‘In the national interest’

Stories from the Bury St Edmunds Local Military Tribunal, 1916-1918

"If I have to go it would be absolute ruin to me"

Harold Charles Cracknell, Carter and General Dealer

(EE500/D/12/22/1/497)

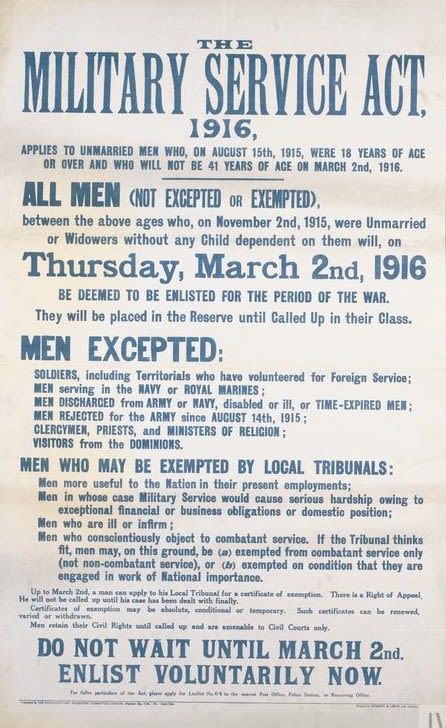

The Introduction of Conscription

By the middle of 1915 the British Army needed 130,000 new recruits every month to replace those being killed or injured.

Britain had traditionally relied on volunteers for military service but not enough were coming forward. One last attempt was made in autumn 1915 to raise volunteers, the Derby Scheme. This campaign strongly encouraged men to ‘attest their willingness to serve’. The men who responded were put into groups. Younger, single men would be called first, and older and married men would be called later.

The Derby Scheme did not raise enough volunteers. The only alternative was to introduce conscription – requiring men to serve in the military whether they wanted to or not.

Two Military Service Acts were passed in 1916 which made every male British subject aged 18-41 liable to be called for military service (in 1918 the upper age limit was increased to 51). It was an unprecedented expansion of the influence of the state in the lives of individual subjects.

The government knew that introducing conscription would not be popular. To soften the impact, the Military Service Acts included four grounds on which men could ask for exemption from military service:

- That they were already doing essential war work

- That military service would cause them severe hardship

- Ill health

- Conscientious objection

Over 2,000 Local Military Tribunals were set up across the country to hear applications for exemption. Men could apply to them to ask for their military service to be delayed, or to be exempted completely.

Poster advising on the terms of the Military Service Act 1916 (Imperial War Museum)

Poster advising on the terms of the Military Service Act 1916 (Imperial War Museum)

How the Tribunal process worked

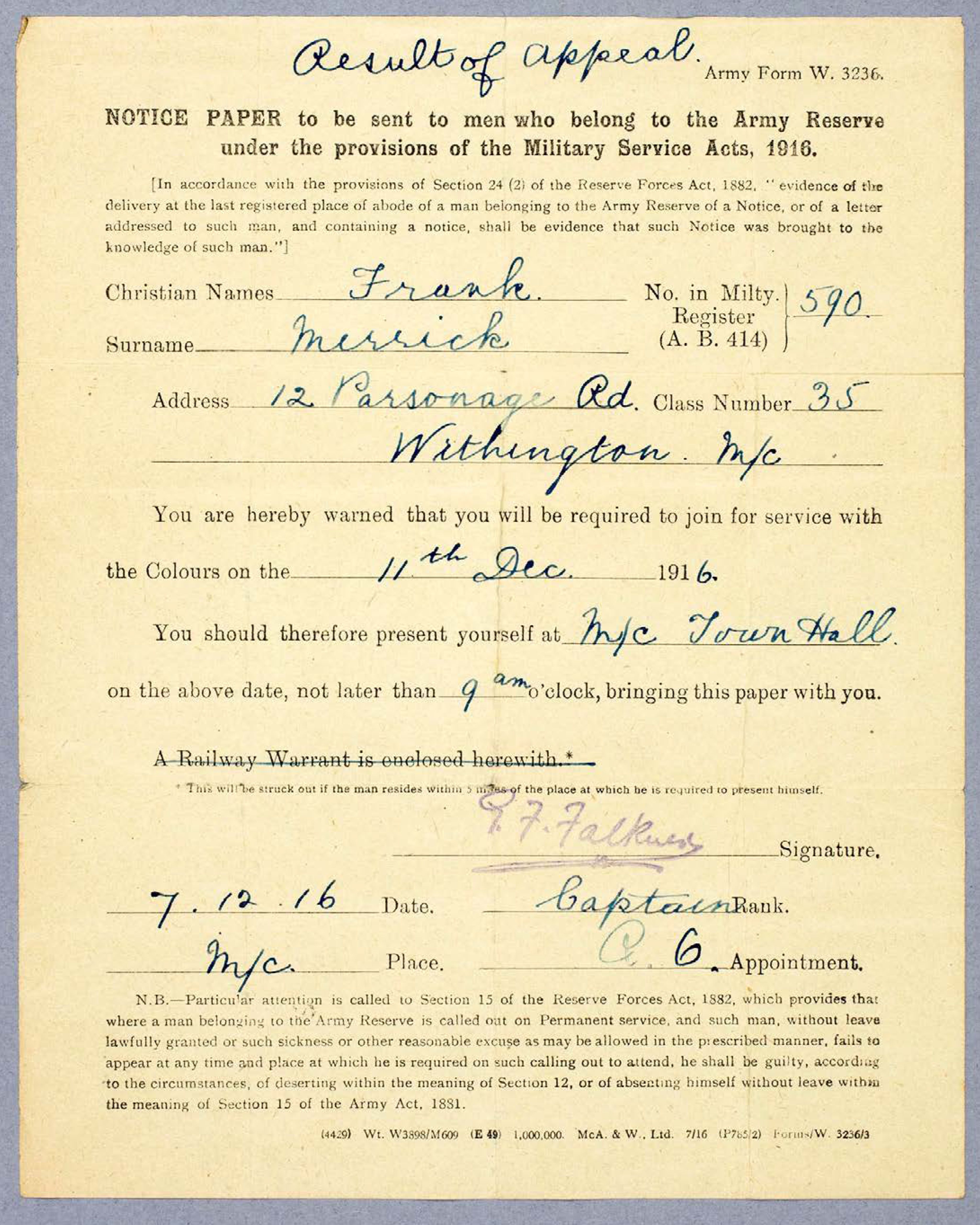

Call-up notice

Man receives papers telling him he has been called up for military service.

Call-up notice for Frank Merrick, University of Bristol Special Collections, courtesy of the Merrick family

Call-up notice for Frank Merrick, University of Bristol Special Collections, courtesy of the Merrick family

