reynolds, left and Vicky Abbot, right, who proposed the Soil Sisters Sharing Suffolk Stories project

Adjusting to life in the Land Army

After joining the Women’s Land Army, new recruits would be sent anywhere that they were needed.

For many this was a big adjustment; in a 2019 interview one former Land Girl described how she felt when arriving at her new home at the WLA hostel in Lakenheath:

'we'd never been in the country before, we'd never left home before... the first day we went I think we all cried, we kept saying as the planes were going across please take us home!'

Not only were women like this young recruit living away from home for the first time, for many it was their first experience of the countryside and their first experience of agricultural work. For those living in hostels, there was also the adjustment to communal living and a lack of privacy.

The new recruits had to quickly adapt to hard physical work. In this clip our former Lakenheath Land Girl describes what a typical day looked like for her:

Life in Land Army hostels

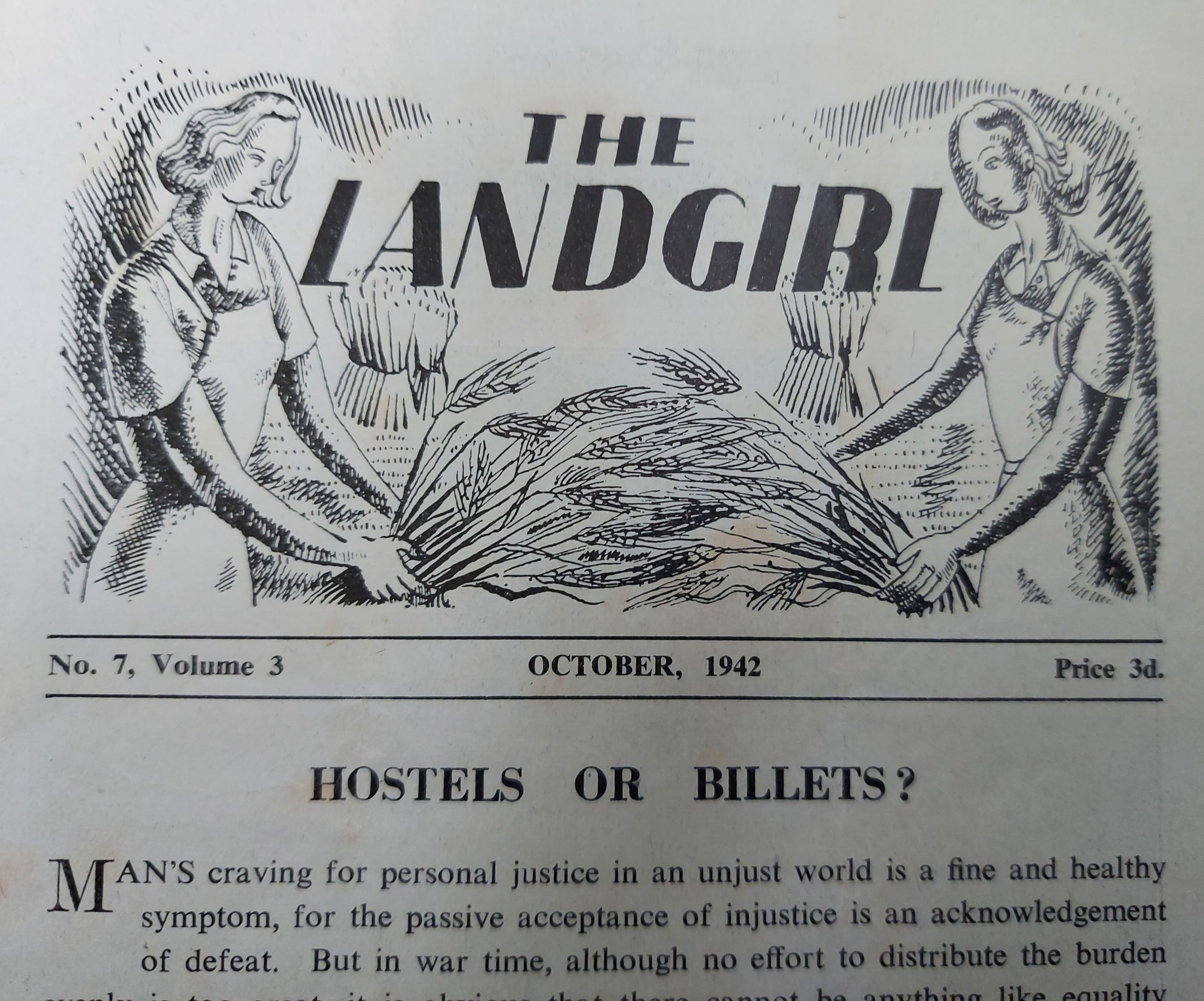

The front of the October 1942 edition of The Land Girl magazine asked the question “Hostels or Billets?”. Margaret Pyke (the editor) then went on to describe the relative peace and quiet afforded by being housed in a billet, compared to the ‘greater opportunities for community life and amusement’ (in other words, a social life!) provided by the hostels.

With East Suffolk opening its first hostel to thirty girls, a warden and helpers at Blomvyle Hall in Hacheston on 26th January 1942, the county was set to join other parts of the country who, at the end of 1941, had already begun to house their girls in this way. A shortage of workers in agriculture meant that gangs of Land Girls were required in Suffolk, and hostels became a necessity in which to accommodate them.

