Witches giving babies to the devil. Woodcut, 1720. ©Wellcome Collection.

Witches giving babies to the devil. Woodcut, 1720. ©Wellcome Collection.

Remembering Suffolk’s Forgotten Witches

Between 1645 and 1647 the Suffolk witch trials were some of the most brutal and widespread in England. Many of the stories of those accused of witchcraft have been lost to history, overshadowed by the notoriety of the witchfinders who condemned them.

Over sixty people were accused of witchcraft in Babergh and Mid Suffolk, with many being tried and executed. The Heart of Suffolk Witch Trials project is uncovering individuals' stories, exploring the witch trials, and the lasting legacy today.

Woodcut of Witches and the Devil flying on broomsticks, c.1720. ©Wellcome Collection.

Woodcut of Witches and the Devil flying on broomsticks, c.1720. ©Wellcome Collection.

Trigger Warning

Some topics and language featured in this exhibition could trigger an emotional reaction or cause offense. Archive content has been presented as it was originally created and may contain outdated cultural depictions or language. These were wrong in the past, and they are wrong today.

Topics: Misogyny, abusive language, child loss, death, discrimination, domestic abuse, mental health, misogyny, offensive language, outdated cultural depictions, persecution, trauma, violence, war.

What is a Witch?

The idea of the witch is thousands of years old and is first mentioned in Ancient Greek texts. The word and image of the witch has evolved through time, and each culture have their own stories and imagery of witches.

In the UK, witches are often portrayed as an ugly old woman with a large nose, moles and warts, standing over a cauldron casting malevolent spells. But it is important to remember that people accused of being witches were everyday people, women, men, young and old. Some may have used common folk charms, made healing remedies, helped with childbirth, or spoken spiritual phrases to help themselves or local people with day-to-day problems. But did this make them a witch?

Whether they practised healing, or magic, or not at all, those accused of witchcraft were used as a scapegoat for poverty, disease, death, crime, famine, plague, war, and local upheaval.

A witch holding a plant. Woodcut, ca. 1700-1720. ©Wellcome Collection.

A witch holding a plant. Woodcut, ca. 1700-1720. ©Wellcome Collection.

England in Turmoil

In Britain, belief in magic was for many people part of daily life. Villagers sought help and health care from cunning folk who were healers and charm-makers.

But witchcraft was feared by the Christian Church, seen as a pact with the devil. In 1486 German clergyman Heinrich Kramer published Malleus Maleficarum, or the Hammer of Witches. The book claimed that witches made a pact with the devil and would cast spells to harm others. Kramer believed that while anyone could be a witch, women were most susceptible to the powers of the devil. The book acted as a manual on how to detect a witch and use extreme torture to extract a confession. Kramer’s book fuelled suspicion and fear in communities across Europe.

In 1597 King James VI of Scotland wrote the book Daemonologie which claimed that witchcraft was real and must be eradicated. These beliefs lead to the 1604 Witchcraft Act which made practicing witchcraft a crime, punishable by death.

King James VI of Scotland overseeing the trial of women accused of being witches. 1591. ©Alamy

King James VI of Scotland overseeing the trial of women accused of being witches. 1591. ©Alamy

The Civil War

During the 1600s England was in turmoil. King Charles I believed he had the divine right to rule without the influence of others, even refusing to summon Parliament. But governing without Parliament made it difficult to raise money. Rising taxes and ongoing religious tensions angered many and led to Civil War in England in 1642.

People in East Anglia struggled with men away at war, famine, religious divisions, and economic hardship. Many Suffolk communities were Puritans and supported Parliament in the Civil War. They believed that witches were working against God and must be rooted out and stopped.

In times of hardship, people searched for scapegoats. Neighbours would turn on one another, accusing witches and the devil for the challenges they faced. Allegations and accusations of witches became rife, ripping through communities and leaving a legacy of persecution and loss.

John Speed Map of Suffolk, 1610. ©Suffolk Archives.

John Speed Map of Suffolk, 1610. ©Suffolk Archives.

The Witch Trials

The Witchfinder General

Communities looked for help to relieve their villages of the misfortunes they believed were brought onto them by witches.