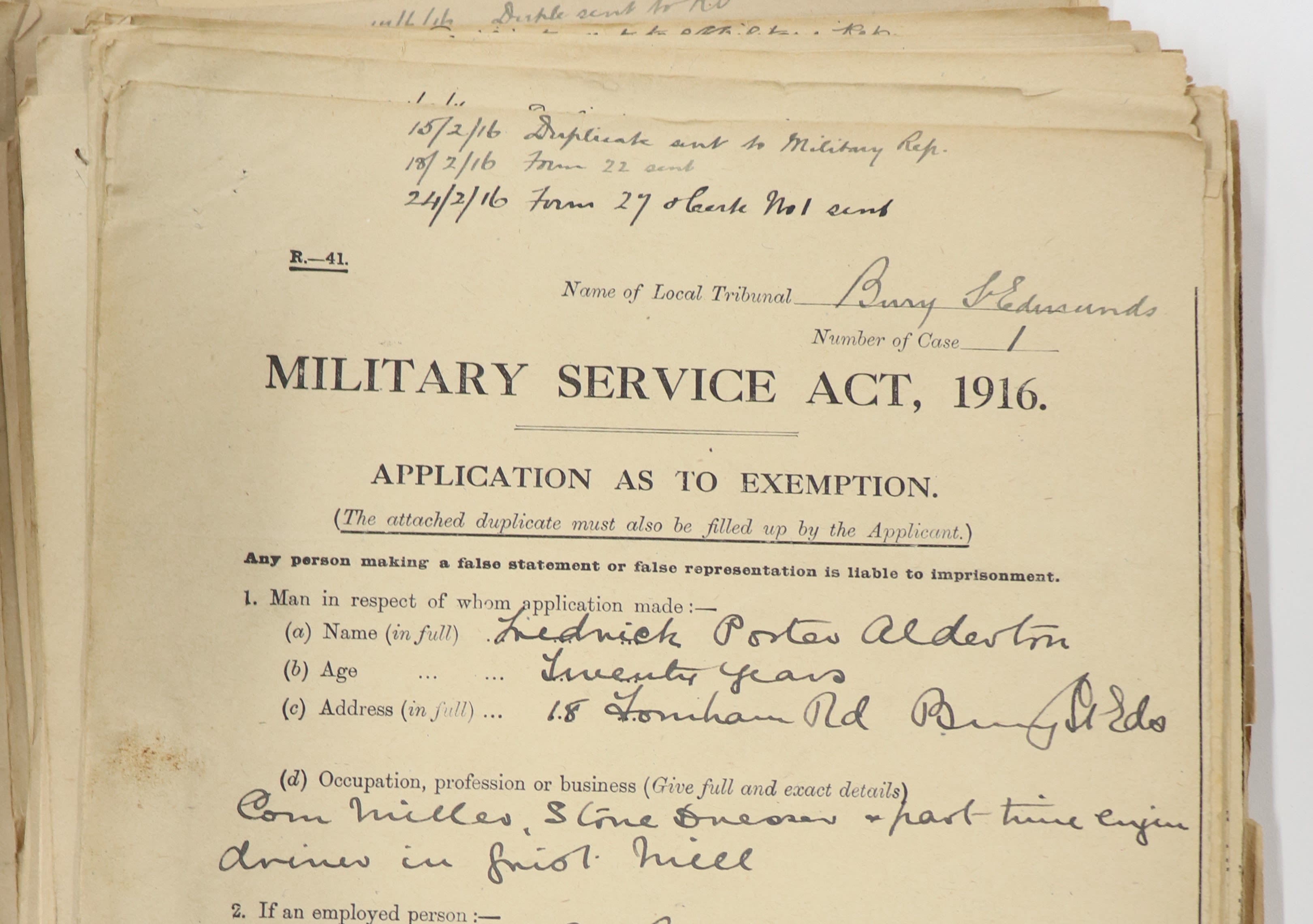

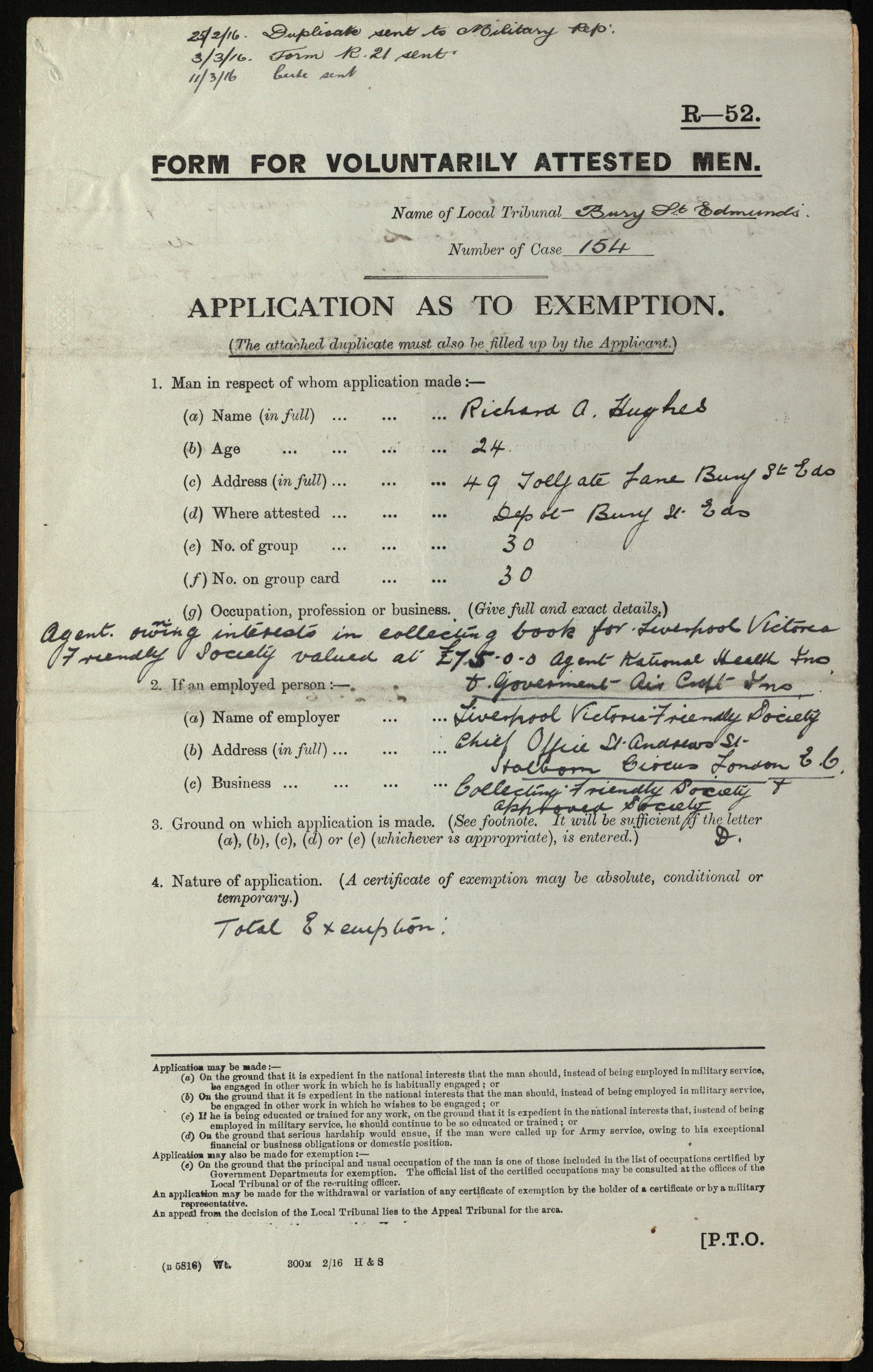

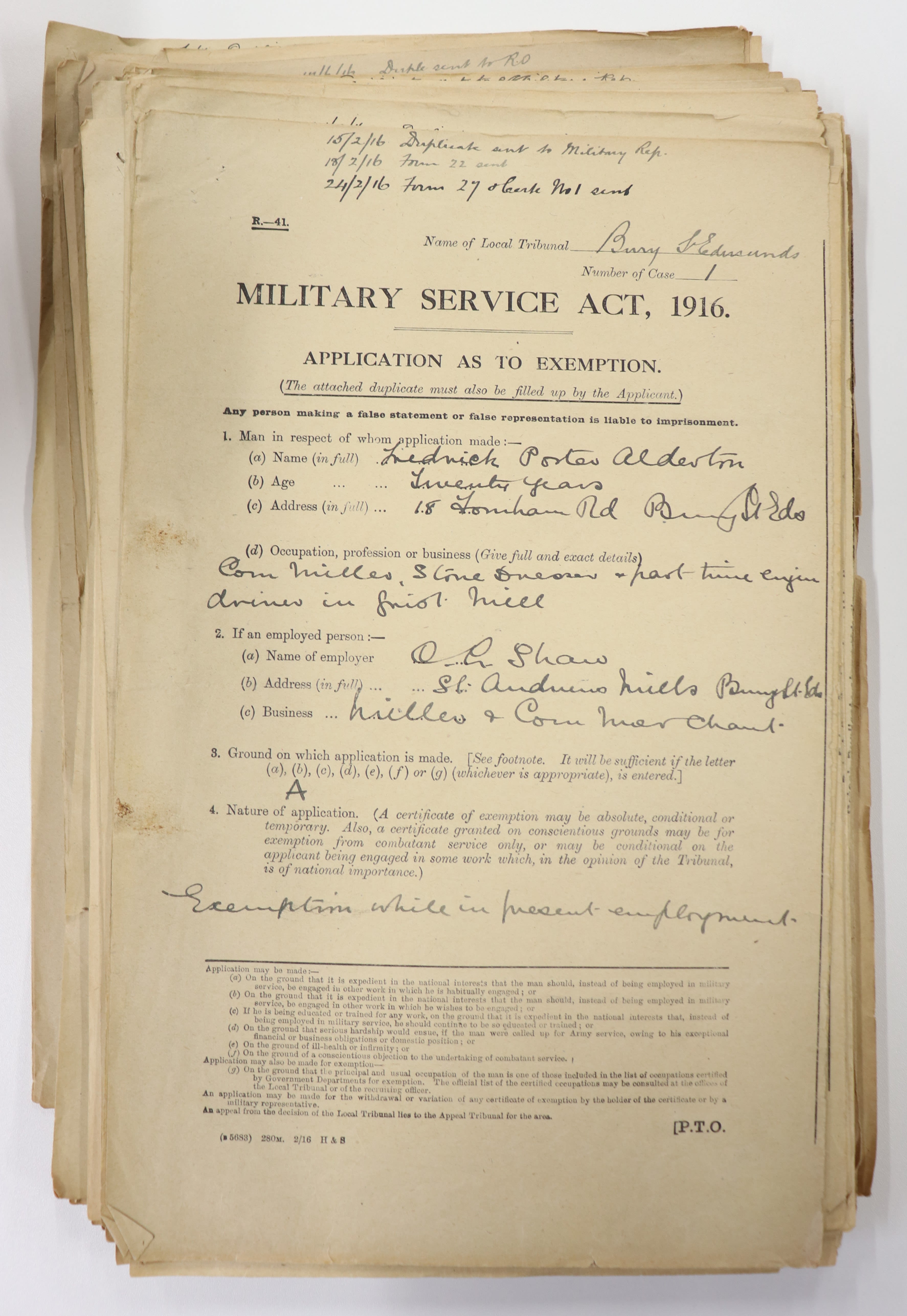

Application form

A man - or his employer - fills in a form giving reasons why he should be exempted from military service.

Application for exemption for Richard Hughes, Suffolk Archives (EE500/D/12/22/1/154)

Application for exemption for Richard Hughes, Suffolk Archives (EE500/D/12/22/1/154)

Military Representative's Comments

Someone representing the military comments on the case.

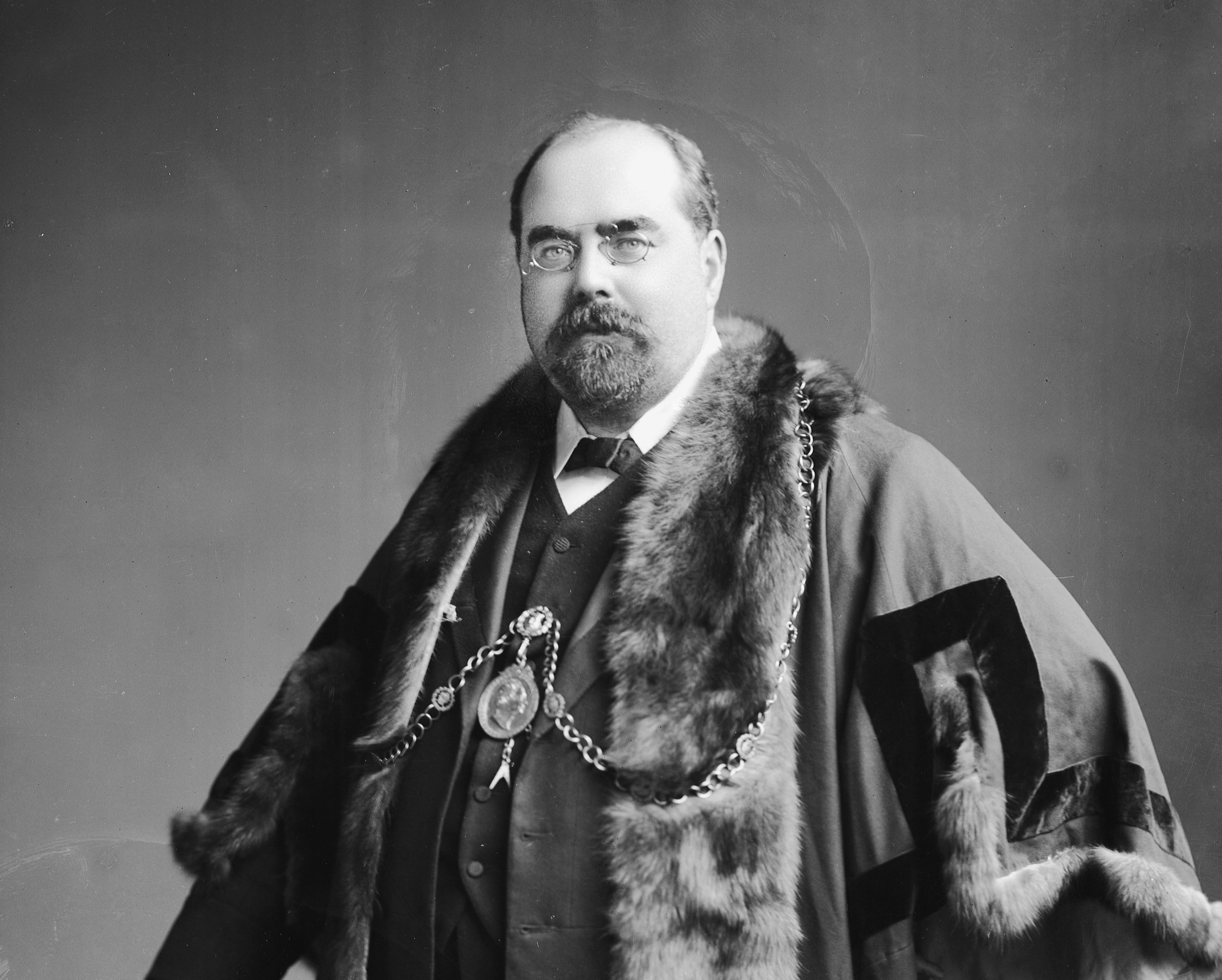

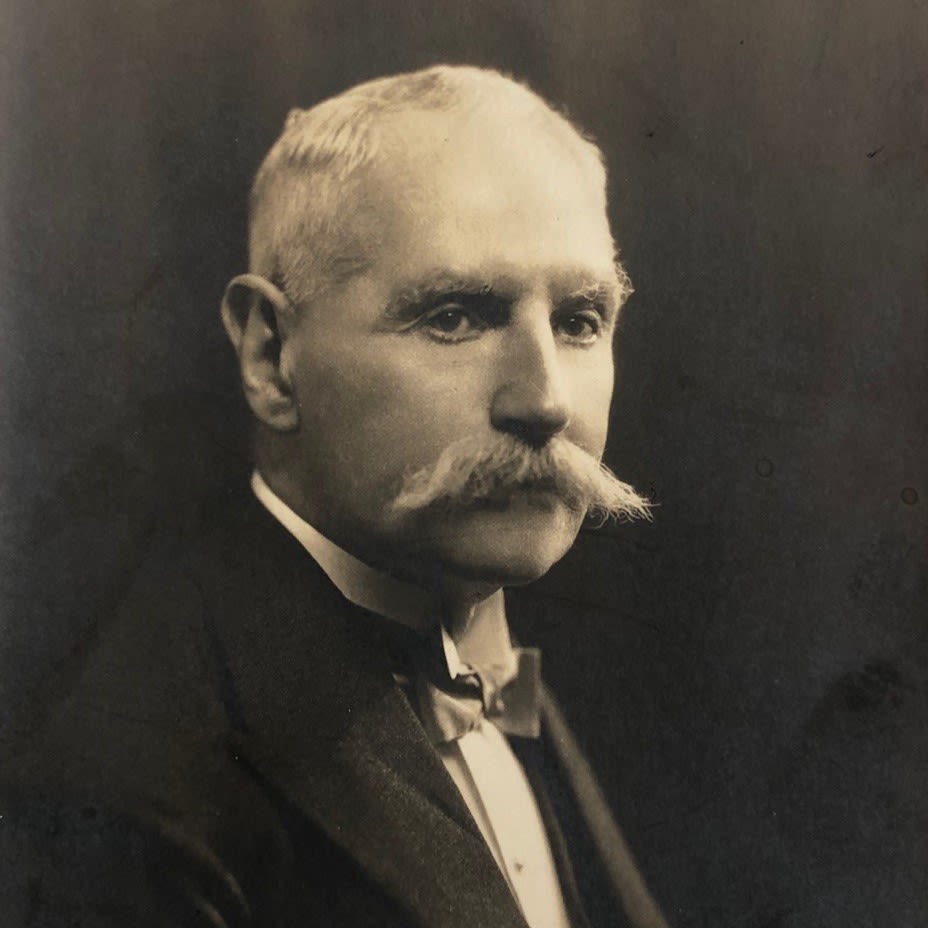

Gerald Cadogan, 6th Earl Cadogan, one of the Military Representatives in Bury St Edmunds, National Portrait Gallery

Gerald Cadogan, 6th Earl Cadogan, one of the Military Representatives in Bury St Edmunds, National Portrait Gallery

Tribunal meeting

The Tribunal panel meets at the Town Hall to make a decision on each case.

Bury St Edmunds Town Hall, where the Tribunal hearings took place (K505/1219, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

Bury St Edmunds Town Hall, where the Tribunal hearings took place (K505/1219, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

Appeals

If an applicant or the Military Representative was unhappy with the result they could appeal to a higher level Tribunal.

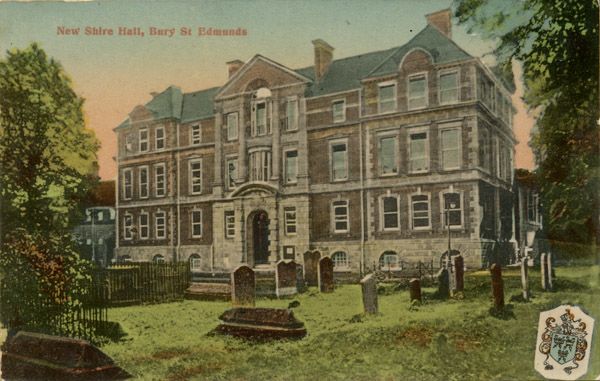

Shire Hall in Bury St Edmunds where the West Suffolk County Appeal Tribunal met (Suffolk Archives, K511/716)

Shire Hall in Bury St Edmunds where the West Suffolk County Appeal Tribunal met (Suffolk Archives, K511/716)

The Tribunal heard cases from men who had attested under the Derby Scheme (‘Attested men’) and men who had not ‘Non-attested men’.

Men were put under enormous pressure to attest through the Derby Scheme. Some did so with the expectation that they could apply for an exemption later. Other men who attested may well have been prepared to serve but their employer did not want to lose them.

“I am the only one left in the family and the canvassers said if I was attested I should stand a better chance, they said I should never be wanted at all”.

Just within the first 6 months of 1916 there were nearly 750,000 applications to the Tribunals. With so many people having experienced the Tribunal system one might expect them to feature prominently in First World War histories, but they are rarely mentioned. In 1921 the government ordered that, due to their sensitive nature, the vast majority of the records be destroyed.

In recent years Tribunal records which escaped destruction have been identified, including the records from the Bury St Edmunds Tribunal. The records provide a fascinating insight into the society, industry, and economy of Bury St Edmunds during the First World War and the conflict between local interest and national policy.

The Local Tribunals had to be set up quickly. Government instructions said that it was of the “utmost importance that the Tribunals should be constituted so as to command public confidence” (Local Government Board Circular R36).

The first panel members in Bury St Edmunds were drawn from the local council. Several were also prominent businessmen.

It was not unusual for the panel members to have a professional or personal connection to the applicants. They would excuse themselves for those cases.

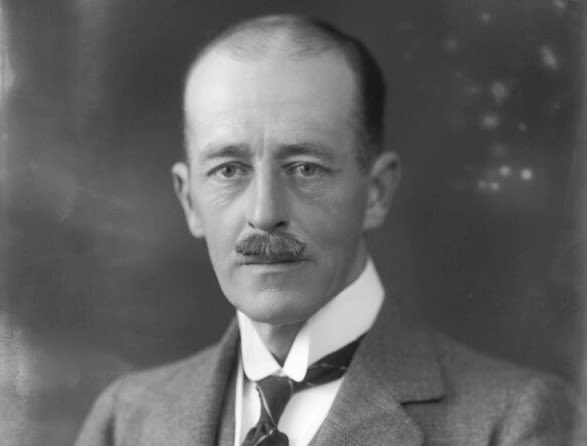

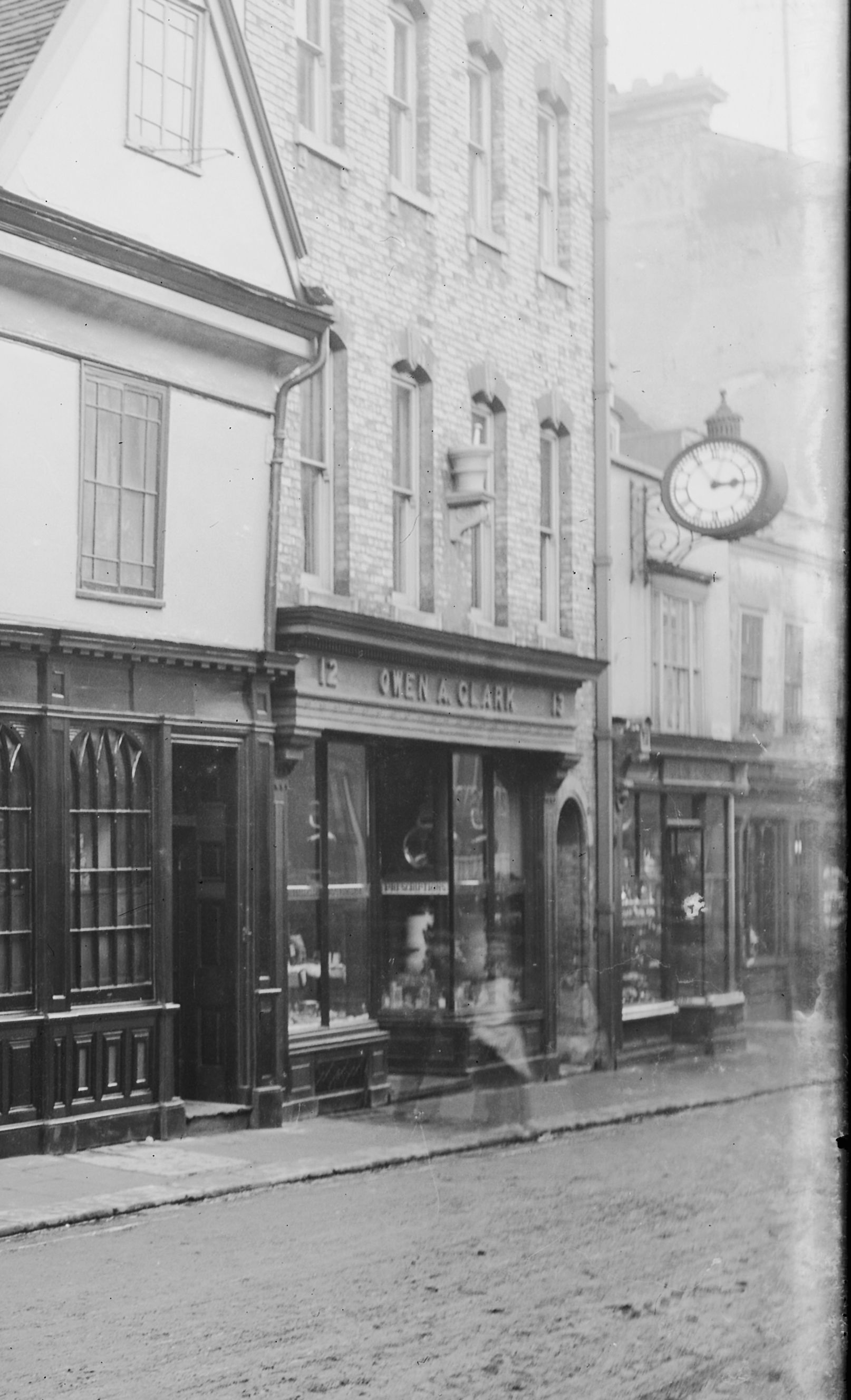

Owen Aly Clarke

The first Chairman of the Tribunal. Clarke was the Mayor in 1916, an Alderman, and Justice of the Peace. He was also a chemist and druggist with a business on Abbeygate Street and a Freemason.

