The World of Walton Burrell

Photographer, traveller, and deaf pioneer

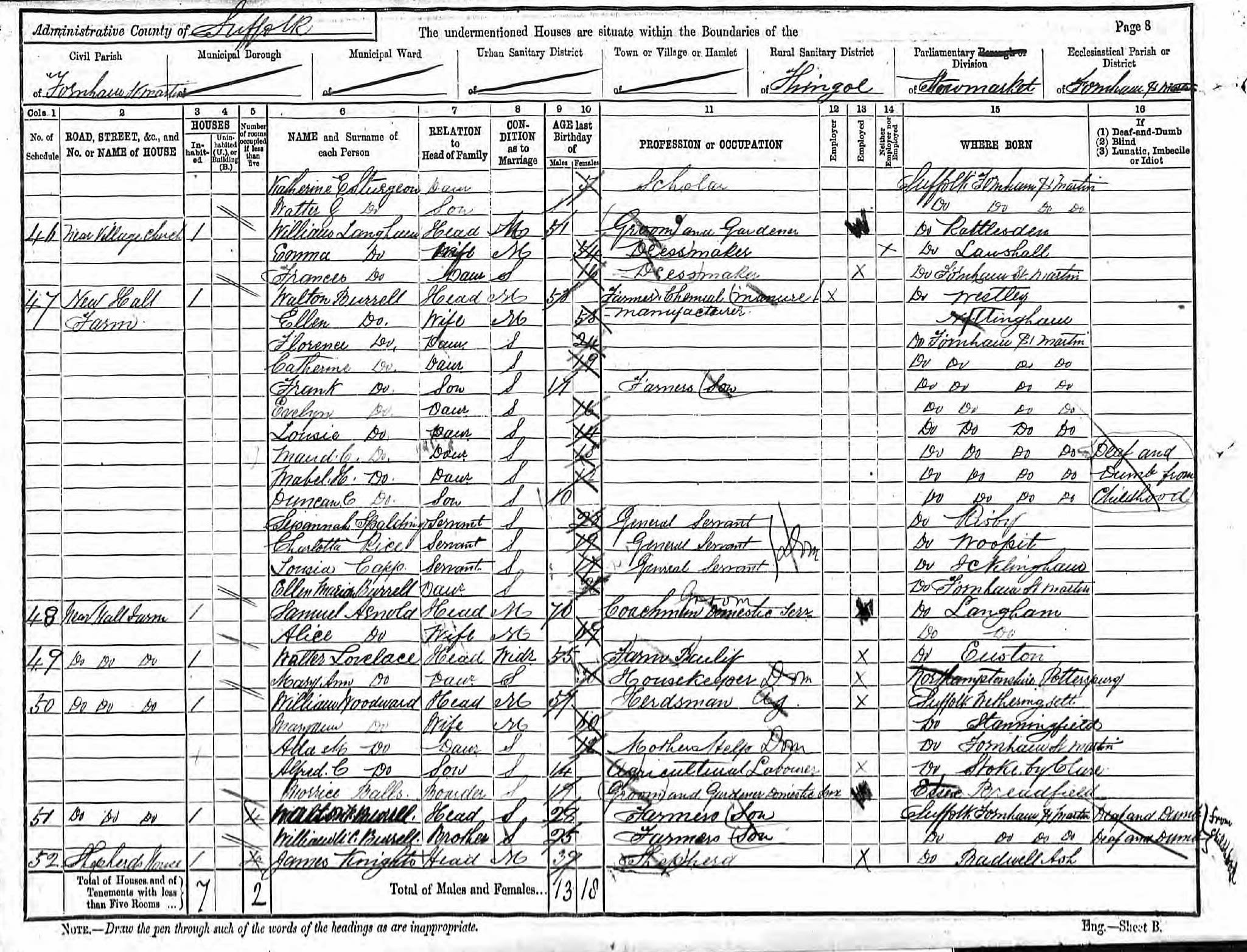

Walton Burrell was born in 1863 in Fornham St Martin, near Bury St Edmunds. He was the son of a wealthy farmer and his wife and was the eldest of 14 children.