Prior to the opening of hostels, Land Girls had been housed individually or in small numbers in billets – these were often farmer’s cottages or cottages of people in the village. Whether or not they were happy in their lodgings often depended upon the attitudes of the people with whom they had to live. Unfortunately, there are numerous stories of cruelty afforded to them, such as not being allowed to dry their wet clothes in front of the fire before wearing them to work the following day. Many of the girls also came from the towns and cities, so being billeted in accommodation in the middle of the countryside, often with no electricity or running water, came as a shock.

With the arrival of hostels came a more structured, stable and sociable environment for the girls. Many of these hostels were existing buildings, such as halls or rectories (examples being Oak Lawn in Hoxne and The Old Rectory in Campsea Ashe), which were requisitioned by the Ministry of Works who then adapted and furnished the houses to make them fit for purpose. Of course, hostels were not always such grand abodes; there were also converted stable blocks and purpose-built hutments that accommodated the gangs of land girls.

By May 1942, West Suffolk could boast that it had housed as many as 116 girls at a new purpose-built hostel in Lakenheath, which was run by the Y. W. C. A. and was to become the biggest hostel in England. One former Land Girl who resided there remembered in an interview in 2019 that there were two larger dormitories and a third smaller one, with ablutions serving each. She describes each dormitory as being divided into cubicles for four girls – containing bunks, dressing tables, and a wardrobe for every individual. Her lasting memory is of having to get used to there being very little privacy as there were no doors on the cubicles. On one occasion, she took a trip home and then returned to the hostel to find that somebody had gone into her wardrobe and borrowed her dress without her permission! Similarly, despite labelling all their clothes, it was not unknown for things to go ‘missing’ on occasions, particularly after they had been washed in one of the sinks and then left to air in the drying room.

A former resident shares her memories of the WLA hostel at Lakenheath

Not all hostels had large dormitories divided into cubicles – at the Rectory in Halesworth, the girls slept six to a room. There were also sleeping quarters for the staff who looked after them – wardens, domestics and cooks. There was a common room, in which the girls could spend their recreational time (often gathering around a stove for warmth), and a kitchen in which the cooks prepared the meals each day.

The women’s days were structured. They had to be up early each morning so that they could have breakfast before being collected, normally by a lorry, and taken to whichever farm the gang was working on that day. They would go wherever the War Agricultural Executive Committee decided they were needed. If they were working away from their hostel then the cook would provide them with a packed lunch, often consisting of a sandwich or meat pie and fruit, along with a Thermos flask containing a hot drink. For those who did not have flasks but were working near a farmhouse, arrangements would be made for tea to be supplied. After a day’s work, the women would be taken back to their hostel for their evening meal and recreation time. The warden would ensure that all the women were in bed at an allotted time, with lights out, although at certain times of the year (such as harvest), the women were required to work overtime.

Having limited availability during the earlier part of the war, hostels were seen as a privilege. The Land Girl magazine stated that the girls living in them were encouraged to ‘make their hostel a centre for all members of the Land Army in the area, and they should also remember that their particular privileges have duties attached’. The girls certainly did remember this and arranged much entertainment for those billeted in the neighbourhood, including dances, whist drives, tea parties, and more. The land girls were young and, for many, this was their first time away from home. With the threat of invasion hanging over them, and having worked so hard during the day, many grasped the opportunity to have a good time. There was added excitement for those located in hostels close to airfields occupied by the RAF and the USAAF, as they were often invited to attend dances – transport was even sent to collect the girls. Stephen Palmer, whose mother was from Hull and was based at Lakenheath, commented that “if it wasn’t for land army girls, half the men in Lakenheath would have been single!”.

Who was in charge?

Lady Gertrude (or Trudie) Denman was the Director of the WLA. A woman in many ways ahead of her time, she had previously been involved in the campaign for women’s suffrage, and had been Assistant Honorary Director of the WLA in the First World War.

Lady Denman resigned from her position on February 16, 1945 because her efforts to have the WLA receive better pay and benefits after the war were being ignored by the government. WLA and Lumber Jills finally received their well-deserved recognition July 2008, when the government stated that they were giving official medals to them for their service.

Below the national administration, each county had a Chair and a Secretary (there were two of each in Suffolk, the county then being split into East and West).

The Chair of the West Suffolk WLA was Lady Grace Briscoe, a medical doctor who had worked in an RAF laboratory during the First World War, before focusing on women's health. She moved to Lakenheath in 1930, where she served as a Justice for the Peace and campaigned for the introduction of women police officers. In the post-war years she made a significant contribution to archaeological investigations in Suffolk.

County Secretaries received a modest salary and an allowance of petrol coupons to allow them to fulfil their duties. The women who took on this role were usually financially well-off and socially well-connected.

In East Suffolk, this role was filled by Ethel Sunderland-Taylor. When the 1939 Register was taken just before the outbreak of war, she was living at Culpho End in Culpho, with her husband Ralf, who was a solicitor. Her occupation was initially recorded as ‘unpaid domestic duties’, but later changed to ‘Secretary East Suffolk L[and] A[rmy]’.