Suffolk born Matthew Hopkins styled himself as the Witchfinder General, working with John Stearne. In 18 months from January 1645 to August 1647, they accused and condemned more witches than all previous English witch-hunters combined.

Hopkins claimed he was commissioned by Parliament, and with Stearne travelled across Suffolk in the summer of 1645. Stearne covered the west of the county and Hopkins the east, they brought at least 150 people to trial, leading to over 100 executions.

Print of Mathew Hopkins. K511.322. ©Suffolk Archives

Print of Mathew Hopkins. K511.322. ©Suffolk Archives

Who Did They Accuse?

Widows, especially those who were poor, old, or relied on the village for support.

Women who took up positions of authority or independence. Such as Midwives, healers, cunning folk, or even wealthy women.

Anyone against whom there was a dislike, or a neighbourly dispute.

Men and children were also accused but in smaller numbers than women.

Woodcut of a witch being executed. ©Alamy

Woodcut of a witch being executed. ©Alamy

How Did They Gather Evidence?

Collecting evidence was crucial for getting a conviction. The witchfinders enlisted local people to serve as watchers to gather proof and confessions. Watchers observed the accused, reporting back farfetched accounts of visits from familiars, believed to be imps taking the form of animals.

Once arrested searchers would strip the accused and examine their bodies for the devil’s mark. This could be physical signs like moles, or scars that supposedly indicated a pact with the Devil.

Those who bore a Devil’s mark would not feel pain or bleed. Witchfinders would use a tool called a witch prick, a hollow wooden handle that had a retractable point which would give the appearance of an accused witch's flesh being penetrated without blood, or pain.

To extract a confession those accused would be subjected to horrific torture. Including swimming tests, forced walking, sleep deprivation, and starvation. Many would confess just to make the torture come to an end.

Depiction of swimming torture for women accused of being a witch. From Witches apprehended, examined and executed, 1613. ©Wellcome Collection

Depiction of swimming torture for women accused of being a witch. From Witches apprehended, examined and executed, 1613. ©Wellcome Collection

Illustration of a witch prick, from the Discoverie of Witchcraft by Reginald Scott, 1584. ©British Library.

Illustration of a witch prick, from the Discoverie of Witchcraft by Reginald Scott, 1584. ©British Library.

A woman wearing a Scold’s Bridle over the head with a metal gag in the mouth. By Ralph Gardiner, 1655. ©British Library.

A woman wearing a Scold’s Bridle over the head with a metal gag in the mouth. By Ralph Gardiner, 1655. ©British Library.

Mid-Suffolk Accused

View of Rattlesden Village. K681/1/366/28. ©Suffolk Archives

View of Rattlesden Village. K681/1/366/28. ©Suffolk Archives

Rattlesden

Stearne visited Rattlesden in 1646, where a young boy was suspected of witchcraft. The boy confessed to having an imp and using it to harm others. Although he was initially released due to his age, he was later rearrested.

Following his mother’s execution for witchcraft, the boy claimed the Devil appeared to him as a horse. While imprisoned, a fellow inmate vanished. The boy said that the horse had carried the man over the prison wall to his wife’s house. A search confirmed the man was at home, just as described. The boy remained in prison through the summer of 1646, with no record of his fate.

Witches and Devils dancing in a circle, 1720. ©Wellcome Collection

Witches and Devils dancing in a circle, 1720. ©Wellcome Collection

Elizabeth Deeks, Rattlesden

Elizabeth Deeks’ mother was executed as a witch after she confessed that she had been instructed to renounce God and make a pact with the Devil.

Elizabeth was then accused of having been talked into making a deal with the Devil by her mother. Stearne’s account of his questioning with Elizabeth states that she maintained she had refused the devil repeatedly and was innocent. But later in the interrogation she confesses to having worked with imps.

Illustration of Stowmarket church. HD1678/128/1/1. ©Suffolk Archives

Illustration of Stowmarket church. HD1678/128/1/1. ©Suffolk Archives

Elizabeth Hubbard, Stowmarket

Hopkins and Stearne visited Stowmarket in Spring 1646. They were paid £23 for their work in the town, as well as accommodation and expenses.

