Sudbury's markets: past, present and future

For centuries Sudbury market has been the focal point for social and commercial activity, centred at the heart of the town. Explore the extraordinarily long history of the market, who was involved with it, and how it has changed from Saxon times to the present day.

Early days: a mint and a market

Over 1000 years ago King Ethelred II founded a mint in his town of Sudbury. A Great Ditch was dug to fortify the most defensible part of the town providing security for the mint and the moneyers charged with production of the new coinage. Merchants also passed through, bringing with them currency and gold from their continental travels. A market would develop to provide for both temporary and permanent residents.

The Domesday Book of 1086 records both the mint and a market in Sudbury. By then it had acquired the status of a royal borough. Saxon kings created boroughs to free merchants, traders and craftsmen from the restrictions of the feudal system, primarily to boost the royal income.

Burgesses (freemen of the borough) were granted their own plots of land in exchange for an annual payment, many of them free of any agricultural service to the lord, with the intention of fostering successful trade. The Domesday Book shows Sudbury had 142 heads of household or burgesses living both within and without the Great Ditch, indicating a population of approximately 600 or 700.

Two officials, William the Chamberlain and Otto the Goldsmith, 'keep Sudbury for the King' (William the Conqueror). William the Chamberlain was probably the town- or port-reeve, a royal official whose duties included the supervision of trade, the collection of tolls, and witnessing of purchases: every transaction had its price. The port-reeve also had supervision of the mint and oversaw foreign exchange. The latest coins from Sudbury's mint are dated to 1139.

The cloth trade and continental connections

A small Jewish community was already established in Sudbury by this time, making their living by money-lending. Mercantile trade depended on credit and was intrinsically linked with the wool and cloth trade from earliest times. Sudbury was then one of only three East Anglian towns recorded as producing cloth. The English made light, cheap cloth which sold well in the Mediterranean world.

In 1202 the men of Sudbury paid 20s as a licence to the King's Exchequer 'to be able to buy and sell coloured cloth .... as they had done since the time of Henry II' (1154-1219). Sudbury merchants exporting cloth (usually through Ipswich port) brought back luxury goods such as wine, silver and spices as well as essentials such as woad and alum used in dyeing and tanning processes.

Between 1275 and 1282 the St Quintins, merchants from Amiens in France, were among several merchants recorded locally. Robert St Quintin of Sudbury sent cloths and wool to his brother John in Ipswich and he in turn was taxed on the importation of French fabric, wines and silver cups.

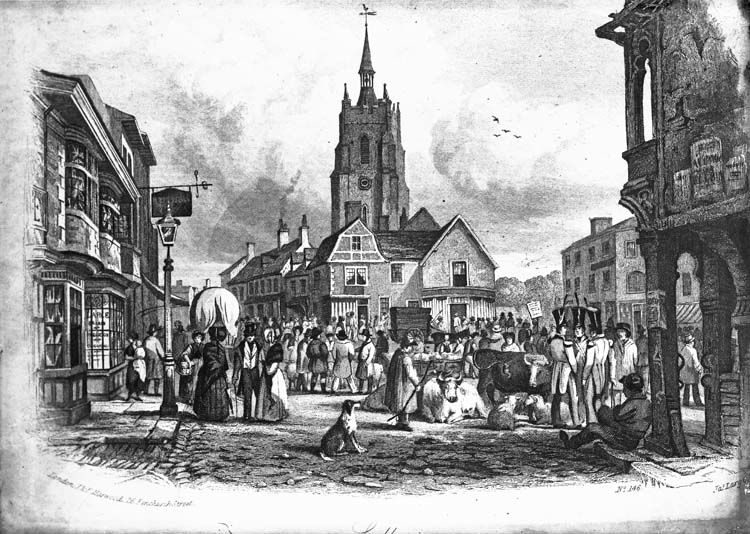

The stability of Henry II's reign, beginning in 1154, meant the Great Ditch was no longer needed and excavations have shown that sections of it were then filled in. The town's gates became established at the new bridge connecting with Ballingdon, at Borehamgate (Burumgate), and a Northgate at the top of today's North Street. The street market and commercial centre of the town developed on the hilltop around the crossroads where St Peter's church now stands.

From plague to prosperity

The arrival of the Black Death in Sudbury in 1349 had a drastic effect on the market. The 107 stalls recorded in 1340 had dwindled to 59 by 1353 - but as happened elsewhere, trade bounced back surprisingly fast.

Quickest to recover in Sudbury seem to have been the weavers: there were 31 in 1353, only one less than before the pestilence. Merchants, traders and craftsmen may have been as vulnerable as everyone else to the plague itself but were less affected economically than the agricultural majority by their burgess status.

Longer term effects of the plague actually helped the market in a positive way. A reduced agricultural workforce meant that the surviving population was able to command higher wages; in turn this brought them a higher standard of living with a better diet, better clothes and better houses.

The market adapted to meet the demand. The earlier luxury trade was soon also providing for ordinary people with good value cloths in bright colours. Local wills mention clothes of ruby, violet, green-coloured, blue and sanguine (blood red).

The lord of the manor in 1425, Edmund Mortimer 5th Earl of March, counted among his possessions the profits of 64 market stalls and 2 annual fairs in Sudbury. The burgesses paid him £10 a year for the right to collect the tolls and altogether the town brought him £24 a year, roughly equivalent to £15,000-£20,000 a year today - and Sudbury was only one of the hundreds of his manors and towns.

The fifteenth was a century of re-building, both of market confidence and of property funded by the great profits of the cloth trade. All three of Sudbury's churches were either completed or much enlarged between 1425 and 1460. Cloth trade magnates built substantial houses many of which have survived.

In the market, the new buildings that lined the north and south side included cellars, workshops, warehouses and great woolhalls. It is likely that around St Peter's church as it grew artisans' workshops and temporary housing began to cluster, adding to the 'permanent' stalls mentioned in early records. These probably formed the foundations of the properties that would, by the 17th century, nearly encircle the church. By the end of this period the market had expanded to fill all the available space around St Peter's church.