This former Land Girl recalled how, like the national WLA Director Lady Gertrude Denman, Mrs Sunderland-Taylor resigned in disgust when WLA members did not receive any official recognition at the end of the war:

Every army needs a uniform

The Women’s Land Army uniform seems very formal and old fashioned in the 21st century but the clothing they were issued was very practical for the hard work that the women had to do in all weathers.

A new Land Army recruit could expect to be issued with:

A badge

2 pairs corduroy breeches

1 long sleeved cotton poplin shirt

1 V-neck dark green pullover

1 brown felt hat

The brown felt hat was intended to be worn as shown in the top image above. However, this was a fairly out-of-date look for the time, and many WLA members chose to reshape their hats in the 'pork pie' style shown in the second image.

The brown felt hat was intended to be worn as shown in the top image above. However, this was a fairly out-of-date look for the time, and many WLA members chose to reshape their hats in the 'pork pie' style shown in the second image.

2 aertex short sleeved shirts

2 pairs dungarees

1 oilskin or rubberised cotton mackintosh

Later in the war this was changed to a Melton wool overcoat

2 cotton drill overall coats

6 pairs woollen socks (also called stockings)

1 pair black leather ankle boots

1 pair brown leather shoes

The shoes were made specially for the Women's Land Army. They had steel toe caps and are marked with 'WLA' on the soles.

The shoes were made specially for the Women's Land Army. They had steel toe caps and are marked with 'WLA' on the soles.

Listen from 40 seconds to hear what Audrey thought of her shoes

1 pair rubber gumboots

The distribution of uniform did not always go smoothly:

‘They sent me a uniform, and of course they sent me two left feet!’

Although the uniform was “free”, the girls had to give 36 of their clothing coupons to get it when they joined and after that, 10 coupons per year. If available, WLA members could buy extra items such as the WLA tie, a dark green windcheater or gloves. Second-hand uniform was sometimes for sale.

The Land Army girls came from many different backgrounds and areas of the country. The uniform was a leveller to make them feel that they were “All in it together”. The girls were not supposed to add personal touches like adding colourful ribbons to the hat. The sight of Women’s Land Army members in uniform also helped to promote the organisation.

As the war went on, both clothing and materials became hard to come by. The Land Girl magazine often printed tips on repairing uniform. Items could be renewed after a year (or six months for the woollen stockings) but the owner had to prove the clothing or footwear was worn out by sending it in for inspection by the Uniform Department.

Gumboots (wellies) were much needed for working long hours on wet land through the winter and were often in short supply. Leather boots or shoes could be waterproofed with mixture of beeswax and oil.

On joining the Land Army recruits received a green armlet. They could sew on a red half diamond for every 6 months of service. Different coloured armlets were given out according to years of service:

- 2 years – green armlet with red piping and 2 red diamonds

- 4 years – red armlet with 4 green diamonds

- 6 years – yellow armlet with 6 green diamonds

- 8 years – green & yellow armlet with a crown and red diamonds

Members of the WLA could take proficiency tests in the type of work they were doing such as horticulture or milking. They were awarded proficiency badges to wear on their uniform if they passed.

A small number of women served for ten years from 1939 until the WLA stopped recruiting in 1949. They were awarded a metal and enamel ten years’ service badge.

Earlier in the war, members leaving the Women’s Land Army were made to hand back all their uniform. Later they were allowed to keep 1 shirt, their shoes and an overcoat. Their overcoats were handed in and a blue or green version was returned to them.

Dangerous Work

The Women’s Land Army took on much work that was traditionally viewed as men’s work. Much of their work was physically hard and there were many potential hazards. In certain parts of the country Land Girls even came under fire from enemy aircraft while working in the fields.

Hazards included:

- Tools and machinery

- Unpredictable livestock

- Chemical spills

- Sunburn or frostbite

- Rat and insect bites

- Heavy lifting and falls

- Blistered hands or feet

- Industrial diseases such as dermatitis or tenosynovitis (a condition that affects the tendons, causing swelling and pain)

The women could be more at risk if they were over tired, hungry or thirsty or unwell.

Members of the Timber Corps were paid more than Land Army women who worked on farms or in horticulture because the work was considered more dangerous. This was often a source of tension between working women.

Ipswich War Memorial

Ipswich War Memorial

Edna Girling's name and organisation on the memorial

Edna Girling's name and organisation on the memorial

Land Girl Edna Girling from Ipswich was killed in a farm accident on 27th January 1943. She was only 17 years old. The inquest into her death revealed that she suffered a broken neck when a baling machine accidentally began to operate and caught Edna's long hair, drawing her into it. She is remembered on the War Memorial in Christchurch Park, Ipswich.

'The funeral of Miss Edna Girling (Women's Land Army), of 37, Swinburne Road, Ipswich, who was accidentally killed at Halesworth, took place at Witton yesterday... Lady Cranworth represented the East Suffolk Women's Land Army and East Suffolk War Agricultural Executive Committee... wreaths were sent by Women's Land Army (Halesworth)'

Find out more:

Land Girls at Leisure

The amount of time off that Land girls got could vary a great deal. Those living in Land Army hostels usually worked a half-day on Saturdays and had Sundays off. It was different for the women living on farms who might only get one weekend off per month. Cows, after all, need to be milked twice a day every day of the year. At harvest time Land Army members could be expected to work all the hours of daylight.