Elizabeth Hubbard was a widow and was accused of entering a pact with the Devil and wishing harm upon her cousin. She was accused by a group of five men including John Stearne. After interrogation she confessed to having three imps who appeared to her as children. She was executed.

Drawing of Wingfield Castle. HD1678/151/1/1. ©Suffolk Archives.

Drawing of Wingfield Castle. HD1678/151/1/1. ©Suffolk Archives.

Elizabeth Greene, Wingfield

Elizabeth was a widow, who claimed to know that she was a witch because of marks found on her body. Asked how she acquired them, she said that accused witch Goody Wright of Stradbroke had sent three imps to her. Elizabeth was sent to trial.

Depiction of witches from The Wonderful Discoverie of the Witchcrafts, 1618. ©The British Library

Depiction of witches from The Wonderful Discoverie of the Witchcrafts, 1618. ©The British Library

Margaret Bennett and Mary Bush, Bacton

In Bacton, several women were accused of trading their souls to the devil to gain power over the village. A group of influential local men led the accusations. Mary was a penniless widow who was forced to beg door-to-door after her poor relief payments were stopped by the local Lord of the Manor, who was one of her accusers.

Elizabeth Watcham and Ellen Greenliefe were also accused in Bacton and interrogated by Stearne. All four women were arrested. Elizabeth was released, Mary and Margaret were sent to trial, and the Chelmsford Gaol book lists Ellen dying of bubonic plague whilst awaiting trial.

Wetherden Church. K681/1/492/1. ©Suffolk Archives.

Wetherden Church. K681/1/492/1. ©Suffolk Archives.

Elizabeth Fillet (Tillet), Wetherden

Elizabeth was accused by a local cobbler of causing his child to suffer from spasms and lice, and that his shop was plagued by rodents sent by a witch after his wife had refused to visit Elizabeth when she was ill.

Elizabeth was watched and searched by two local people who testified that she was a witch. Elizabeth was arrested, but there was not enough evidence to send her to trial.

A witch feeding her familiars. ©Alamy

A witch feeding her familiars. ©Alamy

Anne Hammer & Nicholas Hempstead, Creeting St Mary

Anne Hammer confessed to Stearne that she had been visited by two imps, which she sent to kill a child.

Nicholas Hempstead was tortured by Stearne until he confessed to sending his imps to kill an army horse, and attack men in his regiment.

Both Anne and Nicholas were named as witches, and Nicholas was executed.