Walton would grow up to be a prolific photographer; he estimated he took around 20,000 photographs over several decades, about 3,000 of which are today looked after by Suffolk Archives. He also travelled the world and was well-known locally for his overseas adventures.

Walton was born profoundly deaf, as were three of his siblings, William, Beatrice, and Clare. All of them were among the earliest members of what is today the British Deaf Association when it was founded in 1890.

Walton Burrell with his bicycle at West Stow (K997/8/9, courtesy of the Friends of Suffolk Archives)

Walton Burrell with his bicycle at West Stow (K997/8/9, courtesy of the Friends of Suffolk Archives)

Walton Burrell’s father and grandfather were both also called Walton Burrell, and both were gentleman farmers.

The eldest Walton lived at Westley Hall, a grand manor house, parts of which date back to the 16th century. The middle Walton established himself at New Hall Farm in Fornham St Martins, a few miles away from Westley Hall.

The middle Walton married Ellen Cowen in 1862, when they were both 24 years old. Walton described himself as a Gentleman Farmer. Their eldest child, the Walton of our story, was born a year later.

Walton was followed by 13 more children over the next several years. Two died very young.

The family seem to have had a comfortable life at New Hall Farm. When the 1891 census was taken they had three live-in servants and various other staff living close by. Some of the family’s older children, including Walton, were living in cottages on the farm estate.

Walton’s later photos show a comfortable upper-middle class family home, filled with furniture, ornaments, and books.

The house had a beautiful garden, the centrepiece of which was an ancient oak tree which supported a sturdy tree house and was often at the heart of family gatherings.

Walton, William, Beatrice, and Clare all went to a ‘Private School for Deaf Children of the Higher Classes’ run by a teacher called John Barber. Children boarded at the school, which was based in a series of large houses in north London. Walton began attending aged 4 and left at the age of 18.

The Burrell siblings were attending school at a time of fierce debate about the best way to educate deaf children. Some teachers advocated the use of sign language, while others were convinced of the benefits of the ‘oral method’, which taught deaf children to lip read and to speak, and strongly discouraged sign language.

John Barber was a staunch advocate for the oral method, so the Burrell children’s formal education would not have included sign language.

We do not know exactly how Walton communicated; there is evidence that he used lip reading and writing, but it seems likely that he would have used some basic signing or finger spelling when with other deaf people.

Walton started taking photos in 1883, aged about 20. He may be the earliest deaf photographer in the UK. He learned from John Palmer Clarke who was a photographer on Angel Hill in Bury St Edmunds. Walton’s photos may also be the earliest in the UK of named deaf individuals.

Walton’s earliest photographic subjects were his family and friends. His sisters seem to have been the most willing to pose and dress up for his pictures.

He visited his old school, where Beatrice and Clare were still pupils, and took pictures of the staff and students.

The gallery below shows some of his earliest photos, taken in the 1880s. Click on an image to expand it.

Staff and pupils at John Barbers school. John Barber is the man with the beard, seated on the right. Beatrice Burrell stands behind him and Clare Burrell is sitting on the ground in front of him. (K1103)

Staff and pupils at John Barbers school. John Barber is the man with the beard, seated on the right. Beatrice Burrell stands behind him and Clare Burrell is sitting on the ground in front of him. (K1103)

Walton's sisters Beatrice, Clare, and Florence (K1103)

Walton's sisters Beatrice, Clare, and Florence (K1103)

Walton's sisters Beatrice, Clare, Florence, and Nellie in fancy dress

Walton's sisters Beatrice, Clare, Florence, and Nellie in fancy dress

Walton's sisters Katie, Beatrice, Louise, and Evelyn (K1103)

Walton's sisters Katie, Beatrice, Louise, and Evelyn (K1103)

Walton Burrell (right) with a cycling group at the Red Lion, Icklingham (K1103)

Walton Burrell (right) with a cycling group at the Red Lion, Icklingham (K1103)

Walton's parents at the dining table in Hall Farm (K1103)

Walton's parents at the dining table in Hall Farm (K1103)