It was not until 1943 that Land Girls had the legal right to one week’s holiday per year with full pay. In contrast, women in the armed forces were given 4 weeks paid leave per year.

Land Girls taking a break at during their time working at Columbine Hall in Stowupland

Land Girls taking a break at during their time working at Columbine Hall in Stowupland

Land Army girls were generally young and healthy but they were expected to do long hours of hard physical work for the war effort. Late nights were strictly for weekends and holidays because the girls needed enough sleep to enable them to do their work. Those who showed signs of burning the candle at both ends were likely to be reprimanded.

Although the work of the Women’s Land Army could be tough, the girls found plenty of ways to have fun in their time off. Suffolk Army and Air Force bases were keen for Land Army members to attend their dances and often provided transport.

A Lakenheath Land Girl describes attending a dance with her future husband

Land Girls and British soldiers at a dance near the Women's Land Army forestry training camp at Culford, Suffolk, May 1943

Land Girls and British soldiers at a dance near the Women's Land Army forestry training camp at Culford, Suffolk, May 1943

Although there was no television, Land Girls might occasionally get the chance to go to the cinema. Land Army clubs were set up by the WLA authorities, aimed to be within cycling distance where the girls could go on Saturdays to socialise and relax.

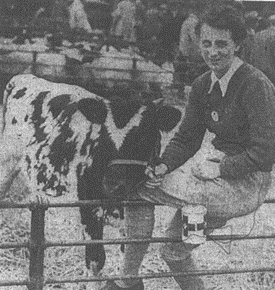

Farm work mixed with leisure time when Land Girls entered ploughing or milking competitions. Land Girls could compete at agricultural shows by entering stock they had raised.

'V-headed calf at Ipswich raises £118 for Red Cross', Suffolk Chronicle, October 1942

'V-headed calf at Ipswich raises £118 for Red Cross', Suffolk Chronicle, October 1942

Sometimes the women had opportunities to attend talks or classes on topics such as health and beauty, handicrafts or cookery. Readers of “The Land Girl” magazine might get creative and spend time doing drawings or writing poems or stories that might get published.

Sports were popular too. Women based at Kirton formed a netball team and a table tennis tournament was held in Bury St Edmunds.

Quizzes with an agricultural theme were held between different Land Army hostels, such as Lady Briscoe's Cup held in West Suffolk.

The team which won Lady Briscoe's Cup at an agricultural quiz in West Sufolk, Land Girl Magazine, August 1946

The team which won Lady Briscoe's Cup at an agricultural quiz in West Sufolk, Land Girl Magazine, August 1946

The WLA hostel at Lakenheath even had its own beauty pageants. One of these was reported in the Bury Free Press on 15th August 1947, when Miss Olive Wakefield was chosen as ‘Miss Lakenheath 1947’. An airman from RAF Lakenheath, Danny Crowe, won the surprise competition of ‘The most handsome man present’. Two German Prisoners of War had helped out with the arrangements by providing decorations.

People were encouraged to do whatever they could for the war effort and a lot of time was spent on fun ways of fundraising:

- Dances – men from local air force and army bases came along as dancing partners

- Tea parties, held indoors, or garden parties depending on the time of year

- Whist drives – a card game competition that people paid to enter

- Stage productions – Land Girls put on concerts and pantomimes

- Handicraft and sales – knitted, sewn and other handmade items were sold especially before Christmas when people were looking for gifts

At all these events, more money could be raised by selling refreshments and holding a raffle. Raffle prizes were very different from today. You might win 100 cigarettes or an orange!

In the early years of the war, Land Army fundraising went towards the Spitfire Fund. After the WLA Benevolent Fund was set up in 1942 this became the focus for the Land Girls’ money-raising efforts.

A Lakenheath Land Girl remembers wearing a scarf to work which covered rollers in her hair, so that her hair would be done by the evening.

The Lumber Jills

The Lumber Jills (officially the Women’s Timber Corps from 1942) were a part of the Women’s Land Army who replaced men from the forestry industry who had been called up for military service. Just like the Land Girls, the Lumber Jills fulfilled a need of wartime Britain. Britain had relied on Norway for much of its timber supply, but when Norway fell to the Nazis the government had to turn to home grown timber – and to women to fell and process it.

The Women’s Timber Corps had the same uniform as the Women’s Land Army, with the exception of a green beret instead of a brown felt hat, and their own badge.

Women's Timber Corps green beret

Women's Timber Corps green beret

Women's Timber Corps bakelite badge

Women's Timber Corps bakelite badge

There was a rivalry amongst the Lumber Jills and the Land Girls, with Land Girls feeling the Lumber Jills were treated better. One of the issues was wages. Once the Land Girls were at their placements, one of the important issues they fought for was pay equality with male agricultural workers. The men earned 38 shillings a week, and the minimum wage for a week of work by a Land Girl was 28 shillings. Lumber Jills were paid more, around 35-46 shillings per week.

Suffolk was home to a large contingent of the Women’s Timber Corps, based at Culford Camp near Thetford, where all new recruits were sent for training.