Illustration of a cemetery, from ‘Omne Bonum’ by James le Palmer, c.1360-1375, The British Library

Illustration of a cemetery, from ‘Omne Bonum’ by James le Palmer, c.1360-1375, The British Library

Illustration of harrowing a field with a horse, from The Luttrell Psalter, c.1325-1340, The British Library

Illustration of harrowing a field with a horse, from The Luttrell Psalter, c.1325-1340, The British Library

Illustration of merchant with scales, from Moral treatises, poems, prayers and hymns, c.1400-1450, Royal 19 C XI f. 31v, British Library

Illustration of merchant with scales, from Moral treatises, poems, prayers and hymns, c.1400-1450, Royal 19 C XI f. 31v, British Library

Trading in Tudor times

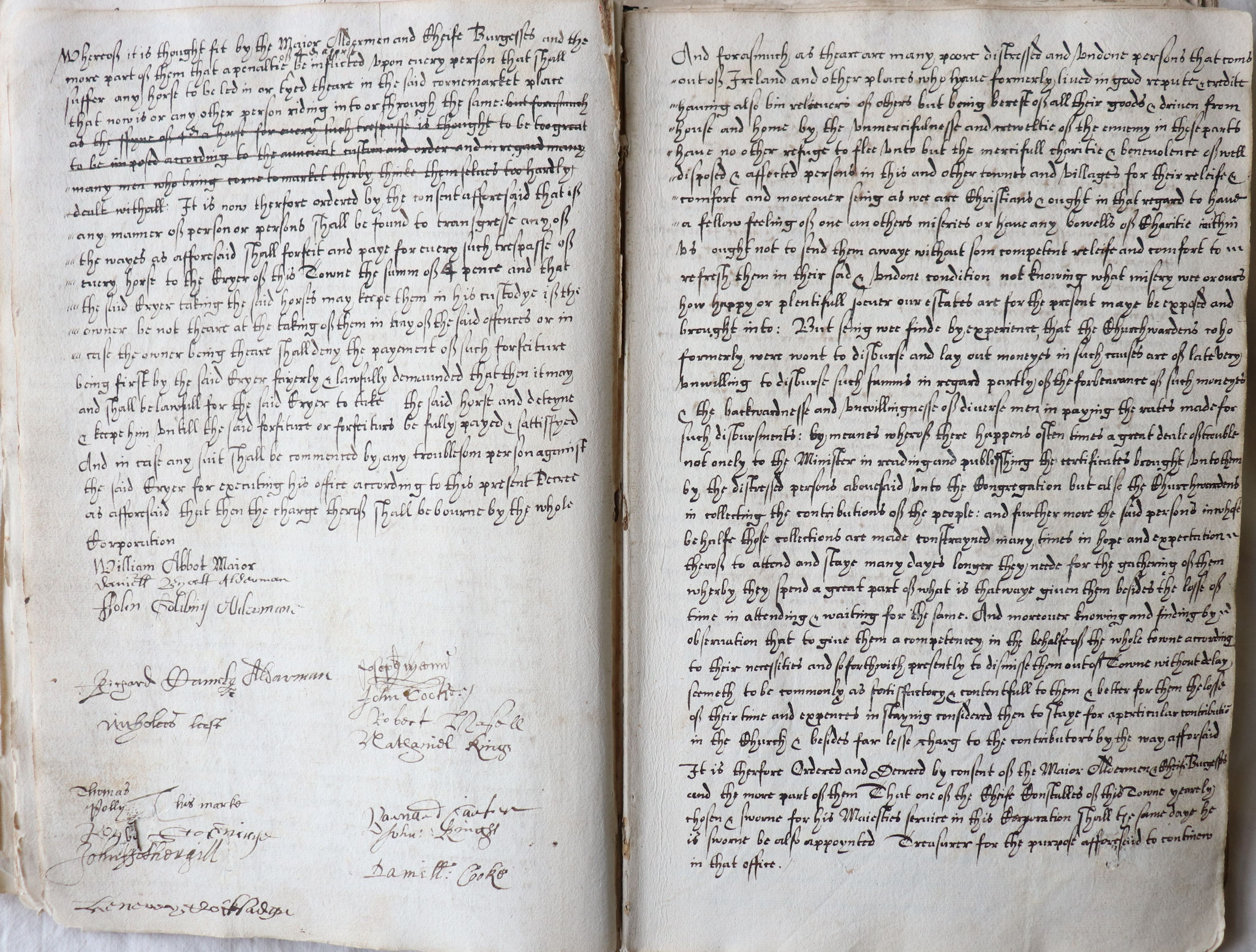

There is considerable evidence of the struggles of successive Mayors and other officials to maintain control of the constantly evolving market. By the early 1500s they were taking matters into their own hands as their authority came under pressure from an increasingly vocal population of clothiers and market traders. Tight Royal control in the town's early years had meant no specific market charter had been necessary but the lack of one was now causing real difficulty.