Image: Owen Aly Clarke when he was mayor (K505/3188, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

Alexander Mitchell

Deputy Mayor, an Alderman, a Magistrate and former Mayor. Originally from Scotland, he had moved to Bury in about 1880 to manage the town’s gas works.

Image: Alexander Mitchell as Mayor, courtesy of West Suffolk Council

John Ridley Hooper

A Councillor, Justice of the Peace and leather merchant. He had a son serving in the military.

Image: John Ridley Hooper (K505/639, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

John G. Oliver

A Conservative Councillor and former Magistrate and Mayor. He was also a wine and spirit merchant with a business on the Cornhill. He had a son serving in the military.

Image: John Oliver as Mayor, courtesy of West Suffolk Council

Henry Bankes Ashton

A local solicitor. Ashton's firm helped applicants prepare their cases hearings at local Tribunals and the West Suffolk Appeal Tribunal. Pressure of work caused him to resign from the Bury St Edmunds Tribunal in July 1916.

Image: Henry Bankes Ashton, courtesy of Rob Ashton

Dr William James Caie

William Caie was a medical doctor originally from Scotland. He served as a temporary Major in the 2nd East Anglian Field Ambulance and was a committed Freemason.

Image: Dr William Caie (K505/3518, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

At the earliest meetings of the new Tribunal it was agreed that it was necessary to have representatives of Bury’s working men on the panel. Additional men were recruited to fulfil this role.

“Most of the men fighting in this war were drawn from the working classes, therefore they ought to be well represented.”

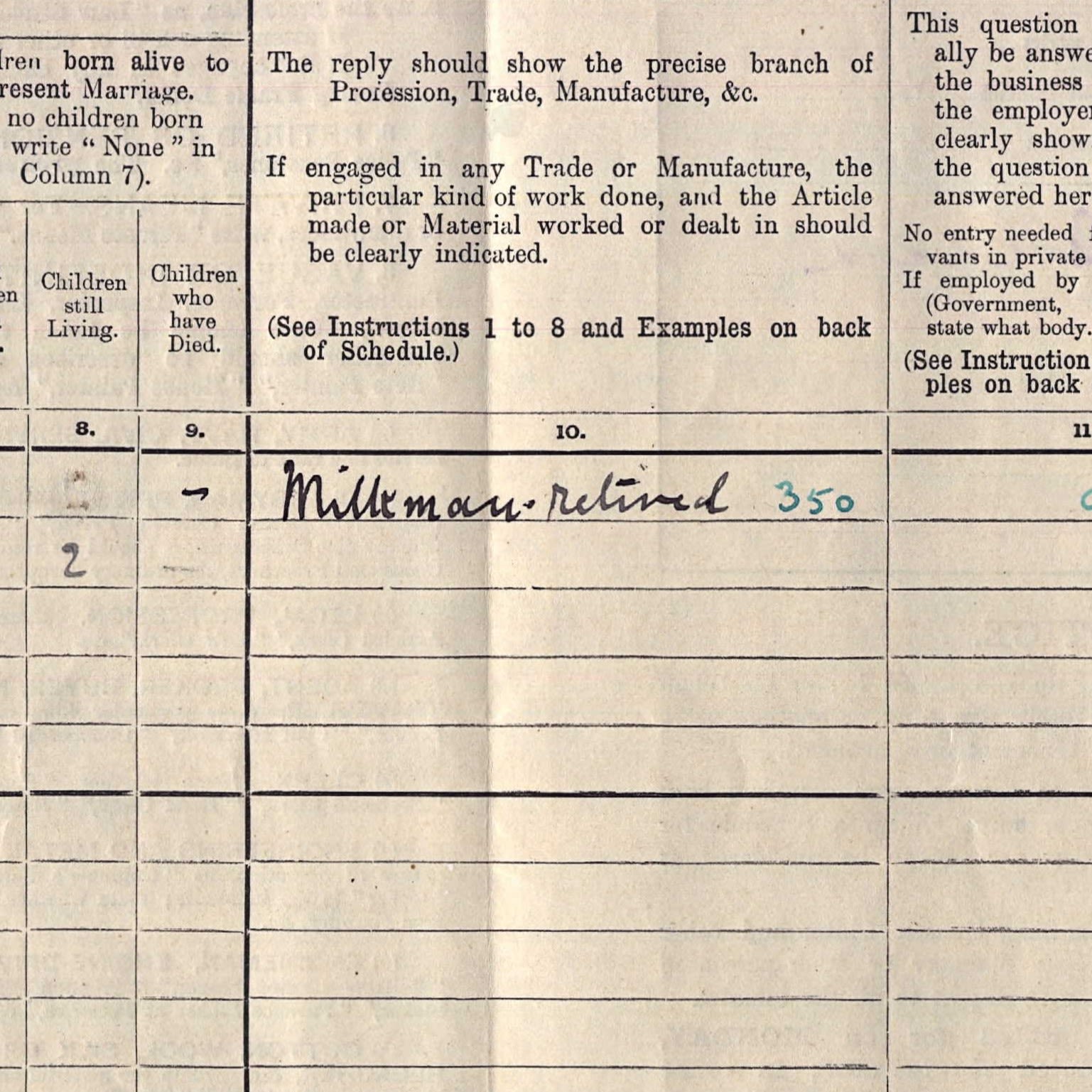

Edward Abner Goddard

A councillor for Westgate Ward and a progressive (Liberal) party candidate who worked as a merchant and milkman.

Image: Edward's entry in the 1911 Census

Ebenezer John Daniels

An engineer’s fitter, who worked for Robert Boby.

Image: Photo of Ebenezer John Daniels published with his obituary in the Bury Free Press, 26th March 1927

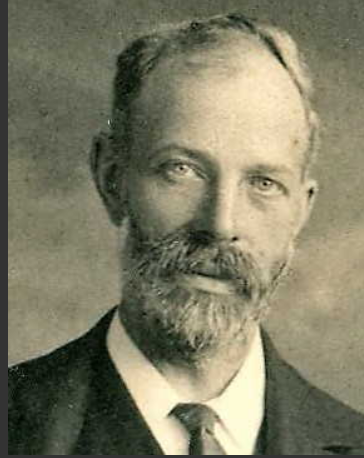

Robert Geard

From Somerset, a carpenter by trade, who had become a foreman for H. G. Frost, a Bury builder.

Image: Ancestry

William Sparks James Simkin

A journalist for the East Anglian Daily Times.

Image: Bury Free Press, 19th July 1919

Robert Geard and Ebenezer John Daniels were particularly active advocates for fair treatment for working men. Robert Geard emphasised the comparative levels of hardship faced by working men who were denied exemption “leaving no bank balance behind them” and often “having to pawn things in order to enable them to go”. Employers and businessmen, in contrast, could call upon a network of friends, family, and trusted employees to continue to run their businesses (Bury Free Press, 1 July 1916).

E. J. Daniels was concerned to ensure that no bargains were made by employers with the military without the knowledge or consent of the men affected, as well as trying to ensure that all men knew that they had a right to make a personal application for exemption, even if their employer had also made an application on their behalf.

“Men should know that their freedom could not be bartered away.”

Setting a patriotic example

It was not unusual for Tribunal panel members to have a connection with the men whose cases they were considering. Sometimes they even applied for their own employees.

27-year-old single man Sydney Frank Pamment was an experienced chemist’s assistant. His employer was chemist and Tribunal panel member Owen A. Clarke. Clarke applied for absolute exemption for Sydney on the grounds that he was 'absolutely necessary' to the business. The Tribunal granted temporary exemption.

A Military Representative later applied to have this temporary exemption withdrawn. Instead, the Tribunal improved Sydney's position, granting him conditional exemption.

However, in response to a War Office Appeal for more men in October 1916, Owen A. Clark made an extraordinary gesture:

“The Mayor [Clarke] asked the Tribunal to grant him a cancellation of the certificate of exemption. As Mayor and as their chairman, he felt that in order to get the four hundred thousand men exempted to do their duty he could not preach what he did not practise”.

Sydney's exemption was cancelled. He married later that month before joining up.

He survived the war and returned to his old job with Owen A. Clarke.

Owen Aly Clarke's chemist shop on Abbeygate Street (K505/2824, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

Owen Aly Clarke's chemist shop on Abbeygate Street (K505/2824, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

The Military Representatives

The War Office appointed Military Representatives to attend the local tribunals on behalf of the local recruiting officer. They were supported by the expertise of a Local Advisory Committee, chosen for their knowledge of the local economy.

Unlike the Panel members, the Military Representatives in Bury were men of independent means. The two longest serving and most influential Military Representatives appointed to the Bury Military Service Tribunal were Lord Cadogan of Culford and Charles Henry Bramley Firth of Saxham Hall.

Culford Hall (K505/1545, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

Culford Hall (K505/1545, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

Saxham Hall (K505/2500, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

Saxham Hall (K505/2500, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

Their role – to conscript eligible men – frequently brought them into conflict with the civilian Tribunal panel.

This graph shows what men or their employers applied for, what the Military Representative recommended, and the decision made by the Tribunal. It shows how the Tribunal often did not follow the Military Representative's suggestion. For example, in 286 cases the Military Representative thought the man should get no exemption at all, but the Tribunal only decided on no exemption in 100 cases.

The Military Representatives had the right to appeal Tribunal decisions. They could also make their own applications to ask for exemptions which had already been granted to be withdrawn.

We can discover the views of the Military Representatives through the comments they made on cases.

On the case of a hairdresser:

“You would soon pick up your business when you came back […] There would be plenty of hair growing by the time you get back.”

On the case of a dentist:

“People can wait for professional attention to their teeth until after the war”.

On butchers' slaughtermen:

“You will have to combine your slaughtering for the period of the war. It is impossible to leave all these young men as slaughterers all over the town”

On dairy work:

“Have you employed women to milk cows? […] You try those women. They are very clever with the cows.”

Chronology of cases

The Bury St Edmunds Tribunal met 56 times between January 1916 and October 1918. Their busiest period was spring 1916.

A final spike in case numbers occurred in spring 1918. There was an increased need for new recruits as the German Spring Offensive crashed through Allied lines on the Western Front. A third Military Service Act had raised the age limit for military service to 51 and restricted exemptions on occupational grounds. This made thousands more men eligible for conscription.

The case files from 1918 give a sense of a desperate need for men.

Age profile

Recruitment in 1914-1915 had targeted younger, unmarried men. By 1916, supplies of these men were drying up. Most of the men who went through the Tribunal process in Bury were in their 30s.

Looking at the men who had attested through the Derby Scheme (Voluntarily Attested) and the Non-Attested men we can see some interesting differences in their age profiles. The Non-Attested group includes higher numbers of both younger and older men. The fact that all men over 41 are in the Non-Attested group is explained by the fact that men in this age category only became eligible for military service in spring 1918. The youngest men we see in this group may have not been old enough to volunteer before conscription came in.

The youngest applicants

The youngest applicants to the Tribunal were two 17-year-olds, both students at the East Anglian School in Bury. Robert Gore's case was heard in June 1916. He asked for time to finish his exams and to help with the harvest on his family's farm in Berkshire. He was granted temporary exemption until 30th September 1916. He later served as a Signaller in the Honourable Artillery Company and survived the war.

The second 17-year-old was Garfield Gustavus Goult. His case was heard in May 1917. Like Robert, he asked for time to finish his exams, which was granted. He later became a 2nd Lieutenant in the Suffolk Regiment. He saw fighting overseas before returning home and becoming an accountant.

A harvested cornfield (K997/56/16)

A harvested cornfield (K997/56/16)

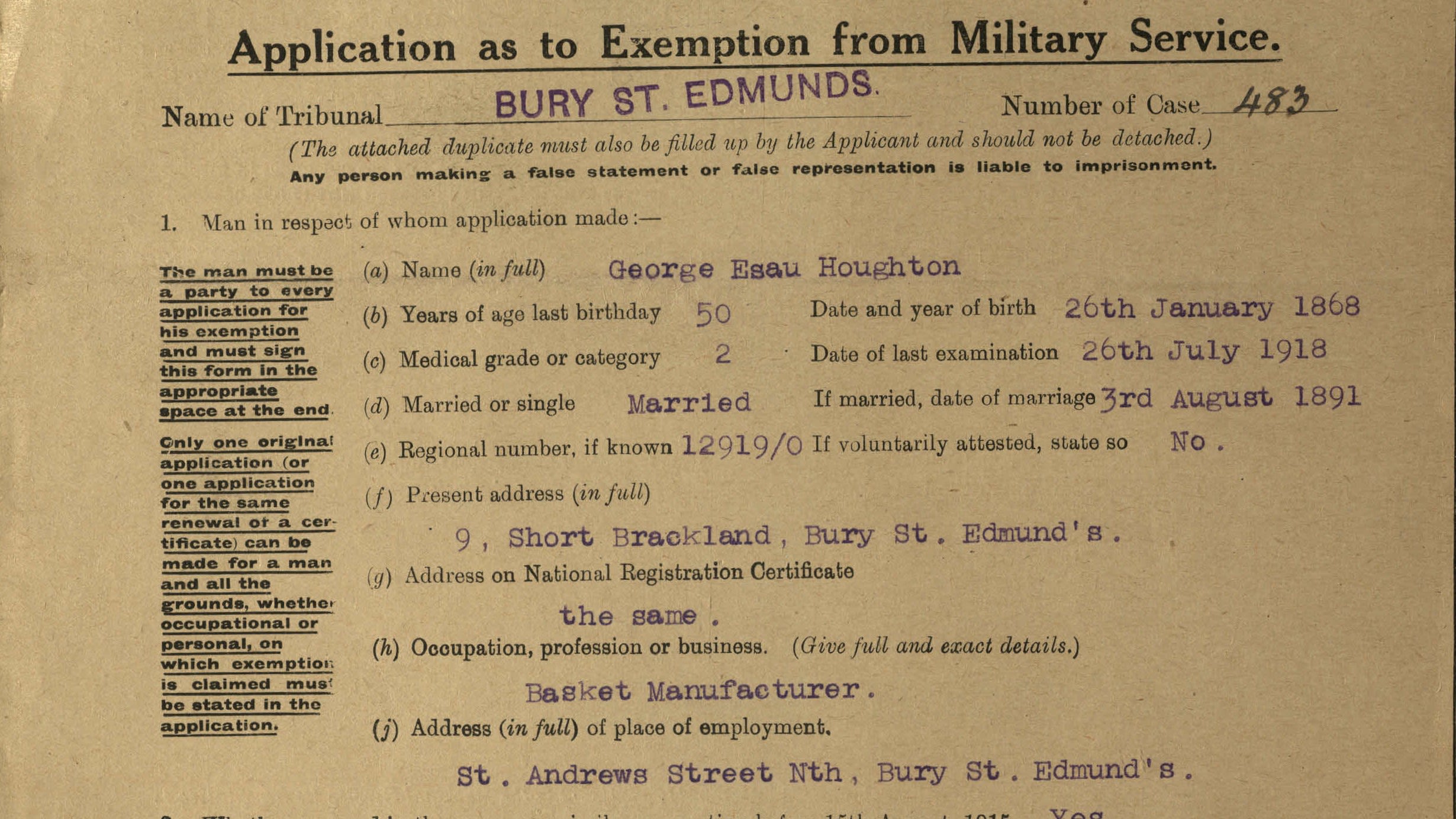

The oldest applicants

The oldest man who applied to the Tribunal was 51-year-old Robert Moore, a brewer’s labourer who worked for Greene King. Seven 50-year-old men applied to the Tribunal, none of whom were actually sent to the army. Some cases were never heard, while others were given temporary exemption which lasted until after the Armistice. If the war had continued much longer some of these men may well have found themselves pressed into service.