Walton's Uncle Edwin and sisters Mabel, Louise, Beatrice, Clare, Katie, and Evelyn 'Waving goodbye to the 19th century' on New Year's Eve 1900 (K1103)

Walton's Uncle Edwin and sisters Mabel, Louise, Beatrice, Clare, Katie, and Evelyn 'Waving goodbye to the 19th century' on New Year's Eve 1900 (K1103)

Walton with his sister Nellie and their parents (K1103)

Walton with his sister Nellie and their parents (K1103)

The other characters which appear in Walton's early photos are the family's pets, particularly his red squirrel, Bobbie, which he raised from a kit. Walton seems to have been very fond of Bobbie - there are entire pages of his albums filled with pictures of the squirrel.

Bobbie the squirrel being hand fed (K997/10/13, courtesy of the Friends of Suffolk Archives)

Bobbie the squirrel being hand fed (K997/10/13, courtesy of the Friends of Suffolk Archives)

Walton with his pet red squirrel, Bobbie (K1103)

Walton with his pet red squirrel, Bobbie (K1103)

The majority of Walton's photographs which are today looked after by Suffolk Archives date from the First World War. These are found mainly in an album which was purchased by the Friends of Suffolk Archives (K997). They form an incredible record of life on the Home Front in West Suffolk.

Walton must have met thousands of soldiers, and many of them were happy to pose for pictures. Walton sold postcards of some of these pictures, perhaps for soldiers to send home to their loved ones.

One of the first effects of the war to be seen in West Suffolk was the sudden arrival of soldiers. They took up residence in camps all around while they underwent training. Walton must have been a regular visitor to some of these camps, capturing the soldiers off-duty.

It was not long before wartime hospitals started to open, often in large private residences. Walton was a regular visitor to several of the hospitals close by, particularly Ampton Hall, which he visited over 1000 times in two years.

This photo shows Walton in the middle of the back row, without his moustache, surrounded by Australian soldiers who were recuperating at Ampton Hall hospital.

Walton's photographs from the hospitals show the extent of the injuries which some of the men had received. The man on the far left in a wheel chair is Trooper Ben Squirrell, who had lost both his legs and was photographed several times by Walton. He was from Bildeston in Suffolk and was one of five brothers who fought in the war. He joined underage and lost his legs as a result of wounds and frostbite he suffered in Gallipoli.

The Burrell family invited soldiers from the local hospitals to New Hall Farm for socialising and sports, including ladies vs soldiers cricket.

The women of the family took part in fundraising efforts supporting wounded soldiers and prisoners of war. This photo of a fundraising drive for Suffolk Prisoners of War was taken on Abbeygate Street in Bury St Edmunds, outside The Nutshell pub. It includes Walton's sisters Beatrice, Clare, Louise, Mabel, and Evelyn.

Walton also captured damage done by Zeppelin raids on Bury St Edmunds. This photograph shows the aftermath of an air raid on the Buttermarket in April 1915.

Walton also photographed the crowds which came to see the damage. He must have climbed a ladder to capture this shot.

After the war Walton photographed many of the local war memorials. He took this photo at the unveiling of the war memorial in his home village of Fornham St Martin on 3rd April 1921.

Walton was one of the very first members of the British Deaf and Dumb Association (BDDA, now the British Deaf Association) when it was founded in 1890. The Association was formed to advocate for the rights of deaf people, at a time when they were often not consulted on matters which directly affected them. It was partly a response to moves to remove sign language from education for deaf children.

The meeting shown in this photograph took place in Leeds in 1887, and may well have been part of the discussions which led to the founding of the BDDA. Walton's caption for the photo tells us that all but three of the people in the photo were deaf.

Walton, who would have been about 23 at this time, is standing next to Francis Maginn, one of the founders of the BDDA. Maginn lost his hearing aged 4 due to Scarlet Fever. He had studied at a university for the deaf, Gallaudet, in America, and made it his life's work to improve quality of life for the deaf in the UK. His vision included using sign language as part of deaf education.