Vera Howson, of the Women's Timber Corps, with an axe over her shoulder. (Imperial War Museum)

Vera Howson, of the Women's Timber Corps, with an axe over her shoulder. (Imperial War Museum)

Lumber Jills stack pit props in a clearing as part of their training at the WLA forestry camp at Culford. These props were to be used in the coal mines. (Imperial War Museum)

Lumber Jills stack pit props in a clearing as part of their training at the WLA forestry camp at Culford. These props were to be used in the coal mines. (Imperial War Museum)

Some Lumber Jills did additional training to specialise in measuring, costing and invoicing. This picture shows women sitting an exam as part of their training at Culford. (Imperial War Museum)

Some Lumber Jills did additional training to specialise in measuring, costing and invoicing. This picture shows women sitting an exam as part of their training at Culford. (Imperial War Museum)

Grace Eveline Launt (Suffolk Archives)

Grace Eveline Launt (Suffolk Archives)

Later photograph of the cottage where Grace stayed (Suffolk Archives)

Later photograph of the cottage where Grace stayed (Suffolk Archives)

‘The first night I went to bed, I remember thinking ‘what have I done?’ Even more so when the first Lancaster bombers flew over the cottage on their way to Germany, returning at dawn! So much for being safe in the country! It was a nightmare at times.’

Grace Launt working with poultry at Blunts Hall, Little Wratting, Suffolk (Suffolk Archives)

Grace Launt working with poultry at Blunts Hall, Little Wratting, Suffolk (Suffolk Archives)

Grace Eveline Launt

Grace Launt was a member of the Women’s Land Army in Haverhill, Suffolk, in 1941. She wrote an account of her time living and working in Suffolk, which are now held at Suffolk Archives in Bury St Edmunds.

Whilst growing up in Sheffield Grace spent much of her early years involved in the brownies and the Girl Guides. She had always wanted to be a private secretary, and after leaving school aged 16, she worked at Lilywhites sports outfitters alongside studying Pitman’s shorthand, typing, and business methods at night school.

As ‘the clouds of war loomed’, both men and women were called to work, and Grace's boss suggested she join the Women’s Land Army, her parents believing she would be safer in the country. Grace applied, along with her close friend, and on 19 May 1941, they were posted to Dash End, Kedington, Nr Haverhill, Suffolk. Grace’s WLA number was 40878.

‘My boss, who was already an officer in the Sherwood Foresters regiment, suggested the Women's Land Army and my parents agreed, thinking I would be safer in the country. As it turned out, I was in more danger.’

In her written account, Grace described her accommodation, which from the outside looked like a ‘lovely thatched cottage’. When she went inside, though, she ‘came down to earth with a bump’ as the cottage had no bathroom, no electricity, and no carpet. She also remembered feeling scared and unsafe in her first few days, especially when she could hear the Lancaster Bombers flying overhead. However, the food was ‘exceptionally good’, as the two girls received extra rations as well as rabbits and chickens to eat.

Grace’s main responsibility within the Women’s Land Army was to take care of almost 1000 hens, which included feeding them and letting them in and out of their pens early in the morning and late at night. She enjoyed her work very much, ‘especially collecting buckets of eggs’ which then had to be washed and packed for distribution centres. When Grace got hungry, she used to eat raw eggs, and said that most eggs would be in transport for up to 6 weeks before reaching people’s doors, joking that ‘there was no Mrs Edwina Curry about in those days!’

After several months of living as a Land Girl in Suffolk, Grace’s father became terminally ill and she sadly applied for permission to leave the Land Army to help her parents at home. She quickly began working for the ministry of supply, where her typing skills came in handy, and married her fiancé Ronald Dorling in December 1941.

Vivian Broad

Vivian Broad was a member of the Women's Land Army in Suffolk for five years. Although she worked long hours doing hard and sometimes dangerous tasks, she 'thoroughly enjoyed' her time as a Land Girl.

Vivian Broad in her Land Army uniform, aged around 21 years old

Vivian Broad in her Land Army uniform, aged around 21 years old

Vivian joined the Land Army in 1941 and worked for her great uncle, James Davy Sayer, who owned three farms in Suffolk, at Lackford, Wordwell and Herringswell. There were two other Land Girls already working for him, and worried that they would think she was being favoured, she worked ‘extra hard just in case’! While Vivian originally lived with her uncle, the long bike ride to work every morning became too much, and so she moved into lodgings in nearby Culford village, where she was much happier.

One of her first jobs was to cut away the grass from tombstones in the churchyard using a scythe, which she found very difficult. Other jobs included pulling mangolds (a root vegetable) to feed the cattle, hoeing sugar beet, caring for horses, cows, and sheep, planting trees and drilling fields, all without much experience or training.

'I liked working with those great big animals – the horses – they put up with lots of mistakes from us’.

There were six horses which Vivian and the other two land girls often cared for. When their main carer, Reg, was away, Vivian was the ‘horse girl’, which meant bringing the horses in every morning at 5.30am, grooming them and then saddling them up for work. While this was tiring work, Vivian didn't mind as she thoroughly enjoyed working with the horses.