Part of the application for George Esau Houghton, aged 50 (EE500/D/12/22/2/483)

Part of the application for George Esau Houghton, aged 50 (EE500/D/12/22/2/483)

Fathers and sons

As the ages of the men being called up increased, so did the chances of men whose sons were already serving being called up. The case of George Hook, aged 38, was heard twice by the Tribunal in the summer of 1916. He was a bricklayer and the applications came from his employer, H.G. Frost, who argued that George’s work on a military camp was of national importance. It was also mentioned that George had five children, one of whom was already in the army, and three brothers serving. On the first application George was granted temporary exemption, but on 29th September 1916 the second application was rejected.

Two weeks later, on 12th October 1916, George’s son, Private Bertram Hook, was killed on the Western Front, serving in the Suffolk Regiment. He was 19.

Shortly after his son’s death, George found himself fighting in France, also for the Suffolk Regiment. He was shot twice and suffered shrapnel wounds and was later interned in Switzerland. He survived the war and returned to Bury St Edmunds.

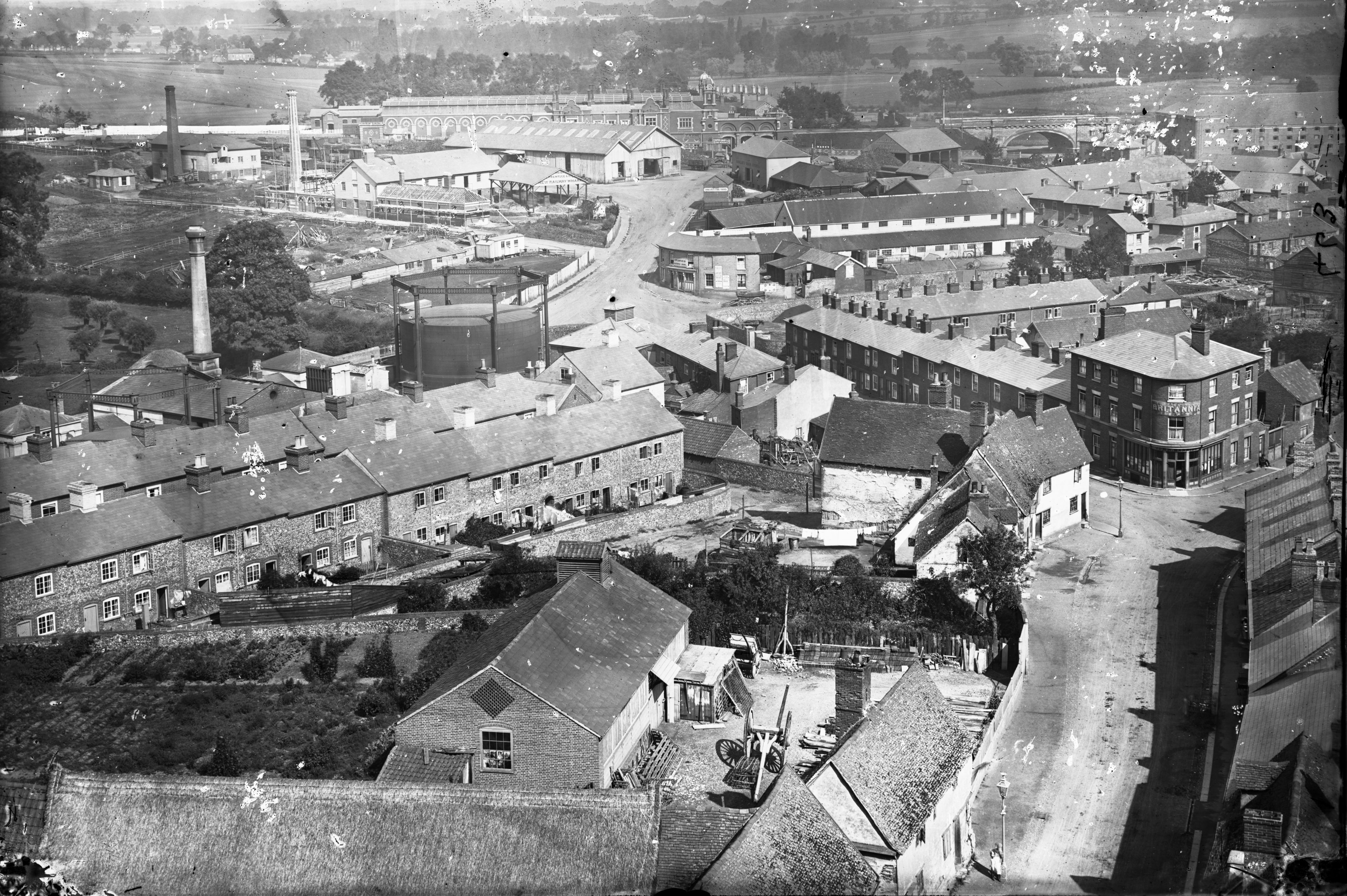

View from St John's church tower, 1871. Peckham Street is the row of houses on the left (K505/1741, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

View from St John's church tower, 1871. Peckham Street is the row of houses on the left (K505/1741, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

Grounds for appeal

The vast majority of applications to the Tribunal argued that it was in the national interest for the man to stay in his usual employment, and/or that military service would cause him or his family serious hardship. A few cases gave reasons of ill-health or disability, and only 5 were made on the grounds of conscientious objection.

One of the hundreds of men who stated that military service would cause severe hardship was Albert Crighton, a Travelling Showman. In spring 1916 Albert applied for absolute exemption, explaining that his wife, Susannah, had just been discharged from St Clement’s mental health hospital after a year-long stay. The couple had three young children, including a baby born while she was in hospital. Albert was worried Susannah would become seriously unwell again were he to be called away.

‘if I had to join up it would involve great hardship… I have no doubt it would so upset her that she would have to go back [to hospital] again’

Researching the family shows that Albert and Susannah had experienced severe hardship in their marriage; they had had seven children, four of whom died.

Albert was granted 6 months of exemption, but went on to apply again, explaining that his wife’s health had not improved. He was, he said, willing to do any sort of war work which would allow him to stay at home. It was also, he argued, ‘absolutely impossible’ for Susannah to look after his two vans and four horses. These were essential for his business and losing them would mean ‘absolute ruin’. His last application in spring 1918 included a doctor’s note which stated that Susannah was suffering from delusions and it was ‘essential that the husband should be constantly with her’.

Perhaps surprisingly, the Tribunal was sympathetic to Albert’s plight. His case was heard five times across two years, with the Military Representative repeatedly objecting to his exemption. He was given a series of temporary exemptions which eventually got him to the end of the war.

Unfortunately, there is a sad twist to the story. Having succeeded in staying with his family throughout the war, Albert was a victim of the flu pandemic which followed it, dying in 1921, aged 42. Records suggest that Susannah died shortly after, leaving the children orphaned after all. They did at least find a home with relatives in Birkenhead, and later worked on a fairground there.

A Crighton's electric roundabout in Stoke-by-Nayland, 1920 (KPF/Stoke-by-Nayland/6)

A Crighton's electric roundabout in Stoke-by-Nayland, 1920 (KPF/Stoke-by-Nayland/6)

Wartime stress

Records from the Tribunal often provide glimpses into what life was like in wartime Bury St Edmunds, including the effects of air raids by Zeppelins.

On the night of 31st March 1916 six people were killed in Bury St Edmunds by a Zeppelin raid (a few more died later of their injuries). Several more people were injured and houses badly damaged.

One of the families affected was the Philpots – parents Arthur, 38, and Catherine, 36, and their two young daughters, Dorothy, 8, and Marjorie, 4, who lived at 6 Springfield Road. Their house was badly damaged by the raid and they moved out temporarily to 7 Nelson Road.

Arthur must have received his call-up papers shortly after the raid, as he filled in an application to the Tribunal on 22nd June 1916. He wrote:

Victim to air raid 31 Mar 1916; Home uninhabitable under repairs; wife and 2 children under medical treatment.

Having asked for total exemption he got the next best thing, a conditional exemption so long as he remained in his current job and joined a wartime voluntary service.

Zeppelin raids were also a major factor in the application of Arthur Garrard. Arthur was 31, and an Assistant Superintendent for Pearl Assurance. He asked for exemption because his wife was severely distressed by the raids.

‘she could not rest or sleep till it gets daylight’

She had gone to stay somewhere out of town but was still experiencing extreme anxiety. An impatient military representative objected to all three of Garrard’s applications for exemption. He was granted temporary exemption three times, before going on to serve in the Queen's (Royal West Surrey) Regiment and Labour Corps.