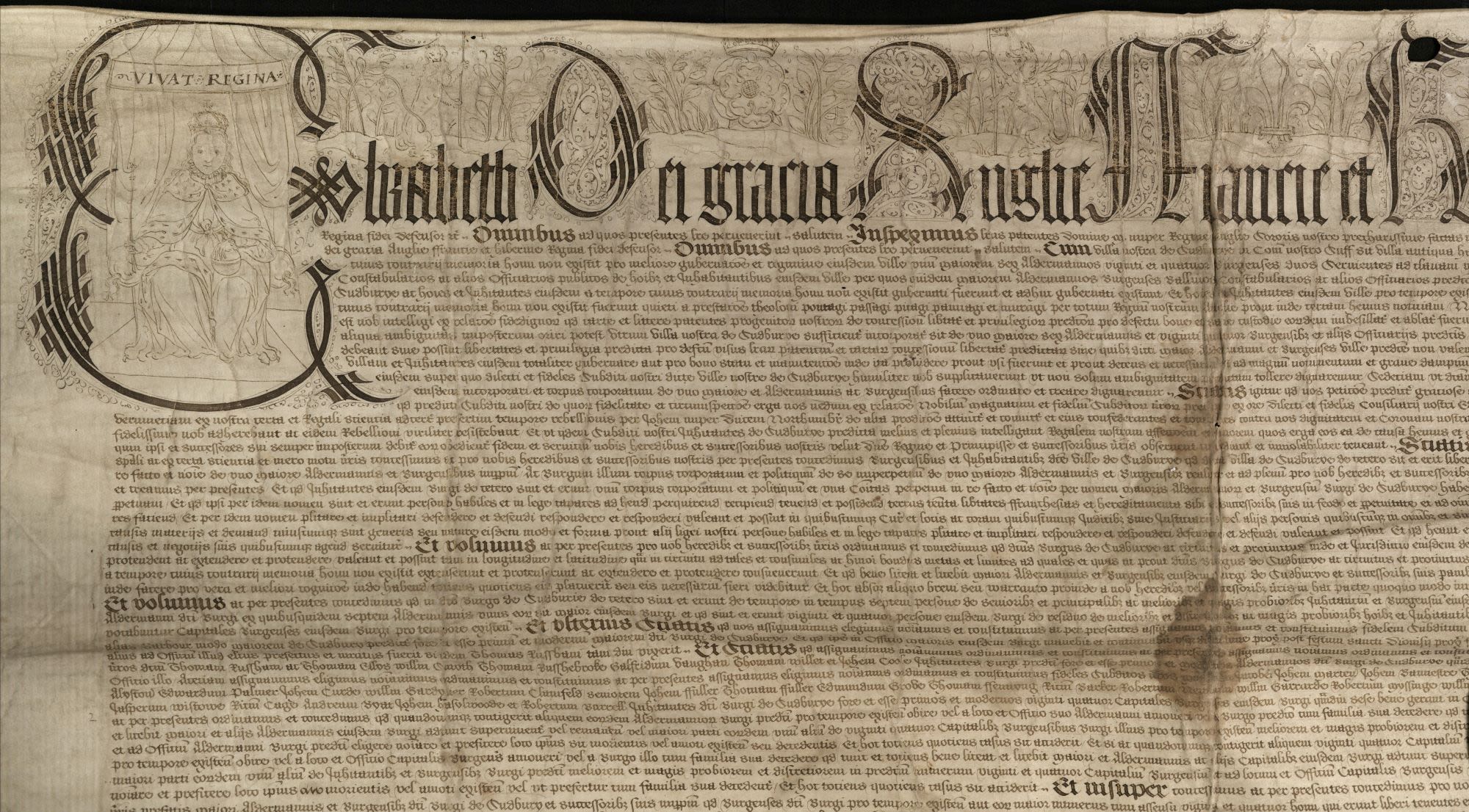

At last, on 30th May in 1554, in part in return for their 'conspicuous loyalty' to her in her struggle to claim the throne, the new Queen Mary granted the borough of Sudbury a Royal Charter. Among many liberties and privileges it granted the right to hold a market on Saturdays, 3 fairs yearly, and the right to hold a Piepowder court (court with special powers over the market) for the fairs.

The Mayor and his new Corporation would still pay a fixed amount for collecting the market tolls and rents for their lord but this newly established legal status allowed them to increase fines and control their own budget (subject to audit). For the rest of the century the Court Books show a marked increase in civic pride.

Using historic records we can reconstruct a remarkably detailed picture of the market in the 1500s-1600s. Let's take a look around...

Market stalls

Purple outlines indicate the locations of stalls recorded in surviving historic documents. Some were built onto existing houses and had upper rooms, even cellars. Others were in semi-permanent blocks of three or four. Provision was made by the borough for the storage of trestles brought out on market days or for the annual fairs. At least 30 butchers' stalls alone are recorded between 1550 and 1650, some on long leases, some let weekly or annually by the borough.

Light industry

Sudbury's market area wasn't only for retail but also manufacturing and light industry so the detritus of a normal day's business would have been considerable. A cluster of buildings grew up around St Peter’s church which included a brasier's furnace, slaughterhouses, a tallow chandlery, wool processing yards, and all with the constant passage of assorted livestock.

Buildings around St Peter's - Sudbury Photo Archives - catalogue ref: pa1135

Buildings around St Peter's - Sudbury Photo Archives - catalogue ref: pa1135

The Bay Hall

No. 10 shows the location of the Bay Hall, another of the buildings surrounding the church which has been demolished. It seems to have started life as a single-storey building for the stalls of shoemakers. When Suffolk's weaving industry was threatened by imported cloth in the 1560s, Sudbury was one of the few towns open to change and embraced new technology to produce the new types of cloth everyone then wanted (known as bays and says). The building was given an upper floor, the 'bay hall' where the fabrics could be stored, inspected and sold to visiting merchants.

Butter Cross

No. 6 on the map indicates the location of the Butter Cross, which is thought to be a circular or hexagonal structure with a roof. It stood in the area known as the Poultry Hill Market where not only poultry and dairy products were sold but also fish and other edible stuffs.

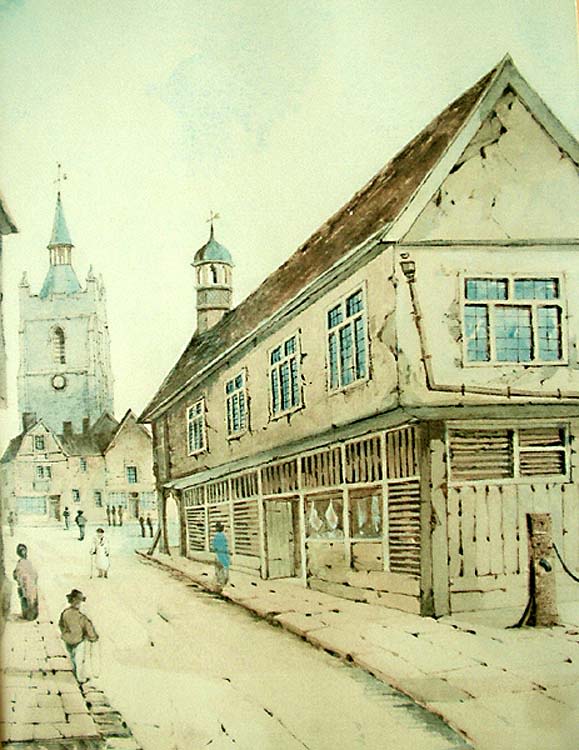

The Moot Hall

This was the administrative centre for the Borough of Sudbury. Bread was weighed and evaluated here before the 8.00am bell (on the roof) was rung to open the market. Weights and measures and scales were kept here to ensure fair trading, and squeezed into the building were a couple of butchers stalls and the town gaol.