However, working with horses could often be unpredictable. In one instance, Vivian was asked to take a horse and tumbril filled with logs to a farm about a mile away. Because the road was wet, the horse slipped and fell down in the shafts. Just as Vivian was unloading the logs to allow the horse to get back up again, a tank came round the corner. As there was a training ground nearby, groups of 20 or 30 tanks would often go by which was a hazard, especially if one of the young horses was on the road who could be easily spooked.

She also experienced many injuries during her time as a Land Girl:

- In one instance, a cow, fed up with being milked, used their horns to put Vivian in the manger.

- She got a nasty bruise when one of the horses stood on her shoe while hoeing sugar beet

- She got a bad scratch when a tank went by and scared a cat which she was holding.

- Someone's fork went into her foot, twice, during harvest time where they would gather sheaves using forks on a horse drawn carriage.

All of these injuries resulted in numerous trips to the doctor!

Vivian on her 21st birthday. She said 'I'll always remember what I did on my 21st birthday. I was sorting rotten potatoes in the clamp!'

Vivian on her 21st birthday. She said 'I'll always remember what I did on my 21st birthday. I was sorting rotten potatoes in the clamp!'

Aside from all of her hard work during her time in the Women’s Land Army, Vivian had time to have some fun. She helped to organise dances in the village hall in Culford, which were attended by soldiers and airmen, and they helped to raise lots of money for charity.

Audrey Baxter

Audrey Baxter was part of the Women’s Land Army in Suffolk, and the following information is from an oral history interview with Audrey, by Vicky Abbott that took place in March 2020.

Audrey’s family, from Lowestoft, were heavily involved in the war effort. Her younger siblings, Gifford and Derek, were evacuated, her sister Joan married and moved to Oxford, another sister Margery joined the police force in Lowestoft, and her brother Ted joined the Army (all in one weekend!). This left eighteen-year-old Audrey and her sister Dorothy, who was already a Land Girl and living at home. Audrey decided to join the Women’s Land Army alongside her sister.

During their time as Land Girls, Audrey and Dorothy would often do two milk rounds per day at Oulton Broad and Pakefield in Lowestoft. They tended to be long days and the sisters would have no break until they returned at 3pm. Once back at the farm, Audrey would wash the bottles ready to be refilled for the next morning.

A photograph taken of Audrey Baxter in March 2020 during her interview with Vicky Abbott, wearing a Land Army hat

A photograph taken of Audrey Baxter in March 2020 during her interview with Vicky Abbott, wearing a Land Army hat

Audrey Baxter wearing in her uniform during her time as a Land Girl in Suffolk

Audrey Baxter wearing in her uniform during her time as a Land Girl in Suffolk

As well as doing the milk round, Audrey also worked on the land. While the sisters received no training, they had some experience helping their father keep his large garden. When asked about a typical day as a Land Girl, Audrey remembered going to work at 7.30am, and being given her task for the day by the foreman of the farm. Daily tasks would vary depending on the season but could involve hoeing, muck spreading, chopping kale or setting potatoes. Lunch was at 12pm, and her day usually finished by 5pm.

As Audrey lived at home during her time in the Land Army, she mentioned that her social life was not very exciting, and her weekends consisted of shopping and going to church with her sister. However, Audrey and Dorothy did have some fun with the other workers. Listen to this recording of Audrey describing a prank her sister played on one of the male workers:

Muriel Gibb

Muriel Gibb shared her story with the BBC's WW2 People's War project, which ran from 2003 to 2006. The aim of the project was to collect memories of people that lived during the war, which would form a digital archive for future generations to learn about World War Two. Over 47,000 stories have been collected and the site will be hosted on the project website for the foreseeable future, before being deposited at the British Library.

Muriel submitted her story through Suffolk Archives in Lowestoft, so a copy is also in our collections.

Muriel was not made particularly welcome when she arrived at her new workplace:

'The start of my time in the Land Army didn’t go too well, as on the way to my billet, a lady startled me with the words “You keep your hands off my Sam, I have heard what you lands army girls are like”'

The farm staff also took a bit of time to come round to working with a woman:

'Arriving at the farm, where I was to work in the dairy, I found the cowman hadn’t wanted a girl. He wouldn’t speak to me that day and this went on for a whole month. I found this very difficult as I was expected to feed the calves not knowing how old they were, but with the help of Alf, the horseman, I survived. Eventually the cowman, Ernie came round, especially after the farmer said he would be the first one to go if he didn’t.'

One of the things Muriel found difficult was being expected to eat the animals she had helped raise - at the harvest supper she couldn't face eating Horace the pig, and was 'teased for weeks' about not eating meat.

You can find Muriel's story on the BBC People's War website here.

Two Suffolk Sisters

Barbara and Vera Halls grew up in Great Barton, near Bury St Edmunds. Barbara, the older of the two, worked in a newsagent’s shop before she joined the Land Army. She had various jobs during her service but can be seen here working with two other Land Army girls at Watson’s Timber Yard at Bury St Edmunds.

Barbara Halls, bottom right, sporting a bandage on a finger injured at work. Photo courtesy of Peter Cutts.

Barbara Halls, bottom right, sporting a bandage on a finger injured at work. Photo courtesy of Peter Cutts.