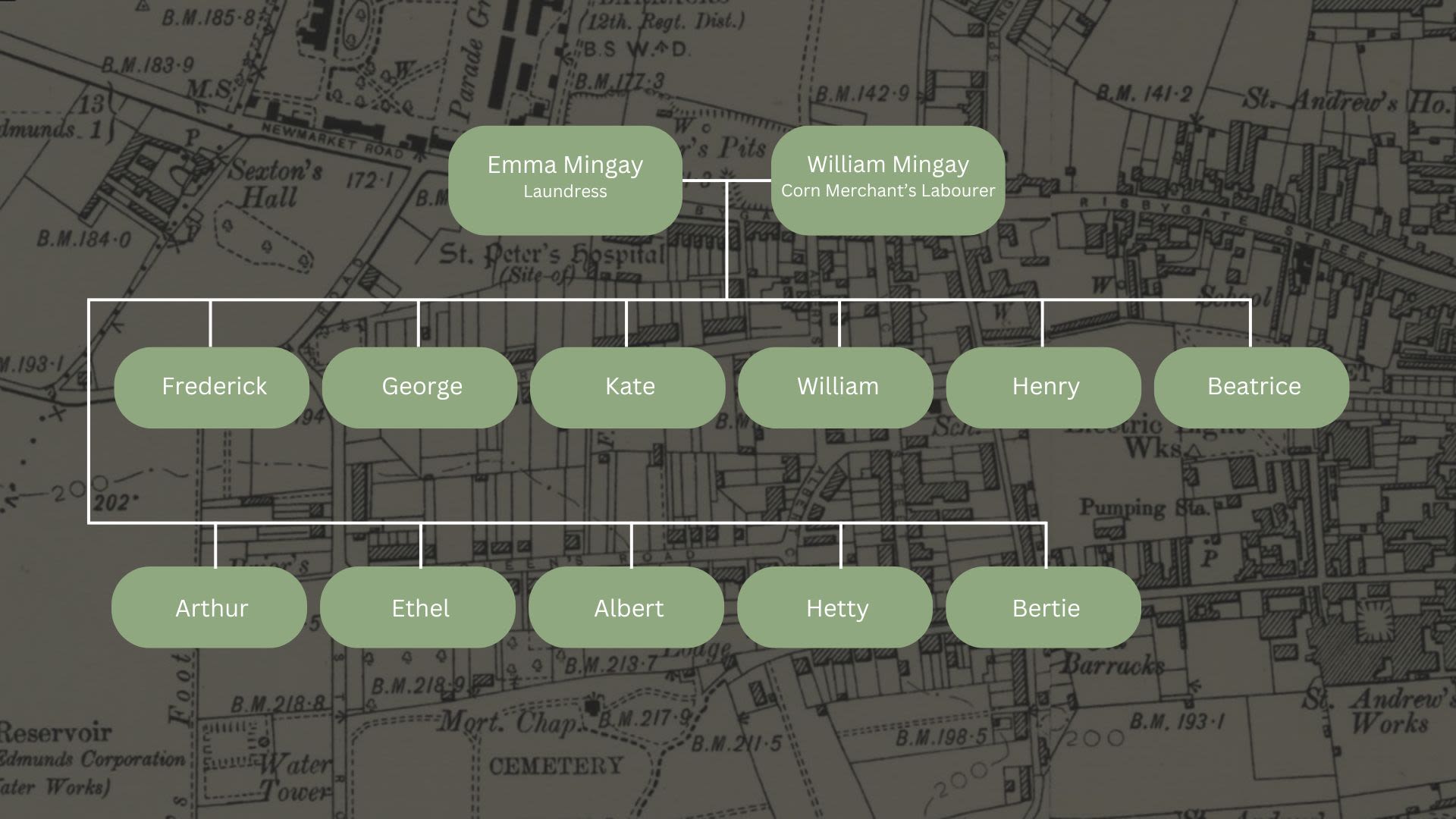

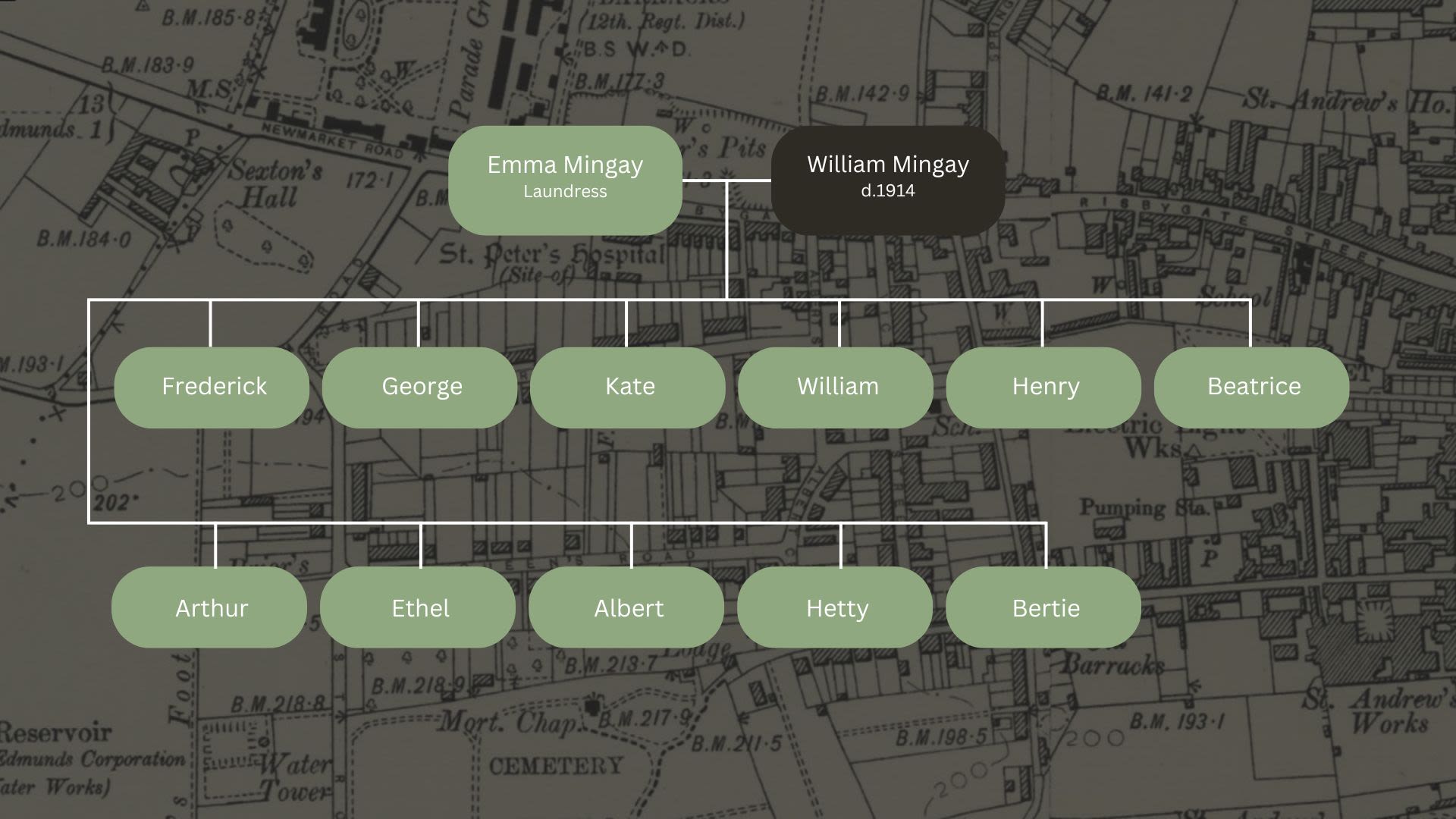

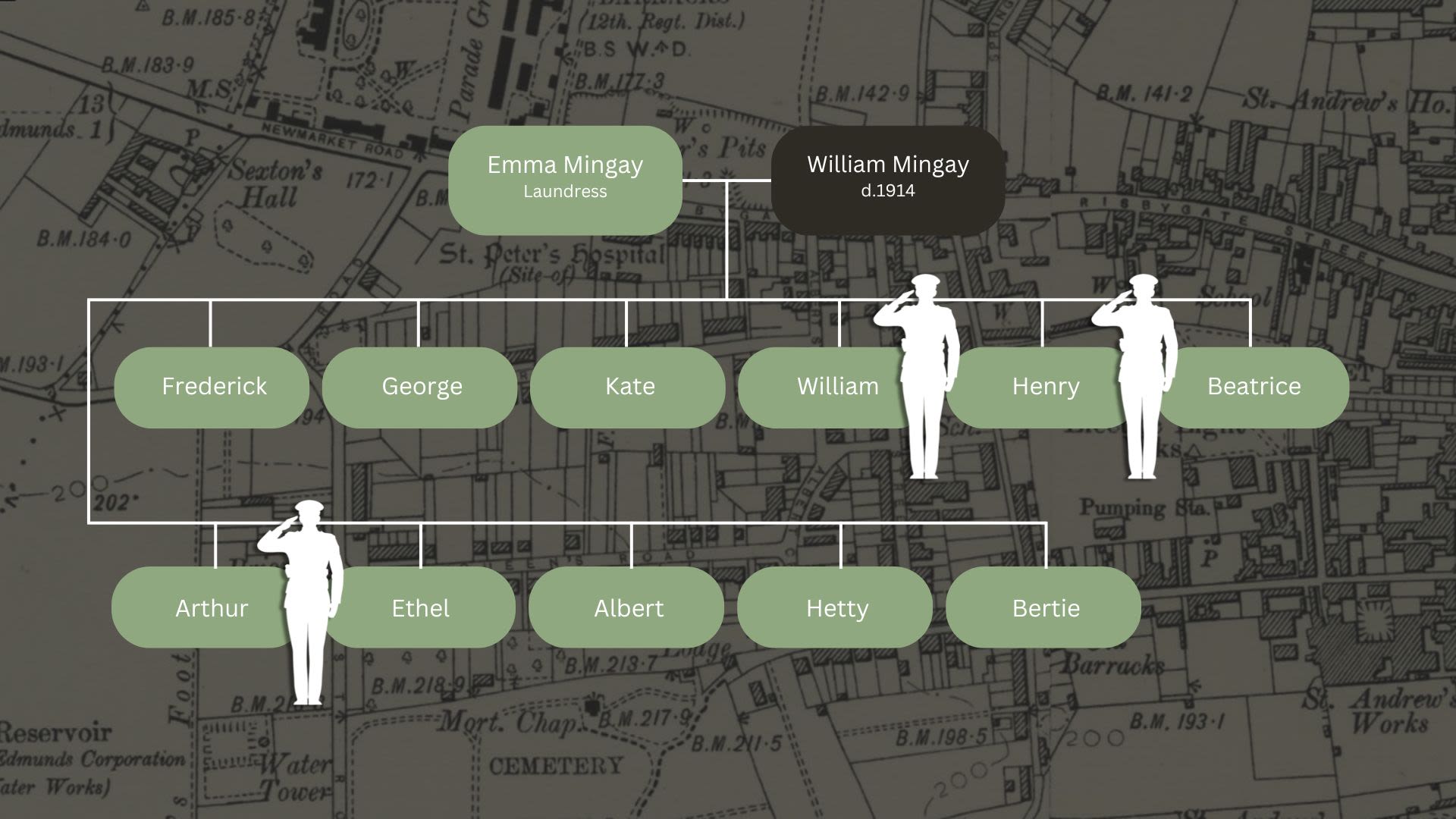

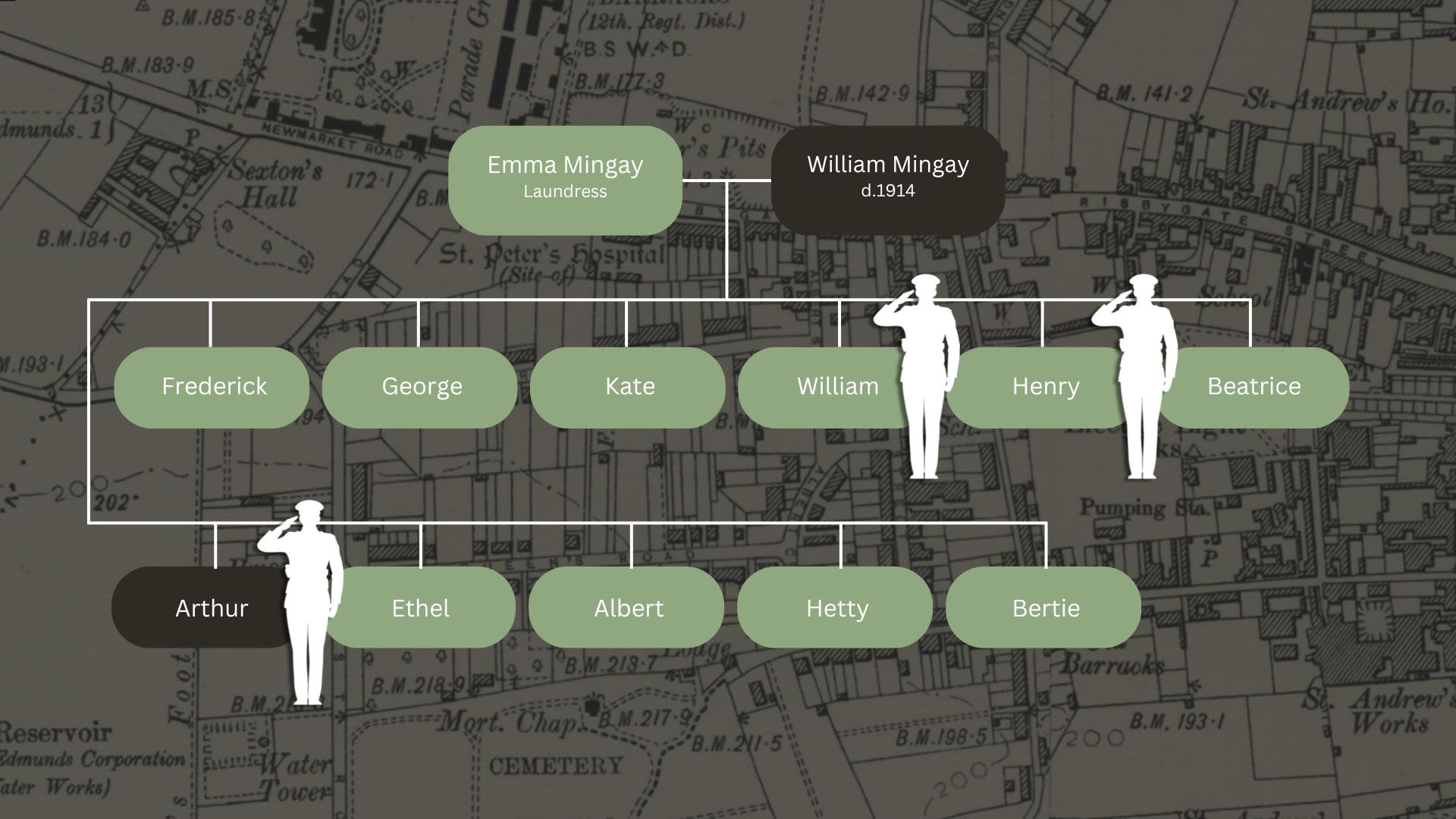

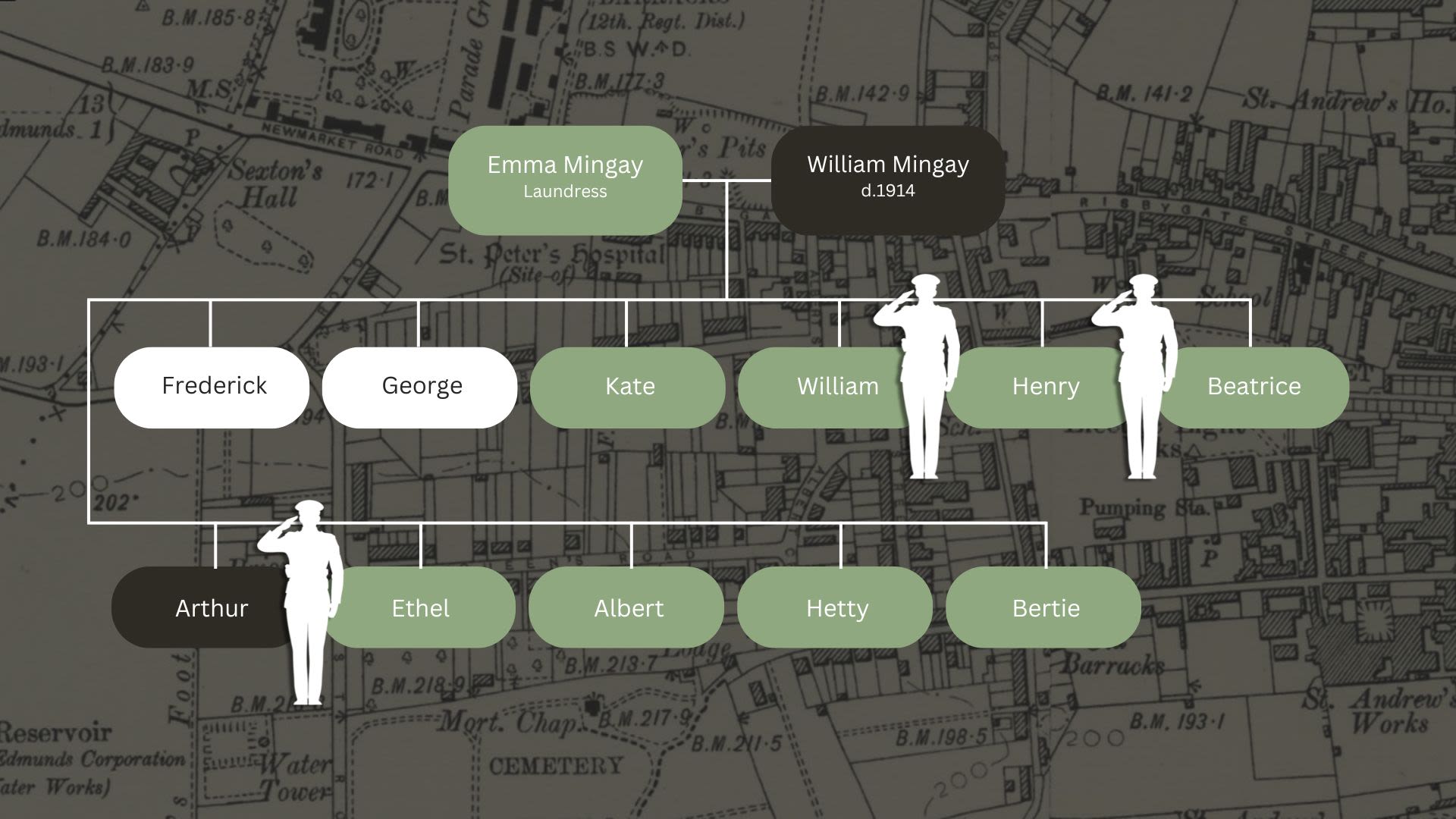

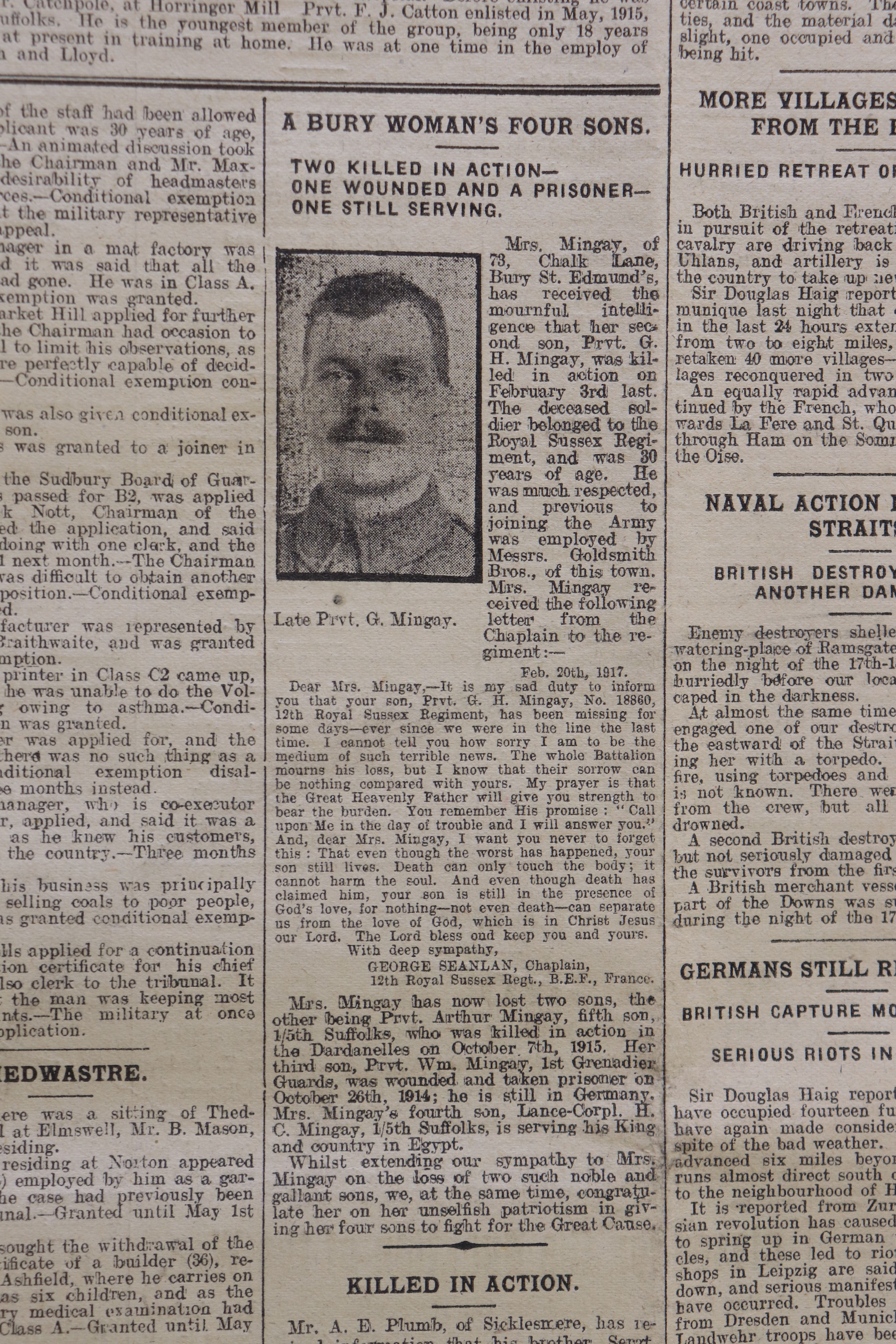

Brothers in the balance - the Mingay family

The Mingays were a working-class family who lived on Chalk Lane in Bury St Edmunds, near the town's electricity works.

Parents Emma, who worked as a laundress, and William, a corn merchant's labourer had 11 surviving children.

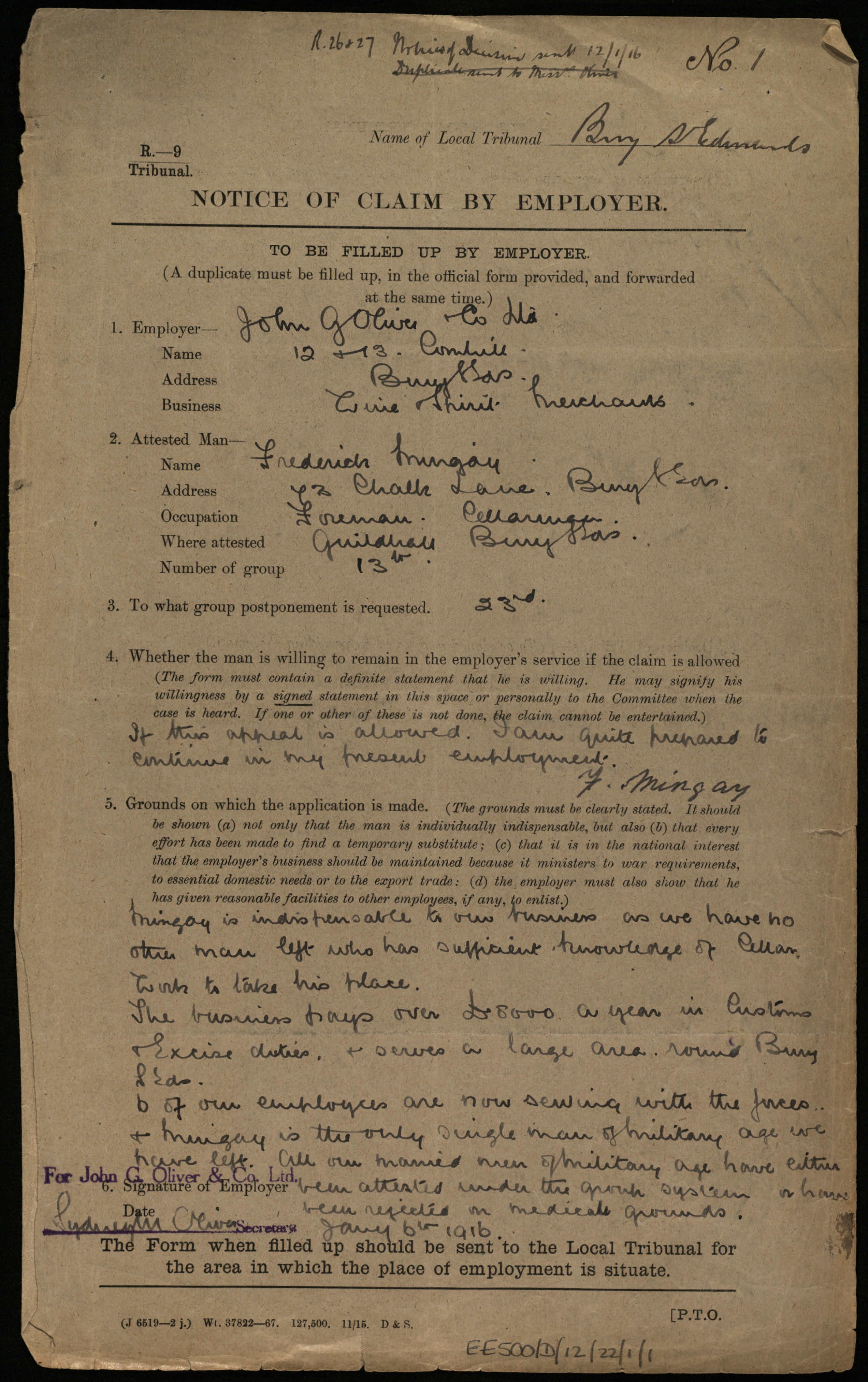

In June 1914, a few weeks before the outbreak of war, William Mingay died aged 51. This left the eldest son, Frederick Mingay, as the family's main wage earner. He was head cellarman for John G. Oliver, a wine merchant and also a Tribunal panellist.

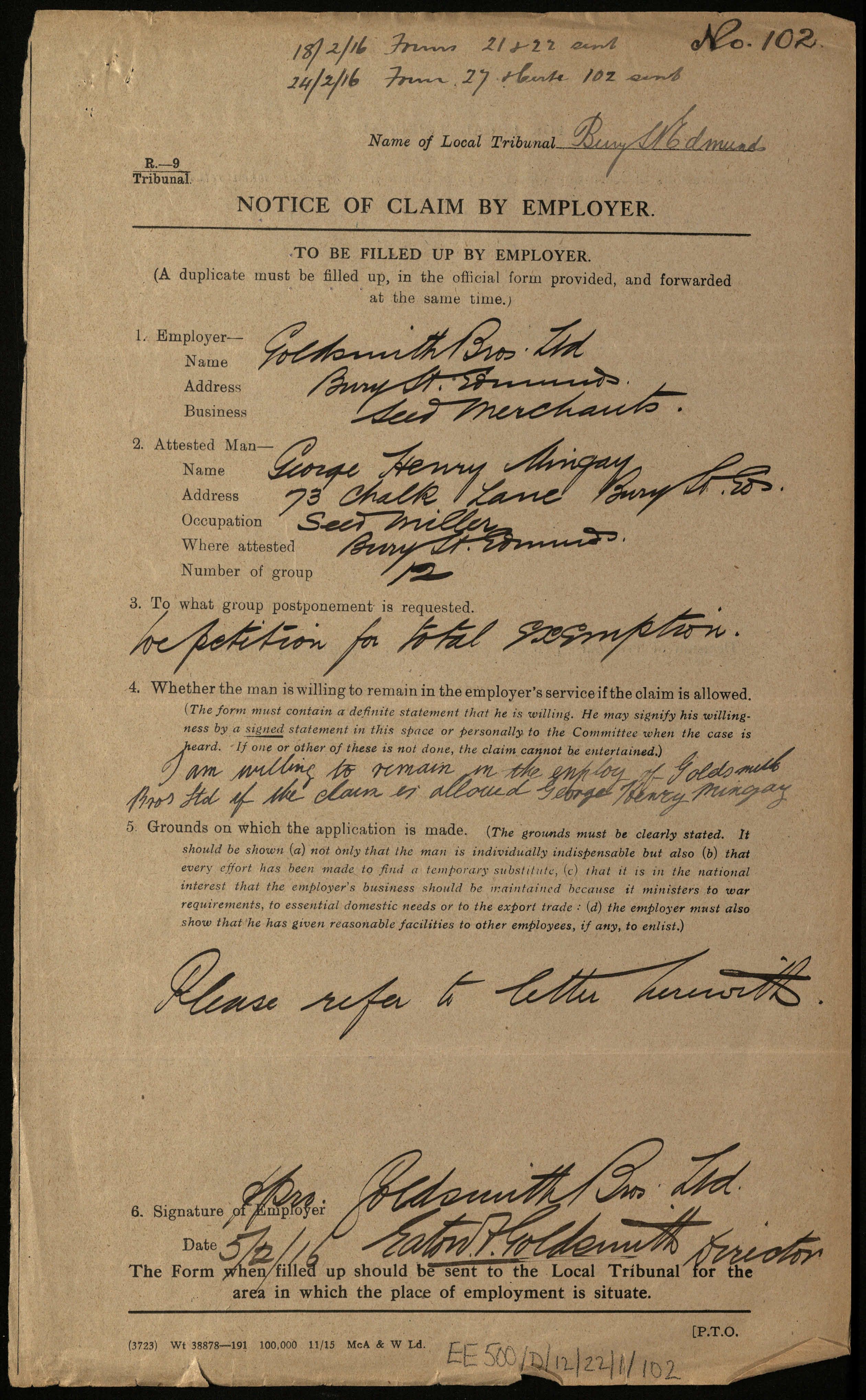

The family's second son, George, worked for Goldsmith Brothers Ltd as a seed miller, a job he had taken over when his father died.

Kate and Beatrice, like their mother, worked as laundresses. The four youngest children were still at school.

Emma's third son, William, was already serving in the Army before the war with the 1st Battalion of the Grenadier Guards. He was wounded and reported missing in December 1914. He was confirmed to be a prisoner of war in April 1915, and held until 1919.