Moot Hall 1825 - Sudbury Photo Archives - catalogue ref: pa759

Moot Hall 1825 - Sudbury Photo Archives - catalogue ref: pa759

Outside the Moot Hall were the stocks and pillory. Those convicted of minor offences would be locked in these for market goers to hurl insults and rotten food at. There was also a whipping post, often used in cases of immorality. It was also a punishment for theft as in the case of George Colman, a tailor, found guilty of stealing shoes worth 8d from the stall of Ozias Adams. He was ordered to be harshly beaten (‘graviter flagellat’).

The Moot Hall was pulled down in 1845. The building materials were sold and the money put towards the building of a new Town Hall with a purpose-built prison behind.

The Cage

Back at the north-east end of the market was The Cage. This was for summary justice, a single bay, tile-roofed structure probably with barred windows, for temporary punishment, visible to all market-goers.

Sudbury behaving badly

Complaints about bad behaviour were a regular feature in the Borough Court Books. At one point in 1647 it all became too much and there's a passionate entry showing that it was not only the livestock causing problems:

'Many brutish people next beside the church walls and paths leading to the church of St Peter's, inhumanely, more like beasts than men, defiling the same .... whereby all passengers both town and country people going to hear the Word preached have their senses much annoyed by the noisome scents and savors .... like persons commonly pissing against the walls .... (so that) people resorting for buying and selling of corn, yarn and other things take note thereof ... to the infamy and discredit of the Corporation .... anyone doing so and not removing their excrement to a suitable place to be fined or imprisoned at the Mayor's instruction'.

Demolition and rebuilding

Some of the market's oldest buildings, including the Butter Cross, the Cage, and the Bay Hall were demolished in the 1700s. This is likely to have been prompted by the building of a Toll Road through Sudbury. The route went along today's Gainsborough Street and the Market Hill where carriages, carts and horseback riders then had to squeeze between the muddle of stalls and houses to the north of St Peter's church before making a left turn up North Street.

Even more sweeping changes were to come. By the early 1800s there was an understanding that Sudbury's ancient, organically grown, infrastructure was just not designed for the traffic on which so much of the town's economy relied. There was also a growing awareness that the jumble of ancient properties, industrial premises and street trading with no mains water supply was a breeding ground for disease. An Act of Parliament passed in 1825 granted powers for wholesale changes to be made. 500 ratepayers petitioned vigorously against this Act but to no avail.

Over the next 20 years the market houses around St Peter's were demolished. By 1841 only Samuel Simkins' barbershop with in-house brasiers' forge and the adjoining butchers' shop belonging to Samuel Collis remained. They must have stood forlorn, as on a demolition site, just outside the windows of today's Prado Lounge.

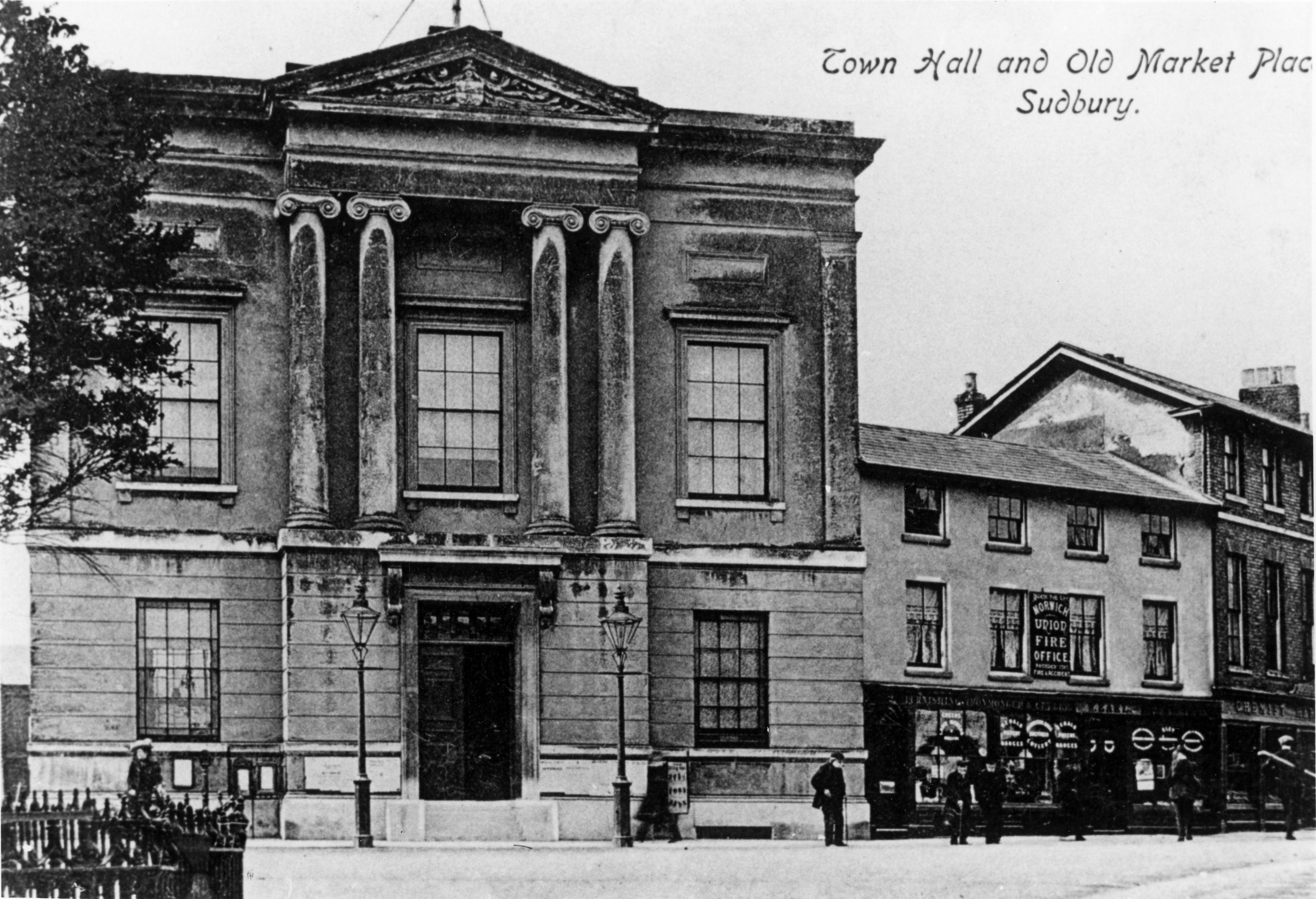

As for the Mayor and Corporation, their immediate priority seems to have been to give themselves a new Town Hall. The Moot Hall certainly was ancient, not to mention an obstacle to traffic. They voted for the £750 needed to buy the even more ancient Chequers Inn from one of their number. It was soon demolished, the materials sold off, and an elegant new Town Hall constructed between 1828 and 1830.