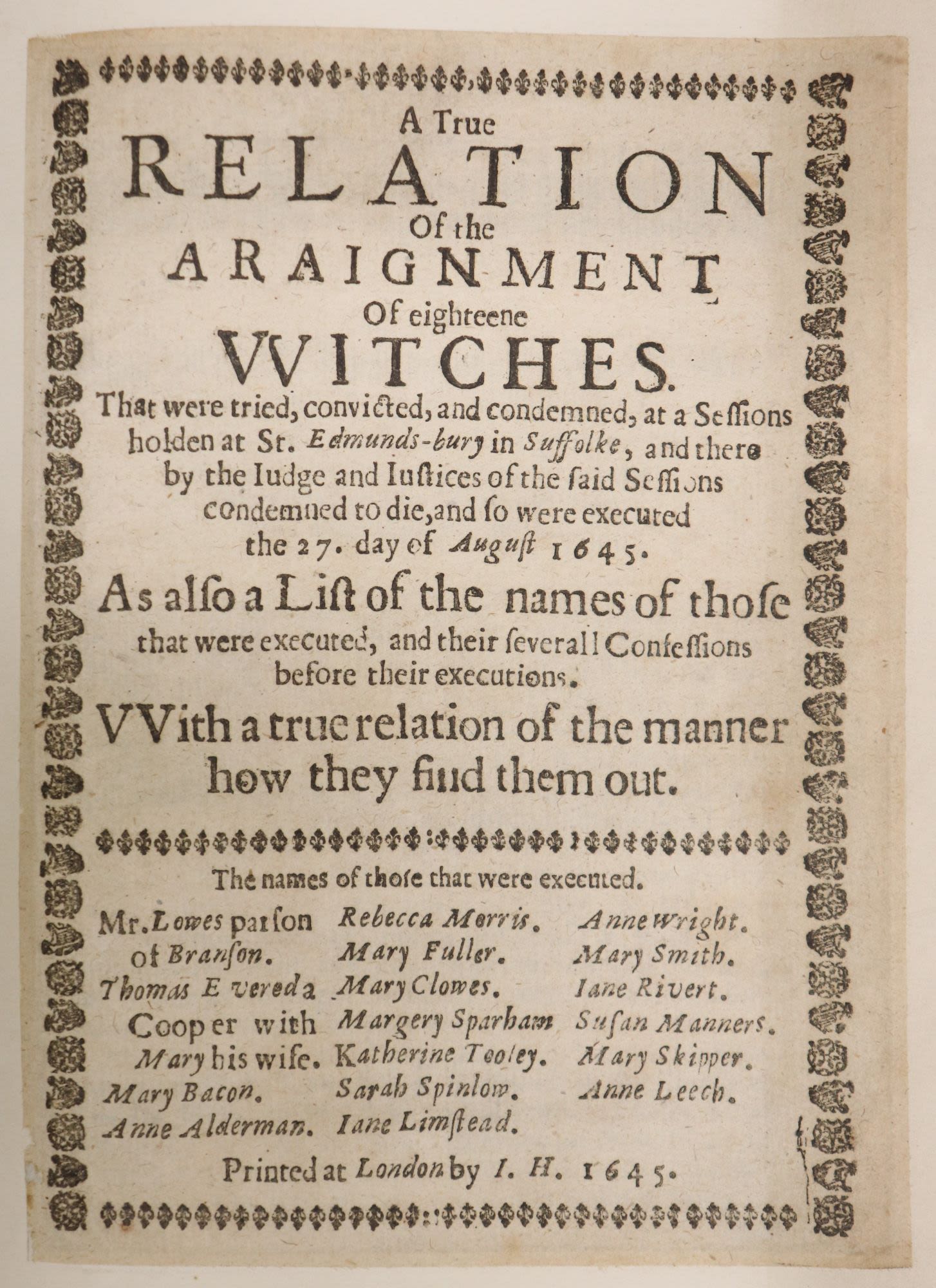

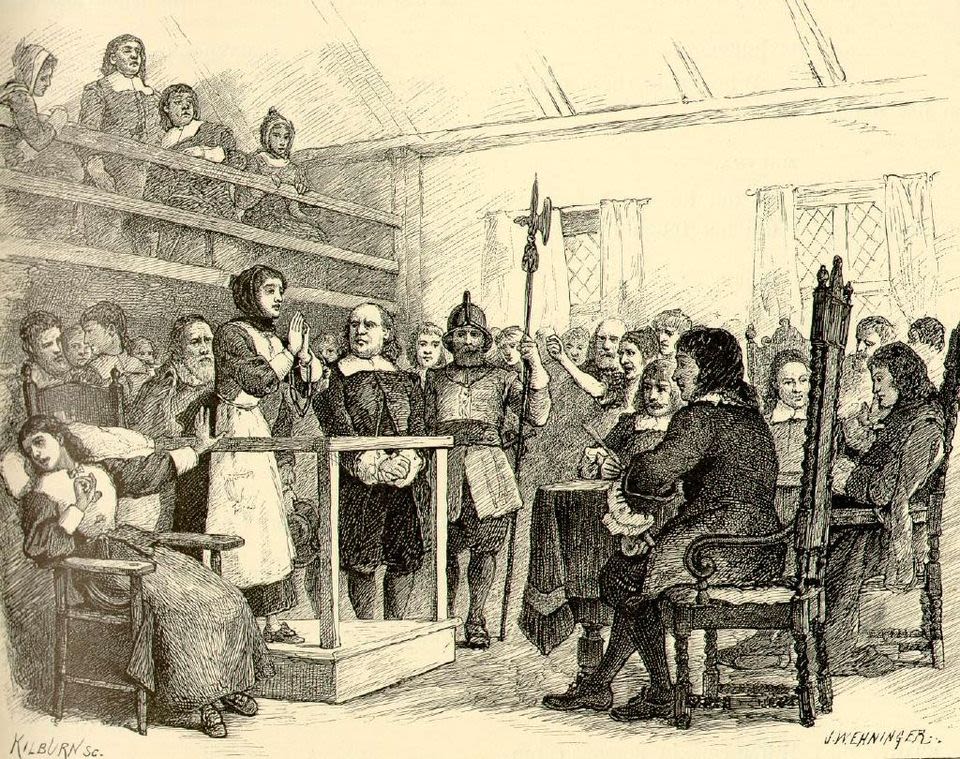

Bury St Edmunds Assizes, 26 August 1645

The largest witch trial in English history took place in Bury St Edmunds in August 1645. 140 accused people had been rounded up from across Suffolk and taken to trial.

On the first day the Grand Jury heard 90 cases, spending only a few minutes on each one. By the end of the day half of those brought to trial had been heard resulting in 16 women and 2 men being sentenced to death. They were hanged the following day.

The trial was interrupted by the advance of Royalist troops from the north, leaving dozens of people still awaiting trial. The official records from the next trial have not survived, but there are reports of mass executions of 60 or 70 people.

Pamphlet detailing the witch trials at Bury St Edmunds in 1645. HD1150/5. ©Suffolk Archives

Pamphlet detailing the witch trials at Bury St Edmunds in 1645. HD1150/5. ©Suffolk Archives

Babergh Accused

Long Melford Church. K681/1/308/2. ©Suffolk Archives

Long Melford Church. K681/1/308/2. ©Suffolk Archives

Alexander Sussums, Long Melford

John Stearne was born in Long Melford in 1610. During his work with the Witchfinder General he stayed in Long Melford. During this time Alexander Sussums, the first man to be accused of being a witch, handed himself in. Stearne searched him and found two witch marks. Alexander was sent for trial but acquitted.

Old Moot Hall, Sudbury. K681/1/440/18. ©Suffolk Archives

Old Moot Hall, Sudbury. K681/1/440/18. ©Suffolk Archives

Anne Boreham, Sudbury

According to Stearne, Anne was tempted by demons to forsake Christ and do the Devil’s work. A report states ‘Two Borams, Mother and Daughter’ were hanged at Bury St Edmunds, which is likely a record of Anne’s death.