Her fourth and fifth sons, Henry and Arthur, volunteered for military service with the Suffolk Regiment during the first years of the war.

In the early hours of 7th October 1915 Arthur was killed in Gallipoli, aged 19.

Frederick and George were due to be mobilised in February 1916. If both joined the army Emma would be left with several dependant children and no principal wage earner.

In January 1916 Frederick's employer, John G. Oliver, applied for his military service to be delayed until March. Oliver argued that Frederick's experience and knowledge were 'indispensable to the business'.

This was the very first case that the Tribunal heard.

Frederick was granted temporary exemption to the end of March.

Goldsmith Brothers Ltd then made an application for absolute exemption from military service for George Mingay. They stated that his job was a very responsible one which required practical experience and there was no-one who could replace him.

The Tribunal granted George temporary exemption until the end of April 1916.

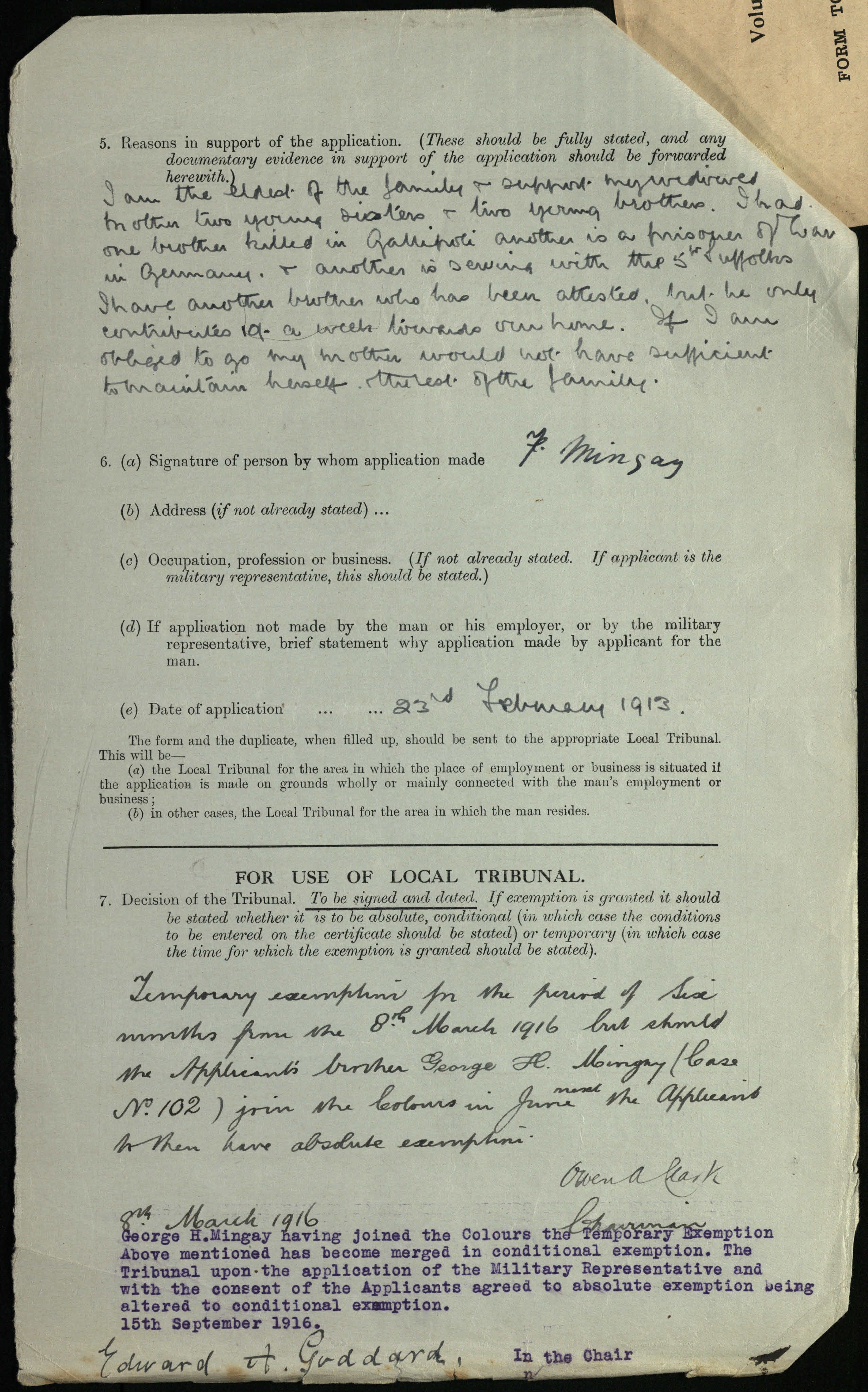

John G. Oliver then made a further application in February 1916, this time for absolute exemption from military service for Frederick. Frederick also made a personal application for exemption, stressing his role as provider for his mother and dependent siblings, and arguing that if he was called up, they would not have sufficient means to maintain themselves.