By 1840 attention was become focussed on the other end of the market where passionate argument raged about alternative sites for a new Corn Exchange. There was a strong lobby pressing for a Corn Exchange to be built where the remaining market houses still stood around St Peter's church.

Designs were drawn up to include a 35' (10m) carriageway between the church and proposed Exchange. This design was beaten out by another group on the council, who decided to purchase the old Coffee House as the site of the new Corn Exchange.

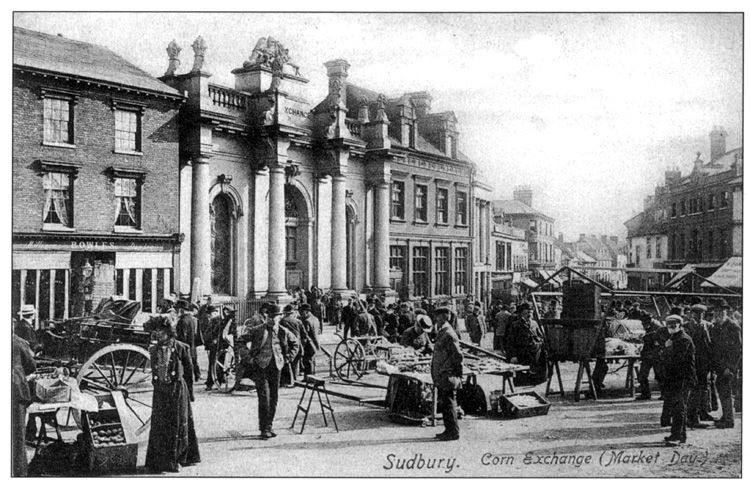

Excavations began on the foundations for the new building in August 1841 and by February 1842 it was near enough finished to be opened to the enthusiastic public.

That year the Town Council made an order that the old Moot Hall was, at last, to be demolished but it had acquired several 'barnacles' with age including a silversmith's home and workroom, and a drinking house called the Bushell, neither belonging to the one-time Corporation and it would be another three years before it finally went.

Photo of Sudbury Town Hall, Suffolk Archives, K681/1/440/46

Photo of Sudbury Town Hall, Suffolk Archives, K681/1/440/46

Print of Sudbury Corn Exchange, 1850, Sudbury Photo Archive, pa888

Print of Sudbury Corn Exchange, 1850, Sudbury Photo Archive, pa888

The Corn Exchange

The Corn Exchange was where local farmers would have sold their grain harvest. Farmers would bring in samples of their grain, perhaps in a small bag or paper envelope, to show to the grain merchants sat behind their tall wooden desks.

Photographs from the early 20th century show well-dressed farmers leaving the Corn Exchange to go to the market or perhaps to continue their business at one of the local pubs.