Also pictured is Reverend William Blomefield Sleight, who became the first President of the BDDA. He was hearing, and the son of the Headmaster of the Brighton Institution for the Deaf and Dumb. He led the BDDA until 1918.

The photograph also includes Charles Kerney who founded a school for the deaf in Evansville, Indiana, in 1886, and his wife Annabel, who had lost her hearing as a child due to meningitis.

Walton's world tours

Walton was well known locally during his lifetime for his adventurous travels:

‘He had numerous interesting experiences in many countries of the world. Holland, Belgium, France, Spain, Portugal, Italy, Greece, Palestine, Egypt (five times), Arabia, India, Ceylon, Malay States, Japan, Australia, Algeria, Norway and Corsica were some of the places in which he indulged his love for travel.’

Walton also learned four languages – French, German, Italian, and Spanish – which helped him to make his journeys independently.

His travels were so unusual that in 1931, after a trip to Australia, the Bury Free Press despatched a journalist to interview Walton. Walton travelled to Australia by ship, on the steam ship Bendigo, leaving London on 10th July.

The ship had several ports of call, including Melbourne, where Walton was reunited with Miss Ingram, who had been a nursing Sister at Ampton Hall Hospital during the First World War. She showed him round the city and Walton described having a ‘splendid time’.

In Perth Walton described his ‘first sight of Australian scenery – lovely wattle trees in full blossom (called mimosas in England).’ In Adelaide he ‘went over the beautiful town and then to Mount Lofty which was covered with wattle trees in blossom and the scent was very strong’.

His ultimate destination was Brisbane, where he had ‘a splendid welcome’. Some cousins came to meet him, and he also met up with Ernest Smith, who had been a patient at Ampton Hall. Ernest took Walton out in his car, touring ‘Australian bush fruit farms, watering places, etc’.

Walton stayed in Brisbane for two months with his cousin Lilian. Excursions included visits to mountains in New South Wales, and Walton described seeing ‘many fields of strawberries, and Princess of Wales violets, and oranges, mandarin (tangerine) and lemon trees everywhere, also bananas and pineapples’.

On the voyage back ‘There were all kinds of entertainments on the ship such as dancing, cinemas, games, treasure hunts, horse racing, sports, fancy dress balls, etc., and I did not like having to get out at Tilbury after the glorious time I had experienced for seven weeks’.

It is Walton’s trip to Australia for which the most detail survives, but we can also find him in travel records going to Yokohama, Japan, in 1933, and to Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1936. The 1936 trip was an extensive cruise which took in a huge number of ports of call, including Madeira, Miami, Cuba, Panama, Hawaii, San Francisco, the Grand Canyon, Mexico, and Guatemala. One of the three of Walton’s albums at Suffolk Archives includes photographs and postcards from this trip. Walton was 76 by this point, and his drive to travel and see new sights seems undiminished.

Walton on board a cruise ship in Hawaii in 1936 (K1349)

Walton on board a cruise ship in Hawaii in 1936 (K1349)

Walton (centre back row) with a group in St Helier, Jersey, Channel Islands, in 1886. Seated on the left of the middle row is Edgar Jepson, who became a well-known author.

Walton (centre back row) with a group in St Helier, Jersey, Channel Islands, in 1886. Seated on the left of the middle row is Edgar Jepson, who became a well-known author.

Soldiers and civilians outside the Culford Arms, Ingham. The solder in the wheelchair is Australian soldier Ernest Smith, who was at Ampton Hall Hospital for 8 months and who Walton later reconnected with in Australia. (K997/23/5, courtesy of the Friends of Suffolk Archives)

Soldiers and civilians outside the Culford Arms, Ingham. The solder in the wheelchair is Australian soldier Ernest Smith, who was at Ampton Hall Hospital for 8 months and who Walton later reconnected with in Australia. (K997/23/5, courtesy of the Friends of Suffolk Archives)

Sister Ingram (right), who Walton first met at Ampton Hall during WWI, and later reconnected with in Australia (K997/68/9, courtesy of the Friends of Suffolk Archives)