The Tribunal ruled that Frederick be granted “temporary exemption for a period of six months from 8 March 1916 but should the Applicant’s brother George H. Mingay join the colours in June next the Applicant to have absolute exemption.”

Their decision was that one of the two brothers would have to fight.

A few weeks later, George joined up.

George served with the 12th Battalion (39th Division) of the Royal Sussex Regiment. He was killed in action on 3 February 1917, on the Ypres Salient.

The chaplain of his regiment wrote to Emma to inform her of her son's death.

Emma's other two serving sons, William and Henry, both returned home. William, however, died in 1924, aged 34, leaving a widow and three children.

Henry Oswald Ashton, courtesy of Rob Ashton

Henry Oswald Ashton, courtesy of Rob Ashton

Henry Oswald Ashton

Henry Oswald Ashton was the son of Henry Bankes Ashton, a solicitor and one of the original members of the Tribunal. Henry Oswald Ashton was also a solicitor and a partner in his father’s firm.

He acted as legal representative for a number of men at the Military Tribunals in Bury St Edmunds. He was instrumental in helping them to obtain temporary and conditional exemptions in several cases.

Newspaper reports describe Henry as an exceptional young man, a keen athlete and a prominent member of Bury society.

Henry had held a commission in the Suffolk Territorials that he had resigned prior to the outbreak of war. He did not join the army on the outbreak of war as so many other staff had left his father’s firm and he was needed there.

He was called up for military service in early 1916 and applied to the Bury St Edmunds Tribunal for a temporary exemption on hardship grounds.

‘I am ready and willing to serve provided I can find someone to do my work and assist my Father and I ask that I may be allowed a period in which to endeavour to obtain such assistance’

His case was heard on 27th March 1916 and he was granted exemption until 1st August 1916.

Henry went on to serve in the Suffolk Regiment and then the Royal Warwickshire Regiment.

He was killed in action on the Western Front near Bapaume on 29th August 1918. He was 28 years old and left a widow and 3-year-old son.

Brewers, bakers and innkeepers – the impact of the war on working life

As well as insights into personal lives, the Tribunal records also tell us about the working life of Bury St Edmunds. The largest sector was retail, followed by agriculture and engineering.

Greene King – a skeleton staff of inexperienced hands

Brewing also features prominently. 35 men from just one employer, Greene King, were seen by the Tribunal, some of them more than once.

The appeal papers make it clear that the brewery was extremely short staffed by March 1916. For example:

- George Sparrow was the only engine driver and stoker left. As he was in charge of the boilers, coppers, and engines, it would be a safety risk to replace him with anyone less experienced.

- In the bottling stores, there were 30 boys under one foreman, William Loader. All his men had been called up.

- Edward Fulcher Carliell, a highly qualified brewer, argued that his expertise was needed in No. 2 brewery as 49 men had gone and only old men and boys were left, plus some attested married men who were likely to be called up at any time.

- Horse-keeper, Walter Bays, was in charge of the brewery’s 27 horses.

Most of these men were granted temporary or conditional exemption, with the Military Representative often in disagreement.

From horses to lorries

The importance of motor transport is central to many Greene King Tribunal cases. In 1913 the brewery had 59 horses, which were gradually being replaced by motor lorries. It became vital for Greene King to hold on to its motor drivers and mechanics.

In June 1916 an appeal was made for five Greene King lorry drivers. The outcome was a compromise: two men must serve in the military while three men, including the chief motor engineer Edwin Drury, must stay working for the brewery. It was recognised that well-maintained lorries and their drivers were not only essential for Greene King’s business, they helped the war effort by keeping traffic off railway lines and by doing emergency work. The Military Representative went along with the decision but on an undertaking from the firm that it would not make any further appeals for their workers.

Edwin Drury had already been to the Western Front and had recently returned sick. He had worked for the British Ambulance Committee with the Section Sanitaire Anglaise – an independent body set up by wealthy subscribers to provide motorised transport for wounded French soldiers. His appeal papers state that he had been mentioned in despatches by French military authorities for this work.

Despite the fact that Drury had lost an eye in an industrial accident, the Military Representative was still keen for him to enlist and challenged his exemption twice. At the second of these hearings, Greene King’s Managing Director explained that Drury was ‘the only man they had left possessed of any mechanical knowledge. With a valuable stock of motors and motor lorries representing many thousands of pounds’, he was essential if they were to be kept on the road. They would also not be able to release brewery horses for government service if they could not use their motor lorries. Drury did not see active service again.

Drury stayed with Greene King for the rest of his working life. By 1924 there were only ten horses left, the rest having been replaced by eighteen lorries and vans.

Greene King motor vehicles (courtesy of Grene King)

Greene King motor vehicles (courtesy of Grene King)

A British Ambulance Committee vehicle in France (Imperial War Museum)

A British Ambulance Committee vehicle in France (Imperial War Museum)

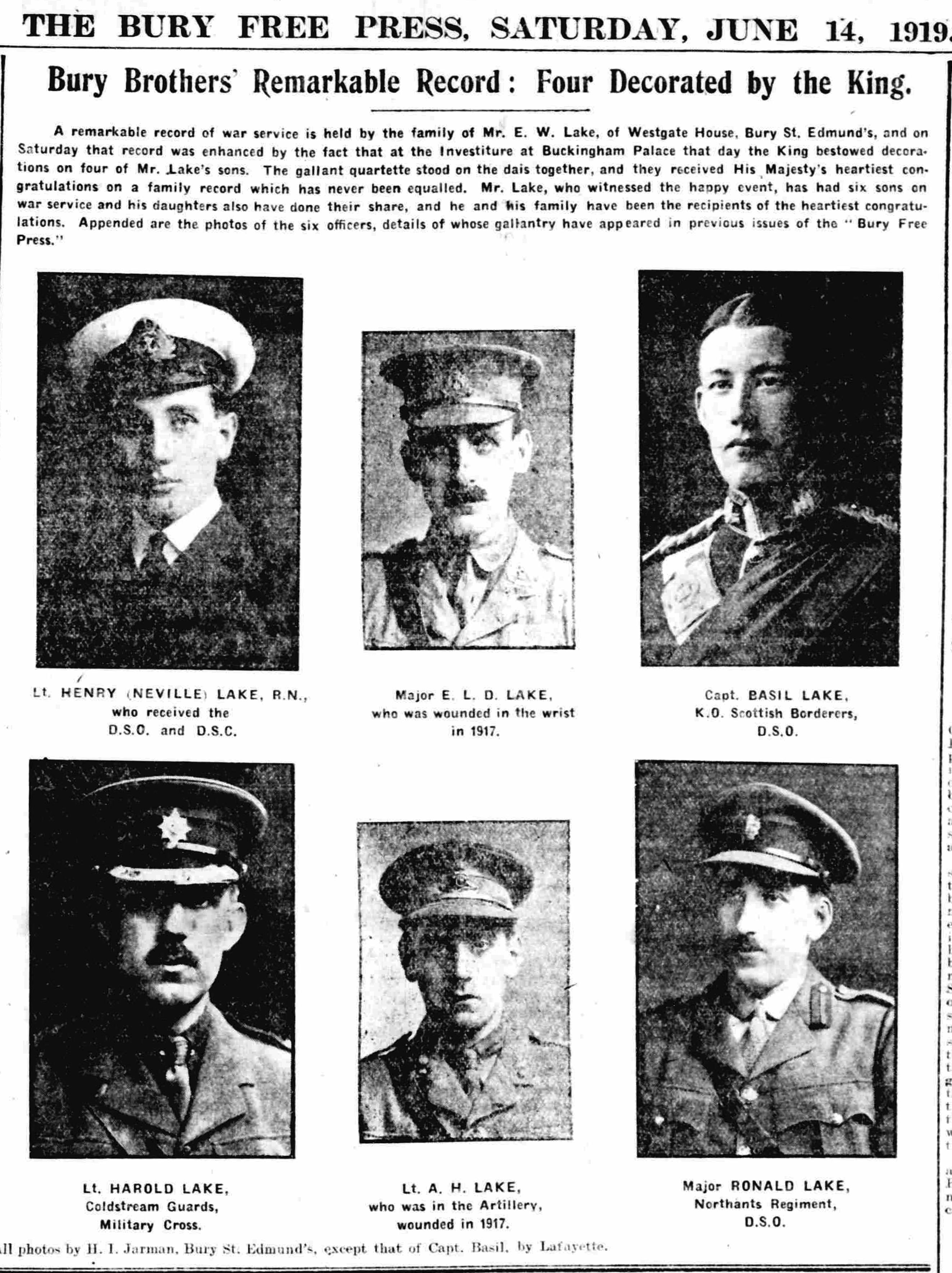

Keeping the business going

One of Greene King’s senior executives, Harold Lake (1882 – 1960) had the responsibility of keeping the business going. Lake and his family were at the heart of Bury society – Conservative Party stalwarts, active Anglicans, Freemasons and enthusiastic amateur thespians – similar in interests and social standing to many of the Tribunal panellists. He was the fifth child (and second son) in the large family of thirteen children born to Blanche Lake and her husband Edward who was Managing Director of Greene King.

The Lake family (K505/3381, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

The Lake family (K505/3381, courtesy of Bury Past and Present Society)

By the time of his first appeal on 21 January 1916, Lake, a solicitor by profession, was one of the brewery’s most senior managers. The company appealed for a temporary exemption for him, asking his call-up to be delayed for as long as possible. It argued that it was ‘impossible to find anyone with sufficient knowledge to do this work and every eligible man having already joined’.

On the same day, Lake also applied on his own behalf. He argued that his significant family responsibilities warranted an absolute exemption. He had five brothers already serving. Two of them had been brewery managers. Lake was fulfilling their duties at work as well as his own. He also had five unmarried sisters and therefore argued that ‘my responsibilities are greater than most married men’.

The outcome of these two hearings was that he was refused absolute exemption but allowed to defer his call-up to March/April 1916.

In March 1916, Greene King applied again for Lake, arguing this time for absolute exemption. To support this, the company reasoned that because one of his duties was to manage the Stowmarket waterworks he was in a certified occupation. His family and business responsibilities were cited as before.

Although Lake successfully got an absolute exemption this time, he did in fact join the Army. The circumstances are unknown. Already an officer in the Suffolk Volunteer Regiment, he joined the Coldstream Guards as a Second Lieutenant in January 1917. Serving in France, he was wounded later that year, promoted, and awarded the Military Cross.

After the war, he returned to his former occupation. He became a member of West Suffolk County Council in 1920 and a Director of Greene King in 1922.

All six Lake brothers survived the war, with four being awarded gallantry medals.

The mixed wartime fortunes of Bury's publicans

In addition to brewing, pubs were also an important part of working and social life in Bury St Edmunds.

Eighteen Bury publicans applied for exemption from military service. They often argued that leaving the businesses they had built up over many years would cause serious hardship. Some told the Tribunal about wives who were pregnant or other dependants who would not be able to manage the business on their own. Others highlighted the value of their work to the local community, including food production, billeting for soldiers, and their voluntary war work.

The Military Representatives argued that public houses were not necessary businesses in wartime.

Forty-year-old Frank Dutton was the licensee of the King of Prussia on Southgate Street. After the outbreak of war, passing troops would throw stones at the pub sign. It was patriotically renamed the Lord Kitchener in 1914.

The Lord Kitchener was badly damaged in a Zeppelin raid on 31 March 1916.

Frank was granted exemption conditional upon undertaking voluntary war work in June 1916. The Military Representative unsuccessfully tried to have this exemption overturned in January 1917.

Thirty-three-year-old Henry Arthur Orbell Fenner ran the Saracen's Head on Guildhall Street. When he applied for exemption, the Military Representative argued that Fenner's wife could take over the business; they were often more prepared to suggest women take over traditionally male roles than employers were.

Fenner was granted temporary exemption for a month and his wife Eva took over the business. He went on to serve as a bombardier with the Royal Field Artillery.

The outcome was taken as precedent for later cases involving publicans. The licence holders of The Saracen's Head, the Dog and Partridge, the Royal Oak, the Red Lion, the St Edmunds Head and the Plough applied for the licenses to be transferred to their wives when they left to join the military in 1917.

Thirty-eight-year-old George Victor Barrett ran the Dog and Partridge on Crown Street.

His application for exemption from military service was supported by a petition signed by his regulars and residents of Crown Street, praising the well-run house and “good class of the trade”.

The Tribunal panel looked favourably upon his case, stating beer was "a national drink" and "a national revenue comes from it".

The Military Representative, however, was not in agreement:

"The nation requires his service more than this street"

Despite the local support, Barrett's temporary exemption was withdrawn on 31 December 1916.

Of the eighteen publicans who applied for exemption, only those over forty years of age who demonstrated additional benefit to the community and undertook voluntary war work were exempted from military service.

Dozens of bakers

Food production was also a big part of Bury’s economy. One significant part of that was baking, with 58 applications concerning men who worked for bakeries.

Some of these provide detailed insights into these men’s working lives. William Sapey, who worked in a bakery on Raingate Street, wrote that he worked 12 hours a day, baking 6,000 loaves a week. The Co-operative Society applied for exemption for Percy Bouttell, who baked for the military as well as local residents. If he were taken, they argued, there would be ‘hardship amongst the working class of Bury’.

Applications from bakers sometimes prompted fierce debate. At a case about a baker at the West Suffolk Appeal Tribunal one of the panellists gave a blistering view:

‘Mr. Hustler said it would be a good thing if all the bakers’ shops in the country were shut up. The poor would save in money and flour if they baked their own bread. People were too lazy to bake; that was what it was.’

This perspective does not seem to have been widely shared, and the Bury Tribunal usually granted some sort of exemption to bakers. Of the Bury bakers who were not exempted only 3 ended up serving, one of whom, Frank Clegg, a master baker for a business in Risbygate Street, was killed.

Looking at the numbers of bakeries in Bury St Edmunds over time we can see whether the war had much impact on the trade. Trade directories show that there were 28 bakeries in Bury in 1912, 27 in 1916, and 24 in 1922. This was the beginning of a slow decline in the number of bakeries; by 1937 there were only 17. Likewise, the number of people working for bakeries seems to have gone down over time. In the 1911 census 116 people in Bury can be identified as working for bakeries. In 1921 there were 99, and in 1939 there were 60.

The decline during and after the war years is likely part of wider trends. Businesses had to find ways of working with fewer employees during the war, but also benefitted from technological developments. For bakeries, this meant more efficient baking with gas ovens, and motor transport which enabled them to deliver across a wider area. The economy which surviving soldiers returned to would not have been quite the same as the one that they left.