Street scene showing Sudbury Corn Exchange, Sudbury Photo Archive, pa265

Street scene showing Sudbury Corn Exchange, Sudbury Photo Archive, pa265

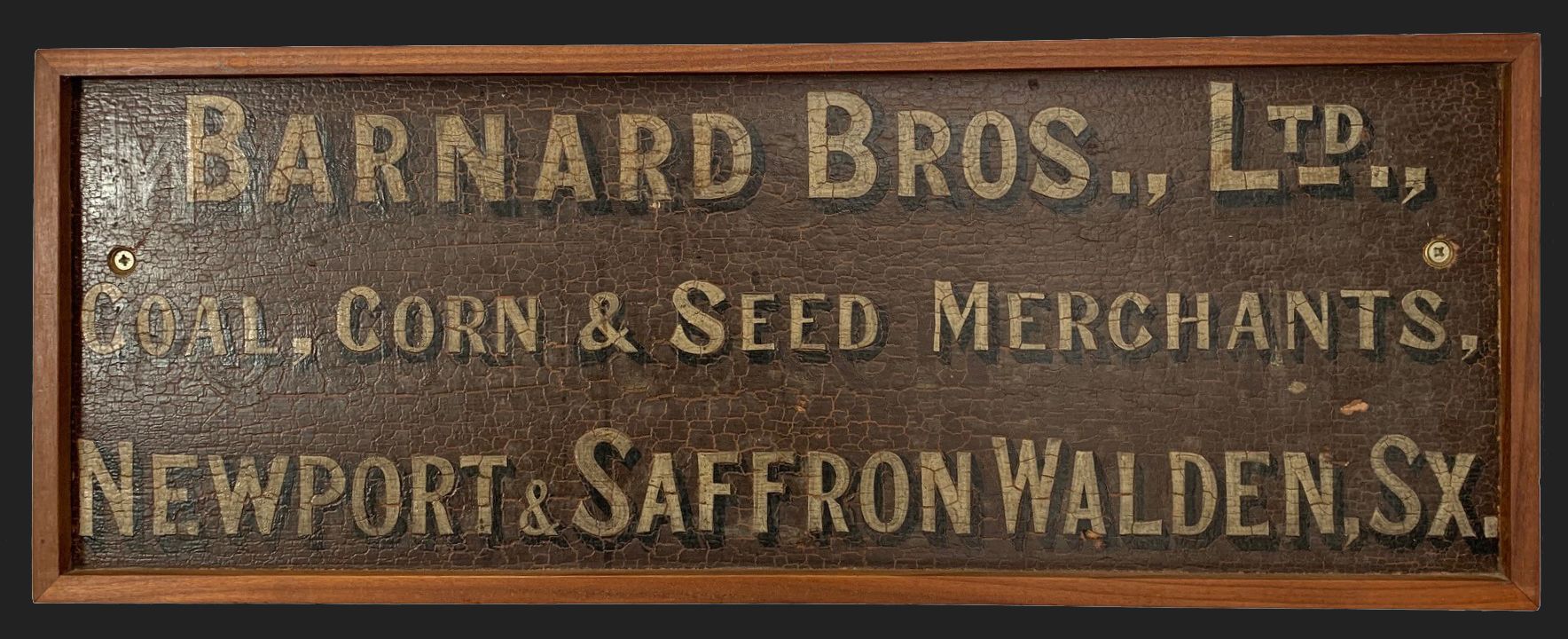

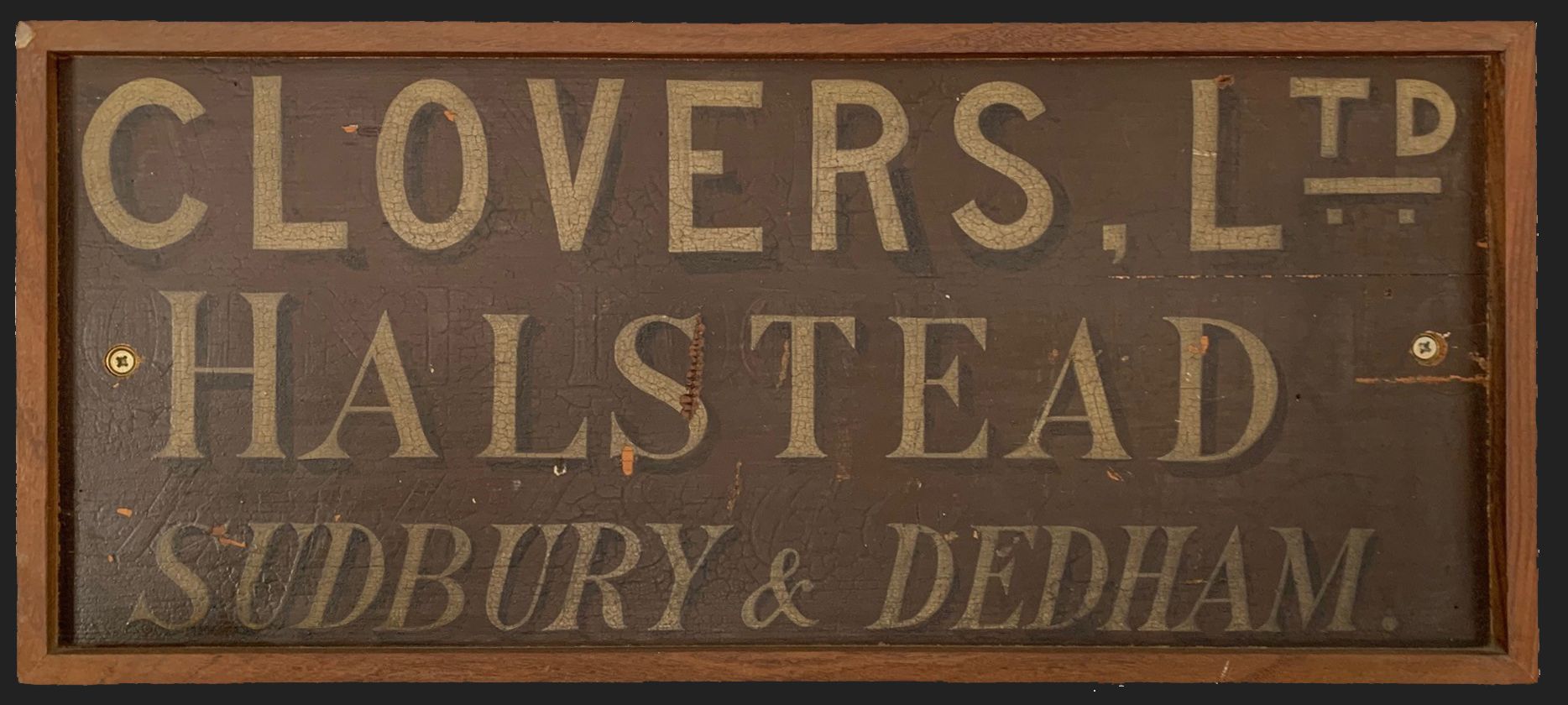

In the early 20th century there were still many local grain merchants and two local mills, one in Walnutree Lane and the other at Great Cornard.

Thursdays was also when the Corn Exchange (now Sudbury library) opened for trading. Millers, corn, merchants and feed merchants had their stands. Farmers brought samples of their crops in envelopes to show the merchants going from stand to stand to get the best price. After much haggling an agreement was mad with a handshake. Very much a man’s world, I don’t think there were any women there, only me!

As farming practices changed from the middle of the 20th century this type of farming became less economically viable. Smaller fields were replaced by larger ones, local mills closed and private corn merchants sitting in Corn Exhanges were replaced by bigger companies, who often buy the crop before it is even harvested.

By the 1950s the market operated so differently that the Corn Exchange was no longer needed for its original purpose. Fortunately, the building has now been restored and given a new use as the public library and used by the community as a source of technology, learning and leisure.

Interior of Sudbury Corn Exchange, Suffolk Archives, K681/1/440/30

Interior of Sudbury Corn Exchange, Suffolk Archives, K681/1/440/30

Wooden boards from the fronts of the sales desks of the Corn Exchange which can today be seen in Sudbury Library

Wooden boards from the fronts of the sales desks of the Corn Exchange which can today be seen in Sudbury Library

20th century characters

The 20th century dawned with Sudbury market still holding a central place in local society.

People could now travel into town from further afield, with more buses running on market days to bring in customers from the surrounding villages and farms. It was reckoned that it was from 10am when the town really started to bustle on a market day.

‘And then obviously I went round the market with my mother and the very thing I always remember her buying and was fish, bloaters, kippers, were a regular thing on a Saturday for Saturday teatime… my mother used to toss ‘em in flour and fry ‘em in the pan’

Some of the traders travelled from even further afield, such as Ben Clark who came up once a week from London to run his fruit and veg stall. Customers of Ben's may well remember his Cockney patter entertaining the shoppers of Sudbury on a Thursday. For Sudbury residents recently arrived in the town from London his voice was a welcome sound.

Ben Clark's greengrocers stall in the 1970s, photo from Sue Tibbetts

Ben Clark's greengrocers stall in the 1970s, photo from Sue Tibbetts

Ben Clark's fruit and veg stall was made up of two barrows wheeled out every week and stored behind The Christopher pub (Sudbury Photo Archive, pa343)

Ben Clark's fruit and veg stall was made up of two barrows wheeled out every week and stored behind The Christopher pub (Sudbury Photo Archive, pa343)

Throughout this project people have been contributing their memories of some of the stallholders who worked in Sudbury during the 20th century. Alongside the butchers, fishmongers, and greengrocers were some more unusual and eccentric businesses.