Barbara’s sister Vera was about two years younger and also served in the WLA. In the picture above she is looking her best for the photograph wearing her uniform with the tie. According to Vera’s daughter, she was quite a strong character. She did not consider herself a ‘proper’ Land Army girl because she worked for a really nice old local farmer and was only prepared to do jobs that she enjoyed like driving the tractor. One day she had to milk the cows so she didn’t go into work the following day!

The farm produced sugar beet which was all loaded onto a trailer by hand ready to go to the factory. After delivering sugar beet one day, Vera got a puncture on the return journey. She continued to drive the tractor all the way back which wrecked the wheel and tyre.

On another occasion, when the tractor broke down, she drove it into a ditch and left it there!

Barbara Halls (left) working at Watson's Timber Yard in Bury St Edmunds. Photo courtesy of Peter Cutts.

Barbara Halls (left) working at Watson's Timber Yard in Bury St Edmunds. Photo courtesy of Peter Cutts.

Vera Halls in her Land Army uniform, including the optional tie. Photo courtesy of Peter Cutts.

Vera Halls in her Land Army uniform, including the optional tie. Photo courtesy of Peter Cutts.

The Women’s Land Army in the post-war years

Even after the Second World War ended the country still relied on its Land Girls to keep up food production. It would take a while for male agricultural workers to return, and the army of POWs farmers had relied on would disappear as men were repatriated.

The years towards the end of the war were, however, marked by bitter rows over the treatment of the WLA by the government. The Government planned to exclude Land Girls from all the post-war benefits which members of other services would receive. Members of the WRNS, ATS, WAAF, Civil Nursing Reserve, Police Auxiliaries and Civil Defence Services were all recognised in Government schemes – the WLA was not. Members of the other services had opportunities for post-war education and training, were allowed to keep more of their uniform, and received the war gratuity. The Land Girls even received fewer clothing coupons when leaving the service – 25030 – while members of the ATS received 160. While continuing to rely on their labour, the Government told the WLA they would get none of these.

The Chair of the WLA, Lady Denman, had spent years fighting for fairer treatment for the WLA, but resigned in February 1945 over this decision:

‘I have reached the decision to resign only because I have held the view that one of my chief functions has been to get a square deal for members of the LA and I have felt personal responsibility for policy affecting their welfare.’

Land Girls campaigned against the decision, some even going on strike, the national press took their side, and the issue was debated in parliament. In May 1945 the Government made some small concessions – the WLA would be eligible for the same training that was available to Civil Defence and Auxiliary War Workers, they donated £150,000 to the WLA Benevolent Fund, and departing members were allowed to keep their great coats (dyed blue) and shoes.

It was against this backdrop that the WLA took part in the Victory Parade on 8th June 1946. This was an opportunity for the public to show their support for the Land Girls, and their sympathy with their post-war plight. The July 1946 issue of the Land Girl reported:

‘The reception the Land Army got in the Victory Parade was almost overwhelming to the volunteers who took part in it. ‘It wasn’t even like a dream, it was like floating’, writes H. Taylor (East Suffolk), ‘the roaring came and went and for about half a mile I floated and my arms and legs went by themselves.’

The WLA was still actively recruiting in Suffolk in 1948, as part of a national recruitment drive:

‘the need for whose services is as great as ever. Girls are wanted for poultry, milking, market gardening, and field work of all kinds. Applications from farmers for the services of land girls much exceed the supply, and the immediate need is to raise the number of land girls in the county from about 325 to 500.’

As part of the recruitment drive a quiz was held in Bury St Edmunds:

‘Farming posers which would have shaken hardened farmers were capably answered by a former typist, machinist, cinema attendant, printing works hand, nurse, housemaid, and audit clerk, who formed the two teams competing in the Women’s Land Army Agricultural Quiz final at Bury St Edmunds on Wednesday night... Mr Shropshire, one of the judges, remarked ‘It is amazing how these girls have answered these questions. They must have studied extremely well, and very efficiently applied their powers of observation in the field, the market garden and the dairy… I wonder sometimes if these Land Girls have had the credit they deserve for their invaluable work.’