Delivery cart for A.J. Manning of West End Bakery (K772)

Delivery cart for A.J. Manning of West End Bakery (K772)

Motor van for Westgate & Sons bakers (K1174/6)

Motor van for Westgate & Sons bakers (K1174/6)

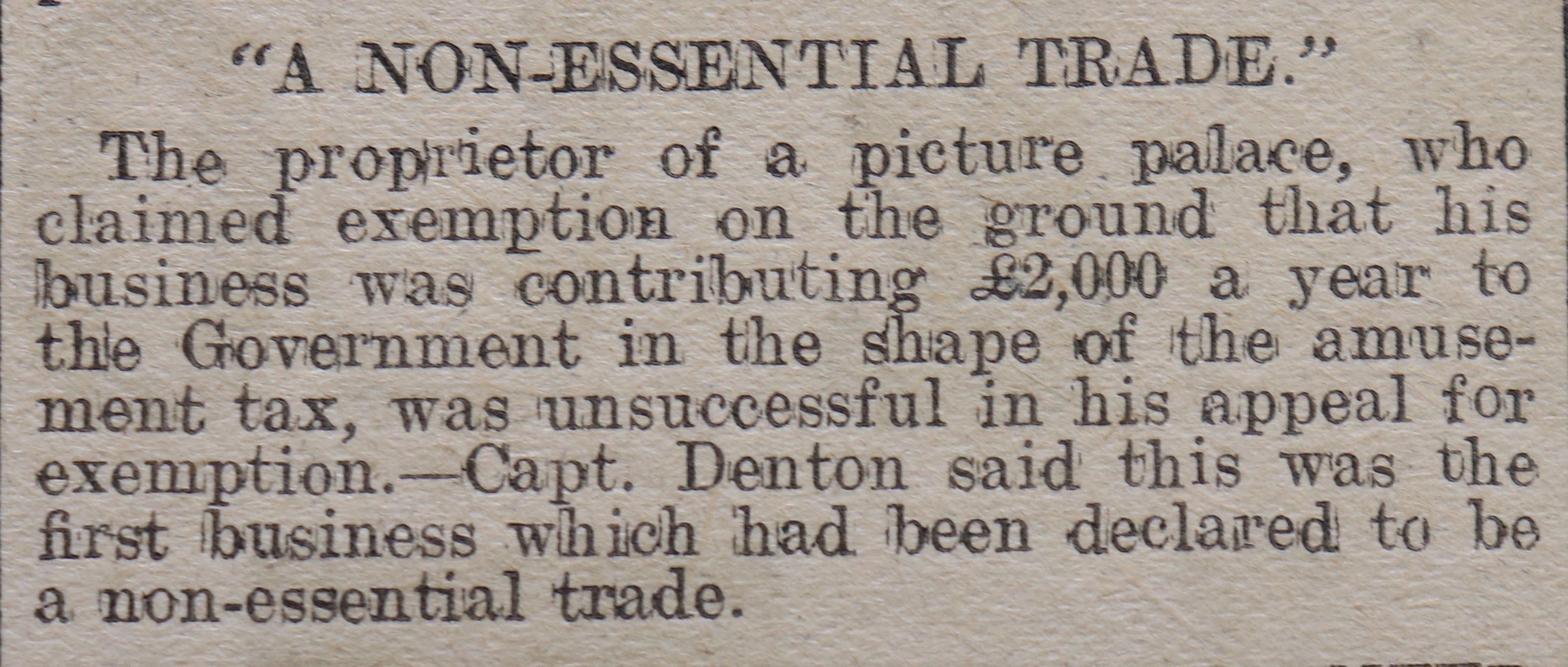

‘A non-essential trade’?

Applications to the Tribunal often sparked discussions about whether a man's occupation was essential or not.

Sidney E. Frank, 34 years old and originally from Hackney, lived at 69 Guildhall Street. He was proprietor and cinematographer of the Empire Electric Palace cinema on the Cornhill.

The cinema had first opened in 1911. It was built behind the Post Office, and was reached through Bell's Arcade, which ran between the Post Office and a Lipton's shop. Initially it could seat 300, but within a year the capacity was increased to 450.

Frank first appeared before the Tribunal on 20th October 1916, having applied on his own behalf for exemption from military service. He argued that money was required to pay for the war as well as men. He stated that he paid about £40 to the Government each week in entertainment tax. He added that should he have to serve, he would have to close his business that had taken twelve years to build up. Frank’s persuasive argument led to him being granted conditional exemption so long as he remained in the same work.

However, the Military Representative successfully sought to have Frank’s conditional exemption withdrawn in January 1917. Frank appealed the decision but this was dismissed on 22nd February 1917. According to Captain Denton in the Bury Free Press on Saturday 24th February 1917, this was the first example of a Bury business being declared to be a non-essential trade.

Bury Free Press, 14th Feburary 1917

Bury Free Press, 14th Feburary 1917

Sidney’s case was perhaps heard in the light of an earlier case of another Bury cinematographer in March 1916. W. Cook applied for his employee, Charles Woodward, a cinematograph operator. Cook argued that he could not run the business without Charles, and ‘it would be a national calamity to close picture palaces at the present time’ (Bury Free Press, Saturday 25th March 1916).

He was laughed at, but continued to say that cinema had ‘contributed greatly to the benefit of the public’. The Military Representative disagreed, and said that cinemas provided amusement but were not essential.

‘the occupation of a cinematograph operator was not a necessary one and a young man 28 years of age ought not to be employed in amusing people instead of going to the war’.

Both Sidney and Charles went on to serve in the army, Sidney as a Gunner with the Royal Garrison Artillery and Charles in the Labour Corps. Both survived and returned to Bury St Edmunds.

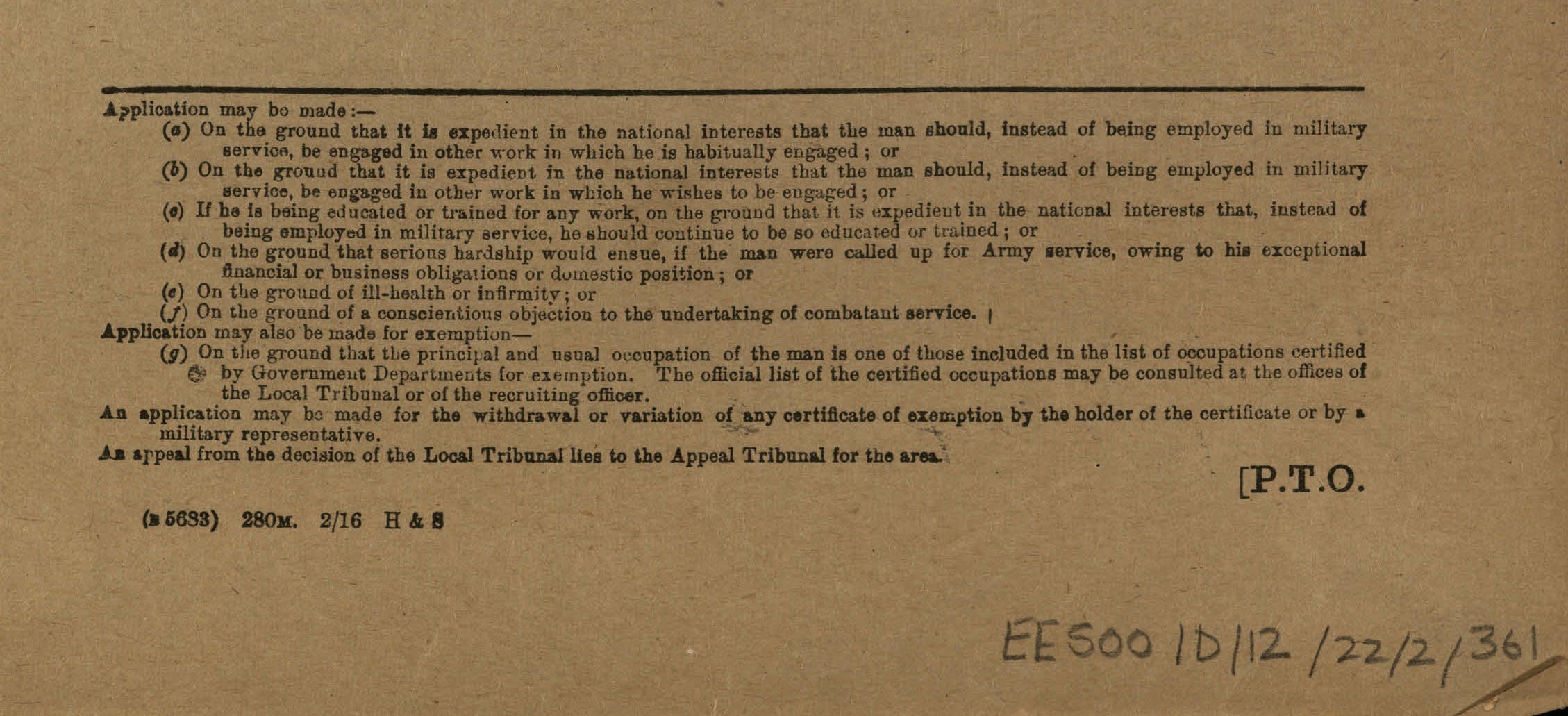

The grounds on which non-attested men could apply for exemption (EE500/D/12/22/2/361)

The grounds on which non-attested men could apply for exemption (EE500/D/12/22/2/361)

Conscientious Objection

Non-attested men could apply for exemption from military service on the grounds of Conscientious Objection. Some asked for exemption from combatant service only, others for total exemption from anything related to the war.

Only five cases of Conscientious Objection have been found among the Bury records - about 1% of the Non-attested cases. This is about half the national average which has been estimated at 2%. It is possible, however, that there were more cases for which the papers have not survived.

The five known Conscientious Objectors were a grocer's assistant, an outfitter's assistant, an apprentice watchmaker/jeweller, and two teachers. All appealed based on their Christian convictions.

Several applied on health grounds as well as conscience grounds. In those cases exemption was granted based on physical unfitness to serve.

Thomas Hunt - an administrative nightmare

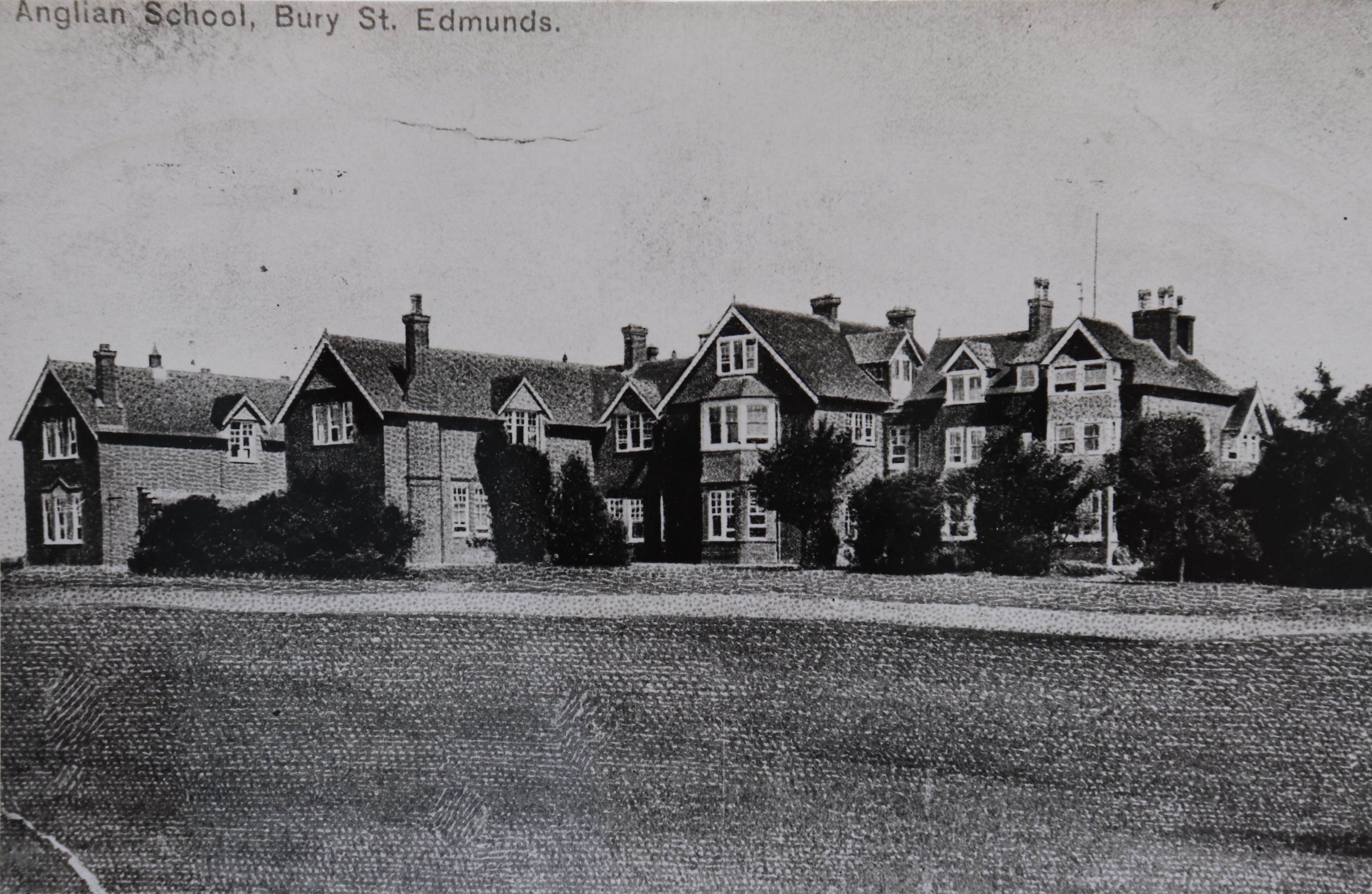

One of the men who applied for exemption on the grounds of Conscientious Objection was Thomas Hunt, a teacher at the East Anglian School on Northgate Street and a Primitive Methodist.

His application for absolute exemption was denied. He appealed, and lost, and was ordered to join the Non-Combatant Corps at Aldershot. He refused to go but was fined and sent off with a military escort.

Somehow the army then lost track of him and police were despatched to search for him in Bury where he was found at home. He protested he had been discharged from the army, but he was charged with desertion and returned to his unit.

On being returned to the army, he was almost immediately hospitalised with complex medical issues. He had been telling the truth - the army had indeed discharged him on medical grounds. Slow bureaucracy and missing papers had caused him to be charged as a deserter by mistake.

The end of conscription

The Bury St Edmunds Tribunal met for the last time on 30th October 1918. The call up of men under the Military Service Acts ceased at midday on 11 November 1918.

Over the two years the Tribunal existed, there were 1,210 applications made to it. 72% of men or employers who applied were given some sort of exemption, although this might have only been for a few weeks.

After the war the government ordered that Tribunal records should be destroyed. Only records from the Central Tribunal and Appeal Tribunals in Middlesex and Lothian and Peebles were kept. It is thought that this was because of the sensitive nature of the records.

Despite this, fragmentary evidence survives in archives around the country. The Bury St Edmunds Tribunal records are rare even among these survivors since the original applications have been kept as well as a register of cases.

Access the records

All 1,210 applications to the Bury St Edmunds Military Tribunal have now been individually numbered. A catalogue detailing the names, ages, occupations, employers, and addresses of applicants is now on the Suffolk Archives website.

Search the records by entering the first part of the catalogue reference number followed by an asterisk, EE500/D/12/22*, then any key words you are searching for, such as personal names, street names, or company names.

You can book an appointment to view original records or order digital copies. Please contact us on archives@suffolk.gov.uk for further information.

The records are now easier to search than ever before and have much still to tell us about the people of Bury St Edmunds during an extraordinary period of history.

Acknowledgements

The cataloguing of the Bury St Edmunds Tribunal records and the creation of this display has only been possible thanks to a dedicated group of volunteers who have put in over 500 hours of work to this project. Suffolk Archives is very grateful to them for their efforts.