Sister Ingram (right), who Walton first met at Ampton Hall during WWI, and later reconnected with in Australia (K997/68/9, courtesy of the Friends of Suffolk Archives)

The route and ports of call of a cruise Walton went on in 1936 (K1349)

The route and ports of call of a cruise Walton went on in 1936 (K1349)

Walton's place in Deaf History

By Stephen Iliffe, photographer and creator of Deaf Mosaic

Walton R. Burrell has a very special place in the history of the British deaf community. Not only as the earliest-known working deaf photographer, but also as one of the first advocates for empowering deaf people. During the mid-Victorian era, Walton was an outlier: an educated deaf man before the arrival of compulsory state education when most deaf people were illiterate. With few adult deaf role models to look up to, Walton had to improvise his own way in life. His best works are early examples of what we would recognise today as ‘photojournalism’. They offer early tangible evidence that, with the right support, ‘deaf people can do anything’. As a founder-member of the British Deaf and Dumb Association, Walton was also one of a small group of people to actively challenge Parliament to improve legal rights for deaf people. The re-discovery of Walton’s story by Suffolk Archives is a milestone in our national deaf history.

The Deaf Perspectives project

Walton’s life story and photographs have been the inspiration for the Deaf Perspectives project. Suffolk Archives have worked with Orchestras Live, Suffolk Music Hub, Britten Sinfonia, and others to run creative activities with Westgate Community Primary School and King Edward VI School. Both schools have Deaf Resource Bases and are in Bury St Edmunds. 26 students aged 5 to 15 have taken part in the project, which has included archive workshops, photography and film workshops, and music workshops with composer James Redwood and Deaf flautist Ruth Montgomery. The project culminated with a concert in which the students performed new music they had created with James and Ruth alongside Britten Sinfonia. A film of the concert is available to watch on the Suffolk Archives YouTube channel.

The students have thrown themselves into the project and report that it has increased their confidence and sense of belonging at school. The concert audience told us they found the performance moving and inspiring, and that the project highlighted that ‘Archives not only conserve the past but make things happen in the present too’.

Students from Westgate Community Primary School and King Edward VI School visiting Suffolk Archives to see Walton's photos

Students from Westgate Community Primary School and King Edward VI School visiting Suffolk Archives to see Walton's photos

Creating music inspired by Walton's photographs

Creating music inspired by Walton's photographs

Walking in Walton's footsteps

Inspired by Walton's photographs, the Deaf Perspectives project students have been improving their own photography skills. Working with the Offshoot Foundation they have learnt the essentials of composing, lighting, and shooting their own pictures.

Westgate Community Primary School Deaf Resource Base (DRB) students

Westgate Community Primary School Deaf Resource Base (DRB) students

What still needs to change for d/Deaf people today?

Students from the Deaf Resource Base at King Edward VI School in Bury St Edmunds tell us here what they think still needs to change for d/Deaf people today.

William

I think that we need better hearing technology so that we could hear better. Furthermore, I think everyone should be able to sign as not every deaf person can talk or hear speech. If everybody could sign this would mean that people can communicate with other deaf people around them.

Esmee

I think that if everyone could sign it would be good because everyone would be able to talk to each other whether you are deaf or not.

I also think it would be nice if people had a better understanding of Deaf people, like knowing you should not mumble or walk about when you are talking because it would help me.

Ellie

Everyone to start signing when they are a baby because normally kids from 2-3 year olds gets cochlear implants/hearing aids straight away before they learn their own precious sign language.

For people NOT to say ‘I’ll tell you later’ if we missed something. You should repeat what you said, it just frustrates us about what if you don’t like us?

Kai

What still needs to change for Deaf people I think is to make all jobs available for everyone… I also think that for hearing people to have a better understanding of what it’s like to be deaf because it would be nice that people can come up to deaf people and show us that they know about deaf people and BSL, and know not to cover their mouth or mumble. If they didn’t do that it would make life much easier.

Acknowledgements

This display has been produced with the help of research by David Addy, Steve Kentfield, Stephen Iliffe, and Jemima Buoy.

It has been produced as part of the Deaf Perspectives project, which has been supported by numerous partners.