From the 1950s-1980s there was a stall known as Jim’s. Jim had a van that was parked at the extreme east end of the market close to the church. Easily identified, he wore a sheepskin coat that had seen better days and displayed the items he had to sell on the pavement. Some of the items would be dented tins of food without a label; buying these one took pot luck that the food inside was what he said, cats might end up with baked beans instead of cat food. Also amongst his stock might be toys in damaged boxes or various other items, he might sell in a Dutch auction style starting at the higher price and dropping in until he felt he had enough interest to get a sale. Children would go and spend pocket money on his stall, if they could not be satisfied shopping there then they had to look at spending more money and shop at Woolworths.

‘Another stall I do remember up the top used to be old Jim, he sold everything. Jim was Jim was a real character, he really was’

One stall in the 1970s was dedicated purely to the sale of bananas. The bananas were displayed in tiers on the stall and the riper ones were obviously cheaper than those that were still slightly green in colour.

There are also fond memories of Freddy Brown, a local man who was short and stocky in build always seen wearing buskins. While helping stallholders pack away and clear their patch, he would find good food that was on the floor but still perfectly fit to eat and give it to anyone he saw passing.

Lavinia Bruce with her daughter Irene, aged 4. Behind them is the linen stall Irene remembers: '‘The other wonderful stall I always remember at the bottom of the market hill opposite what used to be called the Black Boy is now called the Lady Elizabeth, was a wonderful linen stall. They had everything that you could think of in the household range … all on the top of these great big linen baskets with leather straps on the front’

Lavinia Bruce with her daughter Irene, aged 4. Behind them is the linen stall Irene remembers: '‘The other wonderful stall I always remember at the bottom of the market hill opposite what used to be called the Black Boy is now called the Lady Elizabeth, was a wonderful linen stall. They had everything that you could think of in the household range … all on the top of these great big linen baskets with leather straps on the front’

The Banana King stand in the 1970s, photo from Sue Tibbetts

The Banana King stand in the 1970s, photo from Sue Tibbetts

The Market Hill remained at the centre of social and civic life in Sudbury in the 20th century. With its prominent and central position it was the ideal location for parades and processions, celebrations such as Royal Jubilees, May Day fairs, and the lighting of the town for Christmas. It has been the site of dancing and celebrations such as the millennium and VE Day in 1945 when searchlights lit up the night skies around the tower of St Peter’s Church.

Bargain Hunt

In the days before eBay and car boot sales the dead stock market allowed people to sell second-hand household items, and was ideal for anyone looking for a bargain. In the early part of the 20th century this sale was held at the Drill Hall in Gainsborough Street. After the Second World War it moved to the undercover part of Oliver’s Cattle Market in Burkitts Lane.

As people modernised their houses in the mid-20th century, bringing in running water and appliances such as washing machines, one would frequently see the remnants of an earlier way of life at these sales. Unwanted aluminium baths, washing tubs and dollies and scrubbing boards would be found at the weekly auction together with the large mangle that used to be kept in the backyard to wring the water out of the unwieldy large bed sheets.

At the end of the Second World War when it was still difficult to obtain new cooking pots, household linen and hardware the auction was an invaluable source for the new housewife to make such purchases at an economic price.

Gradually as the local area became associated with the antique market the sale was useful for restorers of antique furniture to buy old furniture to restore and sell on or to use the wood to restore other pieces. In the 1960s and 1970s Sudbury and Long Melford had a large number of antique dealers and restorers and quite a lot of trade was being done with the antique markets of Europe via the ferries from Harwich. One lady remembered how her father a restorer of furniture would attend the auction whilst her and her mother went shopping, it was not uncommon for them to squash into the family car beside some large piece of furniture bought at the sale.

An auction in progress at the Corn Exchange. Photo by Humphrey Spender, 1934. Sudbury Photo Archive, pa338

An auction in progress at the Corn Exchange. Photo by Humphrey Spender, 1934. Sudbury Photo Archive, pa338

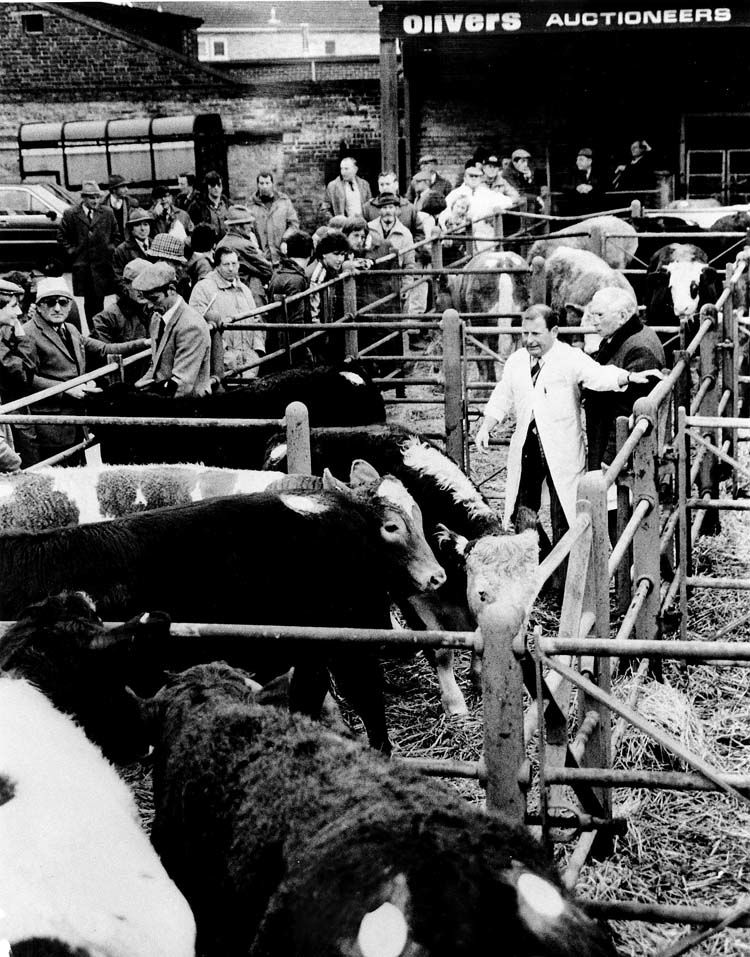

Sudbury Livestock Market

The buying and selling of livestock would always have been a feature at Sudbury market, but over time a dedicated livestock market formed. This began on Market Hill, but in the 1880s auctioneer George Cardinall opened a dedicated sale yard on Burkitt's Lane.