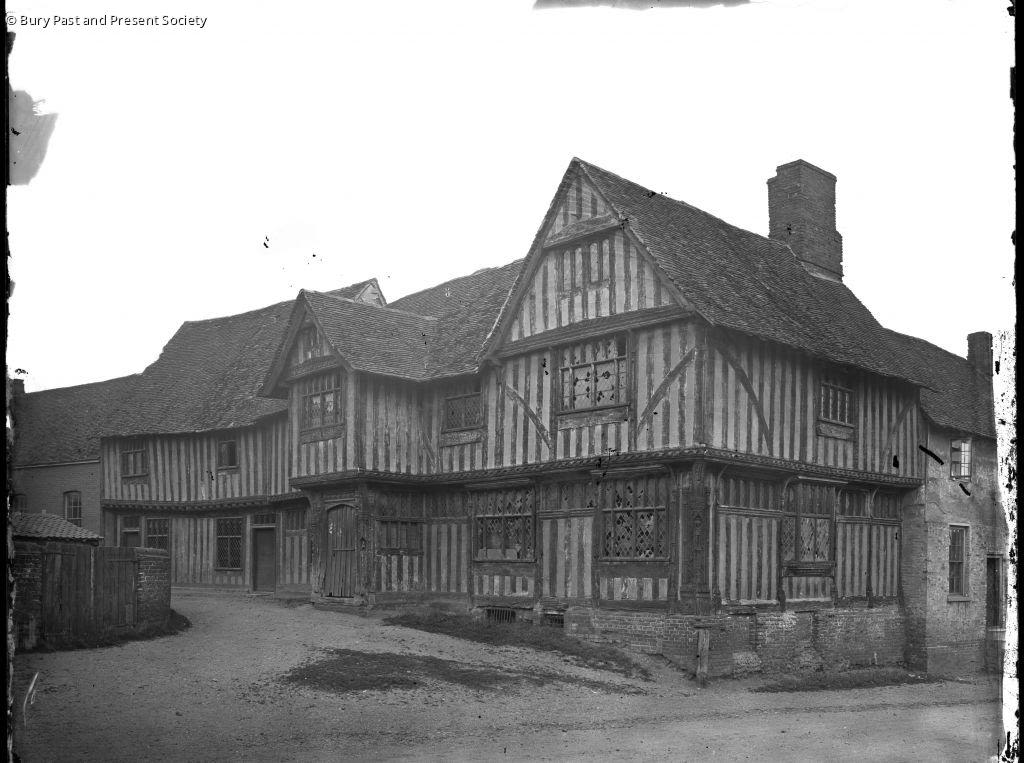

Photograph of Lavenham Guildhall. K505/2677. ©Bury Past and Present Society.

Photograph of Lavenham Guildhall. K505/2677. ©Bury Past and Present Society.

Anne Randall, Lavenham

Stearne arrived in Lavenham during a time when the local wool trade was in decline. The town was led by William Gurnell, a Puritan preacher known for his role in rooting out witchcraft.

Stearne heard the confession of Anne, who admitted to serving the Devil with the aid of two kitten imps. She confessed to raising a storm that killed William Baldwin’s horses after he refused her wood and sending her imp to kill Stephen Humphrey’s pig after he mocked her for begging. Anne was tried for being a witch and executed.