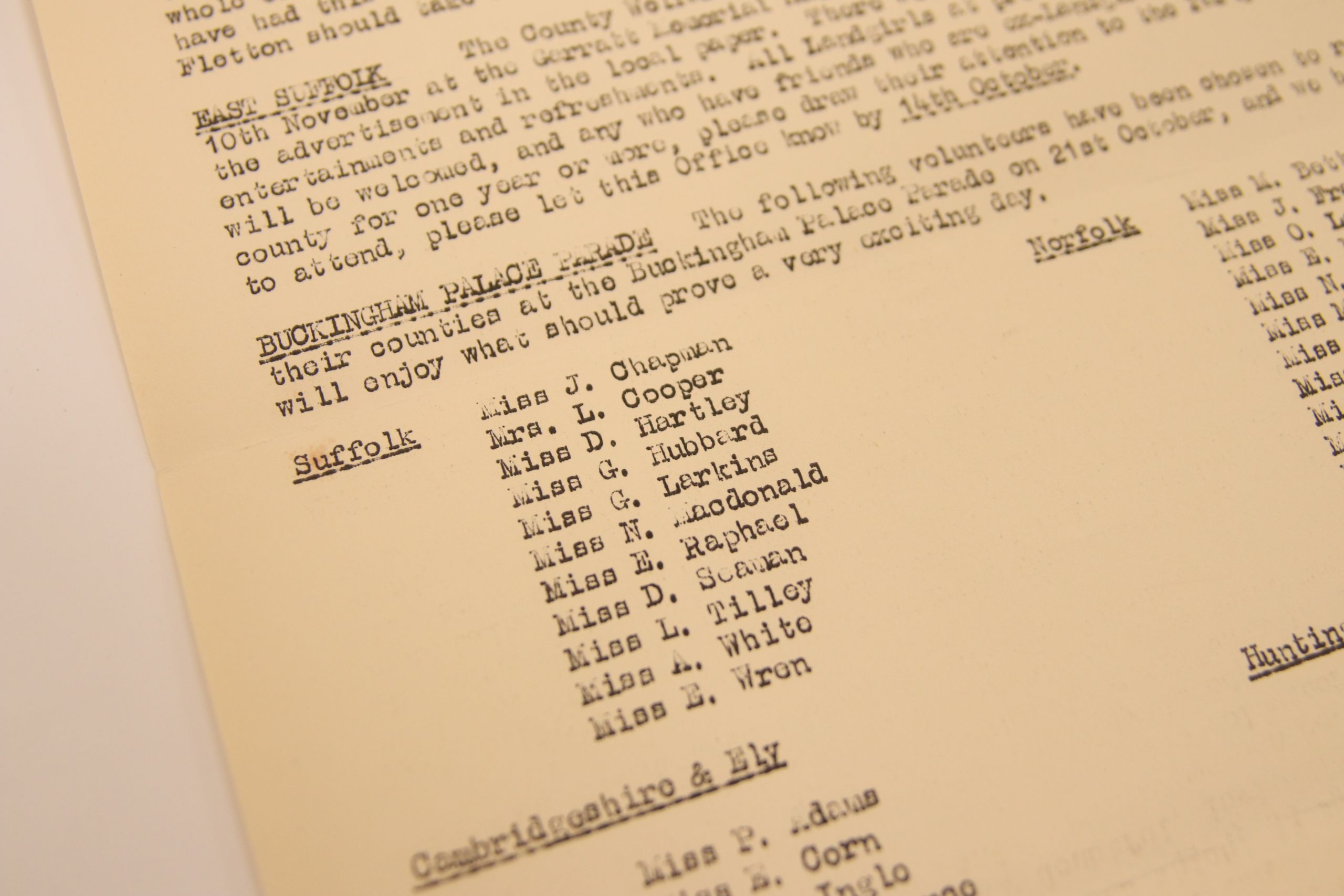

The WLA was officially disbanded in November 1950. There was a farewell parade on 21st October 1950, with 500 serving Land Girls marching past Buckingham Palace. The women who attended to represent Suffolk are named in the final Eastern Counties Newsheet for the organisation.

The final Eastern Counties Newsheet for the WLA, October 1950 (private collection)

The final Eastern Counties Newsheet for the WLA, October 1950 (private collection)

This silent footage from British Pathe shows the 500-strong contingent of the WLA being received at Buckingham Palace:

Nearly 250,000 women had served over 11 years. For many, the experience had been life-changing.

Once a Land Girl, Always a Land Girl!

Members of the WLA and the WTC had made lasting friendships during their service and held many reunions over the years. The Land Army National Reunion Association was founded in 1964 and published its first magazine in 1969. The group helped organise both regional and national get-togethers.

Waiting to be Appreciated

As the war ended a lot of women who had served in the WLA felt that their role had been under-valued and that they did not get proper recognition for their hard and sometimes difficult work. Those who had served in the armed forces received rewards and privileges that land girls missed out on.

After a long campaign, the government announced in 2007 that a special Veteran’s Badge could be awarded to surviving former Land Girls - over sixty years after the war ended! A memorial to both the Women’s Land Army and the Women’s Timber Corps was unveiled at the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire in 2014.

Land Army reunion at the Half Moon pub in Lakenheath (courtesy of Lakenheath Heritage Group)

Land Army reunion at the Half Moon pub in Lakenheath (courtesy of Lakenheath Heritage Group)

The Women's Land Army and Women's Timber Corps memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum © Colin Sweett (WMR-74909)

The Women's Land Army and Women's Timber Corps memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum © Colin Sweett (WMR-74909)

Find out more

Books and articles:

Tyrer, N. (2007) They Fought in the Fields: The Women's Land Army

Foat, J. (2019) Lumberjills: Britain's Forgotten Army

Burrows, L. (2004) The Women's Land Army in East Anglia, 1939-1950, Suffolk Review

Online:

Explore the Soil Sisters interactive map on Historypin - also created by volunteers from this project

https://www.womenslandarmy.co.uk/ - a website by Cherish Watton, packed with first hand testimony, photos, journals, letters – and much more.

https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/what-was-the-womens-land-army - 10 surprising facts about the Women's Land Army from the Imperial War Museum

Podcast from the BBC World Service about the Women's Land Army:

http://eafa.org.uk/work/?id=890193 - video from the East Anglian Film Archive of a WLA reunion in Ipswich in 1974