My parents (Brian and Dorothy Croker) had a small mixed farm at Great Henny. In the late 1940s, when I was 6 or 7 years old, sometimes my father took me to the Thursday cattle market in Sudbury to buy or sell cows. My first impression was the noise. Cattle bellowing, pigs squealing and the market workers, wearing brown warehouse coats and caps, shouting and banging sticks. As animals were driven into the pens and the metal gates clanged shut. Cows, some with their calves, bulls, bullocks, pigs and goats of all shapes sizes and breeds, for sale. Most of the livestock came to market in lorries or farm trailers. Some were even driven on foot through Sudbury down the Market Hill and up Birketts Lane to the cattle pens. All the traffic had to stop, until the animals were safely out of the way, no one seemed to mind.

Animals are, of course, unpredictable, and sometimes activity from the livestock market accidentally overspilled into the town. On one occasion, three cows came to the auction yard a bit late and when they had been unloaded they were not on their best behaviour. One of the animals took off and was eventually captured in a yard belonging to CAV in New Street. In the course of its escapade around the town it had broken several windows as a result of attacking its own reflection. Another chased a drover through the pens at the yard and would have attacked the man if it had not been for the fast reaction of a farmer saving him. The third was making roars like a lion and took an hour or more to be calmed down.

Auctioneers were also sometimes subject to unhelpful behaviour of their own animals. On another occasion the auctioneer had cattle in the cattle ring and felt a tap on his leg – this was a method used by some buyers to signal a bid was being made. The bid stood at £2, and after raising the price eventually to £5, the auctioneer looked down at his leg to discover the taps he recorded as bids were being made by his own dog.

The sale of horses began to decline in the mid 1930s when it becomes obvious that the employment of horses and horsemen was being superseded by mechanisation in the form of tractors. Cattle were still brought to the saleyard but the number was declining as mixed farming was changing to arable. By the 1980s the market was becoming a sale yard for pigs only and in 1986 the market closed. On the last day of the market there was one buyer at the sale and the auctioneer and him decided to hold a mock auction. Today the auction yard is a gymnasium.

View of Sudbury cattle market, likely from the 1970s. Sudbury Photo Archive, pa969

View of Sudbury cattle market, likely from the 1970s. Sudbury Photo Archive, pa969

‘I firmly remember the cattle market in Birketts Lane, a wonderful experience as a child … my mother used to make an effort to take me up there every Thursday. There’d be cows, beautiful Friesian cows, there’d be pigs, there’d be sheep. And as a child it was just absolutely wonderful to see those animals … There’d be the farmers there … and then they all used to meet and you’d see ‘em go in the Corn Exchange which is now Sudbury Library on the Thursday, from there they used to always frequent the Black Boy and that was their day, that was just the farmers’ day, and the day was for us as children’

Sudbury market today

As patterns of life have changed in recent decades, so did our patterns of shopping. Many aspects of modern life have been challenging for markets, as the daily shop has been replaced by the weekly shop. With more women working outside the home, the invention of fridges and freezers, the arrival of supermarkets, increasing car ownership, and commuting to work taking people away from their home towns during the day, many of us are not able to use markets in the way our ancestors did.

Nevertheless, after 1000 years of history Sudbury market is still going strong. It continues to be held every Thursday and Saturday, with additional Farmer’s Market on the last Friday of the month. It has meat from local farms, beer and wines produced locally as well as other commodities.

A new venture in the summer is to hold a “Green Sunday” market once a month, featuring eco-friendly ventures.

‘I'm certainly well-known on the market on Thursday, especially amongst the Cox family, they usually call my name from one end of the day quite big stall to the other and I usually say half of Sudbury knows that I've just arrived. I can only say they are such a wonderful hard working and family… and during lockdown last year they delivered weekly to us fruit and veg so I am eternally grateful to them’

Dave Munro, the fishmonger, starts his day on Wednesday at 12.30am when he starts to drive to Billingsgate market to buy his produce to sell on Thursday market.

Dan Ashdown who sells provisions and eggs, sources his eggs from Cornard and the provisions from wholesalers at Ipswich. He begins his day at 6am when he leaves home to collect his trailer and sets it in place on the Market Hill, then he returns to base to collect the trailer for Andy’s watch stall,

Cox the fruit and vegetable stall brings the lorries onto the market Hill to start setting up at 6am. The stall was originally one where the customer was served but in the last eight years it has become self-service with produce weighed on electronic tills, till receipt issued.

The Indian fast food stall The Curry Leaf, which operates on Thursday and Saturday markets as well as Braintree market on Wednesday sets up between 7.30and 8 am. Mr Wilson aims to use locally sourced food and gets his meat from the Market butcher John Colman. He began to set up business in Sudbury using a gazebo in 2015 but now has a permanent pitch on the market and a van in which he cooks his traditional food.

On Saturday market there are 2 fruit and vegetable stalls, Cox at the bottom of the Hill and Coles at the top. Coles have been trading on the Sudbury market longer than any other stall holder , their father began trading 59 years ago selling flowers and bulbs but when VAT was put on flowers he transferred to sell fruit and vegetables instead. They buy their produce from Spitalfields market and aim to have the stall set up and the lorries moved away by 9am. The Coles still sell their produce in the traditional way by serving from behind the stall. They also have stalls on Thaxted and Great Dunmow markets.

Green Sundays are a new opportunity for eco-friendly businesses in Sudbury.

Sudbury market on film

Journey through 1,000 years of history and hear what today's Sudbury residents have to say about the future of their market in this short film by the Offshoot Foundation, made with local young people.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to everyone who has contributed to this project, particularly Sue Tibbetts, Juliet Clarke, Angela McGarry, Eve Rice, Paul Press, and Sudbury Photo Archive.