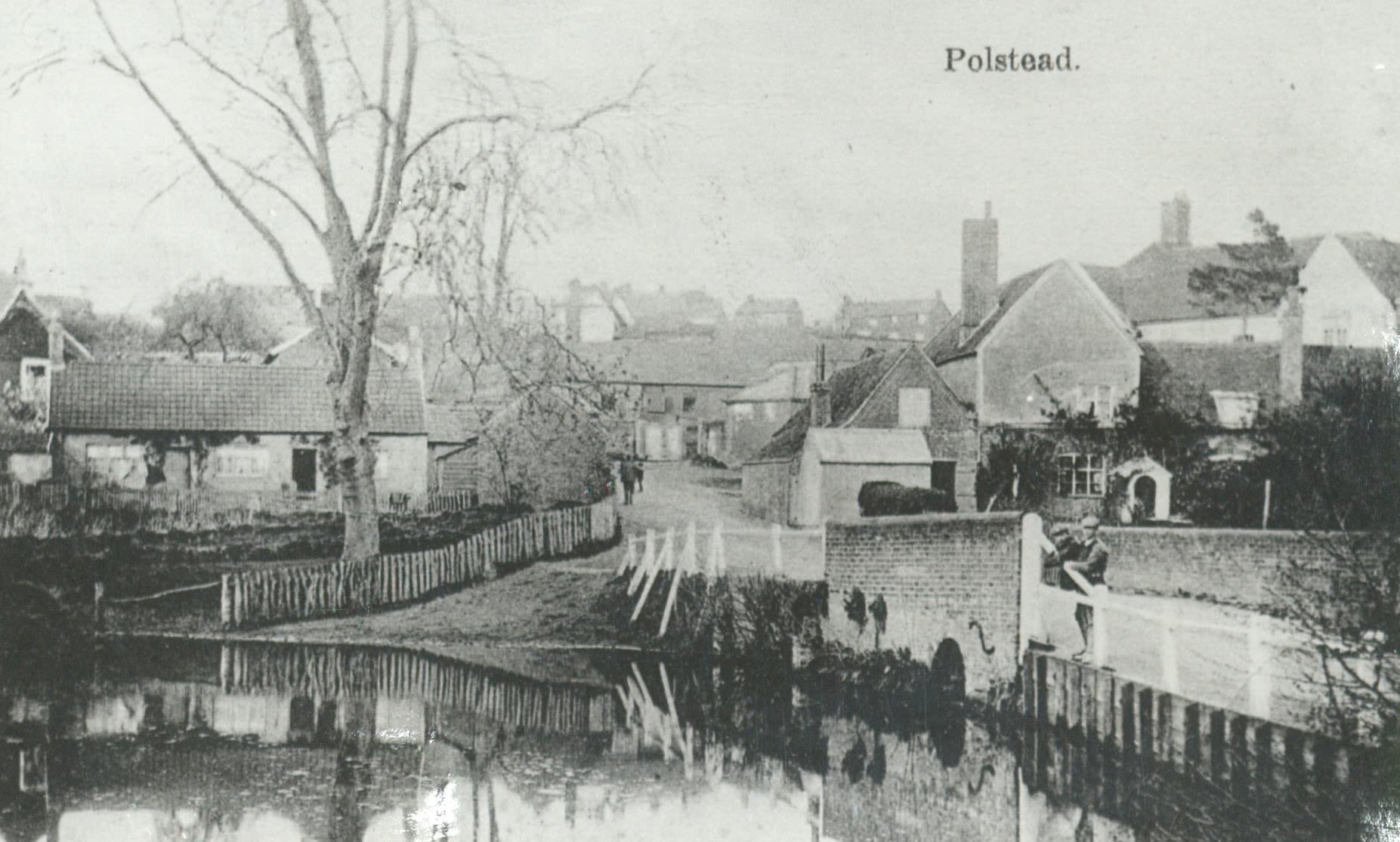

Polstead Ponds, c.1913. K681/1/366/16. ©Suffolk Archives

Polstead Ponds, c.1913. K681/1/366/16. ©Suffolk Archives

Joan Ruce, Polstead

Joan was a well-off widow who in 1640 fell under the suspicion of her neighbours after some of their livestock died. Under interrogation she confessed to having familiars in the form of three mice. She confessed to selling her soul to the Devil in exchange for money and imps, which she said she commanded to carry out killings. Joan was sent to trial.

Shelley Church. K681/1/394/4. ©Suffolk Archives

Shelley Church. K681/1/394/4. ©Suffolk Archives

Thomasine Ratcliffe, Shelley

Thomasine confessed that she slept with the Devil in the shape of her deceased husband, and that she had practised magic and charms. Thomasine was searched by the witch pricker Priscilla Briggs, who allegedly found two devil marks.

Two men claimed they had been infested with lice, and seen their livestock die after falling out with Thomasine. She was also blamed for the deaths of two children. Her interrogation doesn’t record whether Thomasine was sent to trial.

Church Farm Chattisham. K681/93/4. ©Suffolk Archives

Church Farm Chattisham. K681/93/4. ©Suffolk Archives

Mary and Nathaniel Bacon, Chattisham

Mary and her husband Nathaniel Bacon were both brought before a magistrate and accused of being witches. Hopkins personally supported the case against them.

The Bacons were tried and executed at the witch trials at Bury St Edmunds Assizes in 1645

Execution of witches. By Ralph Gardiner, 1655. ©British Library.

Execution of witches. By Ralph Gardiner, 1655. ©British Library.

Susan Manners and Jane Rivet, Copdock

Susan Manners and Jane Rivet were accused by three local people and two witch searchers. They were sent to Ipswich gaol before going on trial at Bury St Edmunds assizes in August 1645. Both were found guilty and executed. The village of Copdock later complained about having to pay the bill for the time the women spent in Ipswich Gaol.

A Lasting Legacy

End of the Witch Hunts

Matthew Hopkins faced growing scrutiny for profiting from witch trials, and the fact that despite many executions, misfortunes in communities continued. Hopkins died of tuberculosis in 1647 aged 27.

The Civil War came to an end in 1651, and economic growth and political stability meant life improved. The atmosphere of fear and distrust lessened. While some still believed in witches many became sceptical.

In 1660, King Charles II founded the Royal Society dedicated to scientific discovery. Their work helped explain phenomena that had once been blamed on witchcraft. This continued into the Age of Enlightenment from 1685, with an increasing focus on scientific research, logic, and social progress.

In 1736 all witchcraft laws were repealed. People who used magic could no longer be executed, but they could be fined or imprisoned.

Illustration from Discovery of Witches by Mathew Hopkins, 1647. ©The British Library

Illustration from Discovery of Witches by Mathew Hopkins, 1647. ©The British Library

The Heart of Suffolk Witch Trials